CONTENTS

A Word on the Organization of the Book as Four Volumes

Volume Three: The 1907 New Course and Four of Its Players

Where was the New Course of 1907 laid out?

The Scorecard of the 1907 New Course

Clarence M. Warner and Willie Campbell

Can We Identify a Pro Who Might Have Designed the New Course?

Reiffenstein’s Amateur Course Record

The Story of Caroline Herrington

The Story of Thomas D’Arcy Sneath, Part One

The Story of Henry Lovell, Part One

The Story of George Patten Reiffenstein, Part One

New Course of 1907: six-hole and ten-hole rounds?

Foursome Sneath, Lovell, Reiffenstein, and Herrington’s Final Scores

The Story of Thomas D’Arcy Sneath, Part Two: He Shall Never Grow Old

The Story of Henry Peirce Lovell, Part Two: The Horror! The Horror!

The Story of George Patten Reiffenstein, Part Two: What’s in a Name?

The Story of George Patten Carr: More Sinned against than Sinning

The Story of Caroline Mary Sneath and Other Magnificent Herringtons

Foreword

This book remains a work in progress.

I circulated the first edition among members, friends, and supporters of the Napanee Golf and Country Club. I did so first and foremost because it is about something we all love: the Napanee golf course.

But I also wanted to invite people who read this book and find the subject interesting to ask themselves whether they might have a piece of information about the Napanee golf course – a fact, an anecdote, a rumour, a photograph of some part of the golf course, an old publication from the club, or even an old scorecard--that they could pass along to me. Information about the golf course that lies in the background of a photograph, for instance, even if it is only a photograph of a trophy presentation or of a group of friends playing golf, or information that emerges from a story about the past, may help to fill out the picture of the history of the design of the golf course that I sketch below.

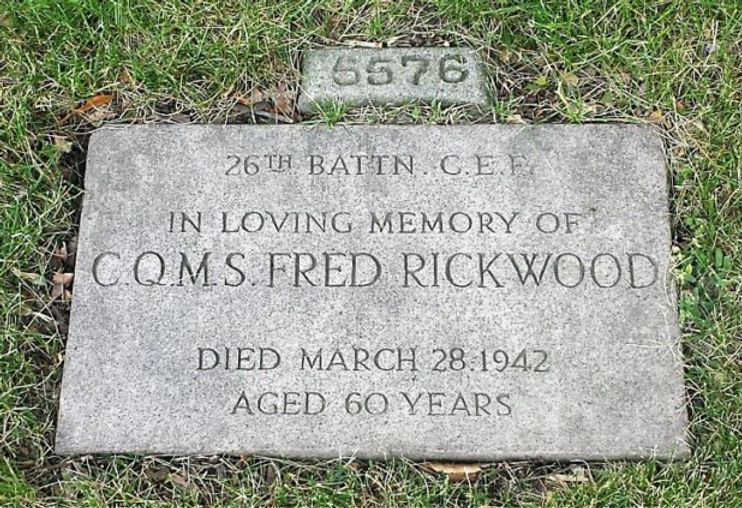

The second edition of Volume One is archived at the Orillia Public Library. So I similarly invite anyone from Orillia (where Fred Rickwood concluded his career as a golf professional in the early 1940s) who might have information about him to pass it along to me. People able and willing to share a memory of him will contribute to the remembering that he deserves.

Feel free to email me: dchilds@uottawa.ca

More information about either the Napanee golf course or the man who designed it will make for a better third edition.

Donald J. Childs

Acknowledgements

My brother Bob Childs has done wonders with computer technology on my behalf, especially with regard to old photographs. His love of Napanee Golf and Country Club probably exceeds my own, and it certainly inspired me in my work on this book.

Milt Rose’s enthusiasm for the history of the golf course, particularly as shown by his willingness to listen to my recitation of facts and figures that emerged as I first worked on this book, was also an encouragement to me.

Napanee Golf and Country Club’s Golf Course Superintendent Paul Wilson has generously provided me with helpful information that he has gathered from his work on the course over the years.

I appreciated Rick Gerow’s willingness to tell me about the construction of various parts of the golf course in the 1980s and 1990s, even though we were playing golf at the time and he was in the process of winning the Super Senior Golf Championship.

Similarly, Bing Sanford cheerfully and helpfully identified features of the Rickwood course for me when we played a round of golf together. It was always a pleasure to be in his company.

Mike Stockfish read an early draft of the book and offered encouragement and useful advice, for which I thank him.

When I requested information from the Orillia Public Library about an item on Fred Rickwood, the response of Amy Lambertsen, who runs the library’s Local History Room, was immediate, helpful, and generous. What a wonderful librarian!

Lisa Lawlis, Archivist at the County of Lennox and Addington Museum and Archives, was thoroughly efficient, encouraging, and supportive through all the many hours of her time that I monopolized. What a wonderful archivist!

Jane Lovell, a member of the Adolphustown-Fredericksburgh Heritage Society, researches and writes about local history. She has a special interest in the Herrington family and Camp Le Nid and generously corrected errors in and contributed information to the second and third volumes of this book. Jane works tirelessly in promoting the preservation of local history and the dissemination of knowledge about it. I am very appreciative of her contributions to this project.

Margaret McLaren, a golf historian with a main focus on the Rivermead Golf Club, kindly informed me of Fred Rickwood’s work at the Belleville Golf Club and supplied newspaper clippings about it. I thank her for this important contribution.

I thank Sandy Gougeon, a granddaughter of Bill Brazier, for kindly correcting several inaccuracies in my account of Brazier’s life and for helpfully supplying further information about and photographs of her grandfather.

I also thank Karen Hewson, Executive Director of the Stanley Thompson Society, and Lorne Rubenstein, Canadian golf journalist and golf writer without peer, for encouraging words in support of my research on Fred Rickwood.

Dr. T.J. Childs was extraordinarily helpful in discovering information, documents, and photographs about a large number of the people whose stories are highlighted in this book. His genealogical skills are extraordinary.

Vera Childs donated funds to provide access to important rare photographs that were essential to my telling of the story of the earliest development of golf in Napanee. I thank her for her generous support of this project.

I am grateful to Janet Childs for her patience and forbearance during my work researching and writing this book, and I am especially grateful for her hard work in preparing this book for publication.

Perhaps most important to a book like this, however, is the pioneering work on the collection and interpretation of local archival information about the golf course by Art and Cathy Hunter, and their band of fellow researchers, published as Golf in Napanee: A History from 1897 (2010). To contribute to what they started is a pleasure and a privilege.

Preface

If you Google the name “Fred Rickwood,” your search will yield little beyond the fact that he participated in a number of Canadian Open and Canadian PGA golf championships in the first quarter of the twentieth century.

The search might also reveal an image of his grave marker in Toronto’s Prospect Cemetery.

Figure 1 Fred Rickwood grave marker, Prospect Cemetery, St Clair Avenue, Toronto.

The gravestone tells us little about Fred Rickwood. Apart from his name, date of death, and age, he is identified only as Company Quarter Master Sergeant Fred Rickwood of the 26th Battalion of the Canadian Expeditionary Force.

So much is missing.

There is not even a date of birth, and so perhaps it is not surprising that the age given is wrong.

Most importantly, there is nothing about his life in Canadian golf, which is a great shame, for golf was the main reason for his Canadian life.

This book is an attempt to honour Fred Rickwood by remembering his life in early Canadian golf, particularly with reference to his design of the Napanee golf course.

The greatest legacies that golf course architects leave golfers are their golf courses – the ones that endure as times change and continue to engage the interest of golfers as each new golfing generation emerges. In Nova Scotia and Ontario, several of Rickwood’s golf courses remain in play, hosting many thousands of rounds of golf each year. The oldest of his golf courses is 110 years old; the youngest, a spritely ninety.

Long may Fred Rickwood’s legacy golf courses last – especially that of the Napanee Golf and Country Club!

Introduction

In an article celebrating Napanee Golf and Country Club’s emergence into a third century since its opening in 1897, Flagstick magazine observes that “There is no designer of record for Napanee. Much like the historic courses of the United Kingdom, its nine holes (but ten greens and with eighteen separate tee locations) were crafted gradually – with renovations taken upon by the membership when it has been deemed necessary” (8 June 2007).

To say that there is no designer of record for the Napanee golf course is true enough, as far as it goes. Yet the absence of a designer of record is not a matter of a missing designer, but rather a matter of missing records. Or more accurately yet, it is a matter of not inspecting the existing records closely enough.

For closer inspection of the records reveals that there was indeed an identifiable designer of the Napanee Golf and Country Club’s course, that his work dates from what is known as “the Golden Age” of North American golf course design, and that his golf course design mentor was the greatest of all Canadian golf course architects: the legendary Stanley Thompson.

In Golf in Napanee: A History from 1897 (2010), Art and Cathy Hunter reproduce two 1927 articles from local newspapers that draw attention to a visit to the Napanee Golf and Country Club that summer by a pair of golf professionals, one of whom would exert a fundamental and continuing influence on the playing of golf in Napanee.

The Hunters draw attention to the following item in the Napanee Beaver (10 June 1927):

GOLF MATCH

The match played here Wednesday afternoon was a very interesting game and was followed by a large crowd of spectators. Bill Brazier, British Professional of Toronto, was paired with George Faulkner, a young amateur from Belleville Country Club, against Fred Rickwood, British Professional of Toronto, and W. Kerr, Professional at the Cataraqui Golf Club. On the first round Brazier and Faulkner were two up and held the same lead during the second round. Brazier made a score of 76, for the 18 holes, which is good, considering that the greens are not in a fit condition for putting. He plays a very steady game and seldom got in any difficulty. His partner, George Faulkner, got in trouble several times on the first round, but played a 39 in the second round and if he continues, he should soon be heard of in the Canadian Championship matches.

Rickwood had 40 for each round and had three penalties. He played a very sporting game and took chances rather than playing safe, which of course pleased the spectators. He made some great recoveries after getting in difficulties. Kerr could not seem to get going in the first round, and the course did not seem to be to his liking, taking a 47 the first round. However, he improved in the second round and made a 39. Final scores, Brazier 76, Faulkner 84, Rickwood 80, and Kerr 86. After the game Brazier gave a very excellent demonstration of how a ball should be driven with the different kinds of iron and wooden clubs and apparently could make the ball do anything he wished. Both Messrs. Brazier and Rickwood have been very busy giving lessons to the local members, and all are delighted with their work. Brazier's two lectures have been most instructive to golfers. Rickwood, besides being a good instructor, is an expert in laying out courses and building greens, and has during his stay, laid out a new green and practically completed it.

The Management of the Club were very fortunate in securing their services, and it is to be hoped they will return in the near future, as there are many who have not had the chance to obtain lessons from them.

The Hunters also note the following piece a few days later in The Napanee Express (14 June 1927):

GOLF WEEK

Last week the Napanee Golf and Country Club staged an interesting and profitable week for its members. Messrs. Bill Brazier and Fred Rickwood, two well-known professional golfers, spent the week at the course, giving lessons to those asking for them, and repairing and selling clubs and advising the members on any golf matters at request. On Monday Mr. Brazier, who is a wonderfully fine golfer and a splendid teacher, gave a lecture on wooden clubs, and on Wednesday evening an exceedingly interesting lecture on iron clubs. On Wednesday afternoon Messrs. Faulkner, of Belleville, and Kerr, of Kingston, played an exhibition game with Messrs. Brazier and Rickwood. Eighteen holes were played, … Brazier and Faulkner ... winning the match. The golfers who attended the game were treated to a fine exhibition…. Mr. Rickwood, who has had years of experience in laying out golf courses, has prepared a plan for the improvement of the Napanee course, and while here laid out and completed a new number one green. Messrs. Brazier and Rickwood will return here in August to lay out further improvements in the course. Both gentlemen were delighted with the Napanee course, stating that the fairways were the best in Ontario, and with improvement to the greens the course will be one of the very best nine-hole courses in Ontario. A large number of the Napanee enthusiasts received instruction from the professionals, keeping their time fully occupied during their stay.

Who was this Fred Rickwood? Who was this Bill Brazier? And how did they come to be barnstorming the province on a fix-your-swing, fix-your-clubs, fix-your-course mission?

In particular, what can we learn about this “course-whisperer” Fred Rickwood and how he had accumulated “years of experience in laying out golf courses”? What might it have been in his “years of experience” that led the management of the Napanee Golf and Country Club to commission him, rather than another golf course architect, to present plans for the improvement of its golf course?

We note that the one newspaper indicates on June 10th that it was “to be hoped they will return in the near future,” whereas just four days later we read in the other newspaper that “they will return here in August to lay out further improvements in the course.”

Their return was to be in the very near future, indeed! And their plans for that return went from vague to certain in just four days. Their June visit must have impressed the golf club. What was it that convinced club management to let course designer Fred Rickwood lay out a new and improved course that August?

These questions are important for lovers of the Napanee Golf and Country Club, for the present routing of the golf course is largely due to his work late in the summer and early in the fall of 1927. Five of his 1927 greens are still used at the Napanee golf course, and on holes where his original greens have been replaced, his fairways and tee boxes are still in use.

So here is our missing designer of record: Fred Rickwood.

A Word on the Organization of the Book as Four Volumes

This book, A Forgotten Life in Canadian Golf: Remembering Fred Rickwood and the Making of the Napanee Golf Course, is presented in four volumes.

Volume One, The Course of Fred Rickwood’s Life: From Ilkley to Orillia, presents the biography of this Canadian golf pioneer.

Volume Two, Napanee Golfers and their Courses to 1906, provides biographies of the earliest known golfers in Napanee, discusses the golfing grounds where golf was first played in the area, and discusses the first golf course laid out in 1897 and used down to 1906.

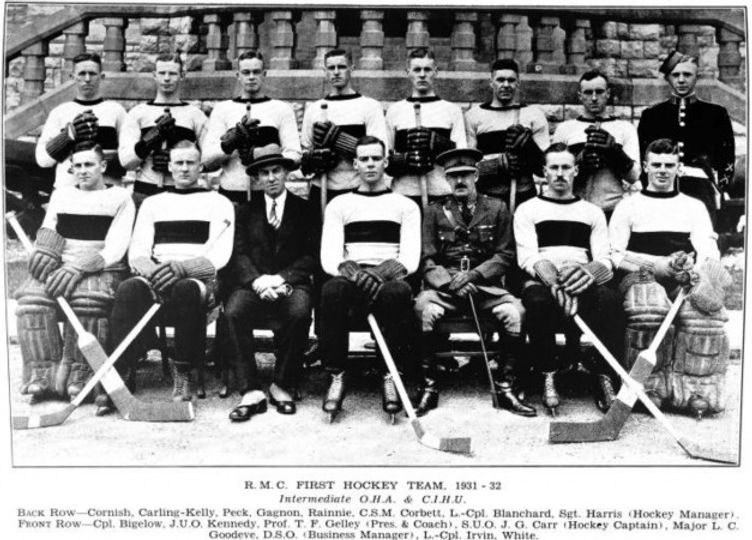

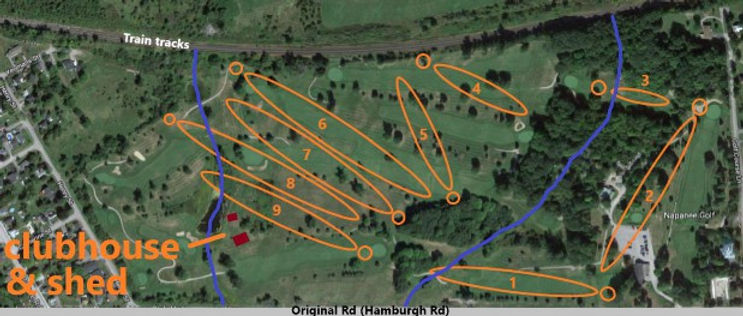

Volume Three, The 1907 New Course and Four of Its Players, discusses the first nine-hole golf course laid out for the Napanee Golf Club, presents photographs of the 1907 design, and presents biographies of the four golfers who appear in the photographs in question.

Volume Four, Blending Penal and Strategic Design at Napanee, reviews the architectural principles that Rickwood learned from mentors like Stanley Thompson and analyzes in Rickwood’s design practices at Napanee his implementation of principles associated with the 1910-37 period of golf course construction that Geoff Shackleford calls The Golden Age of Golf Design (Sleeping Bear Press 1999).

Volume Three: The 1907 New Course and Four of Its Players

Why a New Course in 1907?

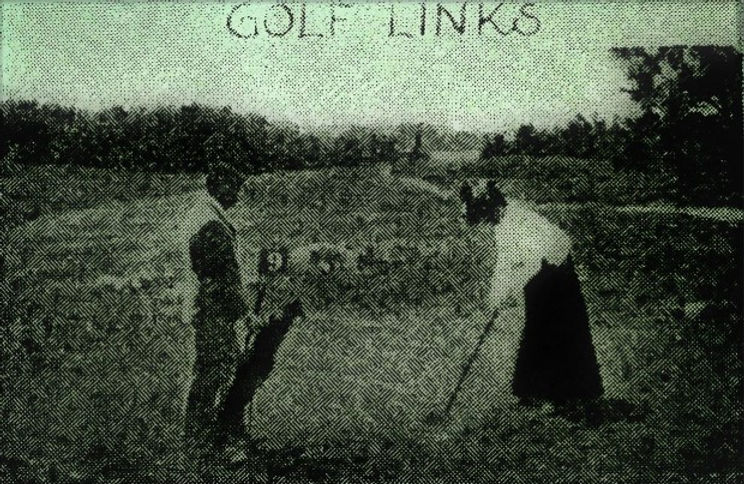

That there was a “new course” opened in 1907 is a fact. As the Hunters note: “On May 3, 1907, it was reported that, ‘The Napanee Golf Club’s new course was opened for play.’ The members concluded that it was much more difficult than the old course and although the greens were not in good condition yet, ‘when completed, will make a first-class course.’ ‘The panoramic view from Blanchard’s hill is of the whole course and adds materially to the pleasure of playing’” (Golf in Napanee: A History from 1897 [Napanee 2010], p. 8).

Just what factors motivated the still young Napanee Golf Club to build a new course during the 1906 golf season is not clear. Yet we can imagine a number of possible motivations.

I suggested in the previous volume of this book that if the layout of the 1897-1906 golf course comprised five holes laid out in parallel, then members of the Napanee Golf Club could quite easily have played their five-hole course as a nine-hole course. Once a group of golfers had finished the fifth hole, it could return to the clubhouse by playing its way back on the very holes played on the way out. That is, after completing the fifth hole, the group would play the fourth hole as its sixth hole, the third hole as its seventh hole, the second hole as its eighth hole, and the first hole as its ninth hole. Of course, whenever a group on the way out encountered a group on the way in, the two groups would have to alternate in teeing off on the tee box where they met. Such a thing would be cumbersome if the course were full. In the early years, however, membership was low and the number of club events was small (even at the weekly club tournaments mentioned in the newspapers of 1910 there were as few as five players), so crowding on the five-hole course was probably rare.

Still, the game was increasing in popularity at the beginning of the twentieth century, and the club was picking up new members as time passed. There is little doubt that members would have anticipated fairly early on that they were eventually going to need a bigger course to accommodate a growing membership.

Similarly, official tournament play required 18-hole scores, so the prospect of enabling an eighteen-hole score by two circuits of a nine-hole course rather than by directing tournament traffic across four circuits of a five-hole course would have been very attractive.

The construction of a nine-hole course, as opposed to an eighteen-hole course, would have been the Napanee Golf Club’s ambition, for even if it were to secure access to all of Lot 18 of Concession 7 in North Fredericksburgh Township, the available land was at most 98 acres, and the consensus was that about 50% more land than that was the minimum required for eighteen holes (if golfers were not to be put in danger of being struck by the golf balls of players on other holes). Besides, in the early 1900s, the nine-hole course was the normal size of small-market golf courses. A golf club in a small market aimed for eighteen holes only when the golf club membership became so large that its nine-hole course became too crowded to accommodate all the members who wanted to play.

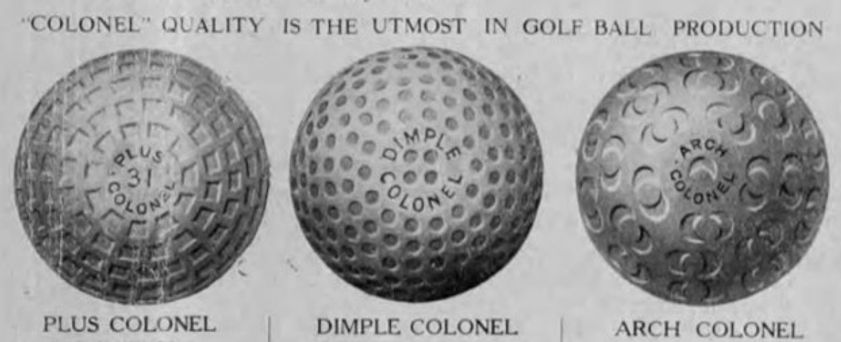

Another factor leading to the alteration of golf courses like Napanee’s in the early 1900s was the invention of a new golf ball.

When the Napanee Golf Club was founded in 1897, the golf ball then in use was the gutta-percha ball, or guttie (made from the rubbery sap of a Malaysian tree). In his 1898 book Golf, Gardener G. Smith explained to Americans new to the game that “The ball used in playing golf is made in various sizes, but that most in use measures about 1 ¾ inches in diameter. It is usually made of well-seasoned guttapercha, grooved or notched on the surface and painted white” (New York: Frederick A Stokes Co, 1908, pp. 11-12.). Companies selling golf balls would take orders for gutta-percha balls that would be available in six months’ time, after seasoning. Golfers could also buy cans of white and red paint for golf balls, since the gutta-percha rubber would not retain its paint well, and so balls would return to their natural black colour after several rounds of golf.

The gutta-percha golf ball was gradually replaced in the early twentieth century after the invention of the rubber-wound,rubber-core golf ball by a man named Haskell, who patented it in 1899. This ball – called the “Haskell Flyer” – flew 20 yards further than the gutta-percha ball. The latter had not been dimpled, but rather scratched and scored in various ways when golfers discovered that the gutta-percha ball that was roughed up after play (losing its perfectly smooth manufactured surface) flew further than when new and could be played with better control by the golfer. These discoveries led to the study in the early 1900s of the aerodynamic effects of dimples on a golf ball. When the new rubber-wound, rubber-cored golf ball received dimples, it flew another twenty yards further. After both the British and US Opens were won in 1902 by players using the new rubber-wound,rubber-cored ball, it became the golf ball of choice. The gutta-percha golf ball went the way of the Dodo bird.

By 1906, the increased distances that golfers could now hit golf balls must have been one of the factors leading the Napanee Golf Club to re-design its golf course in 1906. After all, the Ganton golf course in Yorkshire where Harry Vardon was the golf professional from1896 to 1902 had to be re-designed for this very reason shortly after Vardon left in 1903, as Bernard Darwin explains: “Some of the glamour of Harry Vardon still hangs around Ganton, although he has left it now for some years …. The course has been altered a good deal since Vardon’s days, for with the advent of the Haskell, it suffered the common lot and became rather too short” (The Golf courses of the British Isles [London: Duckworth, 1910], pp. 130- 31). The effect of the new golf ball was so dramatic, in fact, that many golfers in Britain and America called for it to be banned, for it was making too many existing golf courses play too short. Napanee Golf Club must have found this to be the case, for its original five holes had too many two-shotters just over 200 yards.

Figure 2 Experimentation with dimple patterns was rampant in the early twentieth century. See the patterns above offered by the "Colonel" golf ball company. Canadian Golfer, May 1920, vol vi no 1, p. 1.

The Napanee Golf course probably also wanted to be able to host other golf clubs on a golf course comparable to the golf course of its main competitors: comparable in terms of the quality of its tees, fairways, and greens, and comparable in terms of its length and in terms of the challenges it posed.

Recall that the earliest reference to golf in Napanee that the Hunters could find consisted of a newspaper report from November of 1905 which indicated that Napanee golfers had travelled to Kingston to compete with golfers there. I do not think it is a coincidence that in the 1906 photograph of Mary Vrooman at the club shed (a photograph that we studied so closely in the previous volume of this book) we see signs of construction activity on the golf course.

The Napanee golfers who travelled to Kingston for this competition included the men who would be President and Vice-President of the Napanee Golf Club in 1907, as well as members who would form the core of the men’s competitive team for many years to come. The President was Dr. Raymond Alonzo Leonard (physician and postmaster, and Napanee cricketer and curler from way back), and the Vice - President was John Wesley Robinson (owner of the big department store on Napanee’s main street, and also a champion Napanee curler). The golf course that they played on in Kingston was the home of the only golf club then located in Kingston: the Kingston Golf Club (the first nine holes was not built at Cataraqui until 1917, when Charles Murray came from Royal Montreal to lay out the course).

The Golf Annual of 1897 writes that the Kingston Golf Club’s “course is beautifully situated on government reserve ground near Fort Henry, overlooking the River St Lawrence, and the first of its famous ‘Thousand Islands’ group. It consists of thirteen holes, the first three and the last two of which are played over twice to complete the full eighteen. The hazards are marshes, roads, heights, and hollows” (Vol 10, p. 347). The Kingston Golf Club was important in the world of Canadian golf in those days: founded in 1886, it was a founding member of the Royal Canadian Golf Association in 1895.

Figure 3 Late 1800s photograph of a golf hole on Barriefield Common with a fence around the green to keep cattle off of it. The building at the top of the hill is the Barriefield School, at the north-east corner of Barriefield Common at the intersection of Main Street and James Street.

Five of the Kingston Golf Club’s holes were laid out over the Barriefield Common (see above).

The quality of the golf course that we see in the above photograph of a golf hole on the Barriefield Common in the 1890s does not seem significantly different in quality from the Napanee golf course of 1897-1906. The green is marked by a circular fence to keep the cattle off it. The “fair green” (as the fairway was called in those days) does not seem to have a clear distinction between fairway and rough. There are no bunkers, ditches, ponds, or trees – apparently no hazards at all.

Recall, however, that we noted in Volume Two of this book that the Kingston golf course wasredesigned in 1897 to make it accord better with the expectations of the American tourists who visited it. Eight years before the Napanee golfers’ 1905 visit, the Kingston Golf Club had undertaken a complete renovation in quest of such “first-class” status: “The Kingston golf club is making new teeing on the Barriefield links, and also intends entirely renovating the putting greens. Men are now at work making the improvements, which will make the grounds second to none in America” (Daily Whig, 17 April 1897).

I suspect that it was the experience of a proper golf course in Kingston in 1905 that almost immediately led to the making of plans in Napanee for its new course. The Kingston Golf Club must have had the kind of “first-class course” that Napanee aspired to have.

Note also that the Picton Golf Club was also scheduled to open a new nine-hole course in 1907. The first golf club in that town had been formed ten years before, a notice in Napanee Express observing that “A golf club has been organized in Picton” (8 October 1897). Napanee golfers would have been well aware of the improvements planned for this other local golf club.

With its new course of 1907, the Napanee Golf Club was no doubt trying to keep up with the Joneses in Picton and Kingston. Napanee golfers venturing into competition at other regional golf courses like the ones in Picton and Kingston would ultimately have to reciprocate the hospitality shown: they would have to invite these golf clubs to play competitions at Napanee. The prospect of not being able to host other golf clubs in the style to which such golf clubs were accustomed on their home courses would have been mortifying to the bankers, doctors, lawyers, and businessmen who made up the membership of the competitive men’s team at the Napanee Golf Club.

Golf was developing so quickly – there was the new golf ball, on the one hand, and there were younger and stronger golfers being attracted to the game, on the other hand – that a golf club that did not keep up with the times could be left behind. It seems that the Kingston Golf Club itself, which once set the standard locally, was in due course one of those left behind. The editor of Canadian Golfer explained the slow demise occurring at the Kingston Golf Club when he welcomed the development of the new Cataraqui Golf Club (laid out by Charles Murray in 1917): “They have played golf at Kingston since the eighties and it was probably for this reason that the course did not improve. What was good enough for a few players twenty-five years ago continued to be good enough for those who continued in the game. As a result membership remained very limited, and there was nothing to induce new membership to join” (vol iv no 8 [Dec 1918], p. 429).

By 1925, the Kingston Golf Club had been displaced by the Cataraqui Golf Club, and so it was disbanded and its golf course abandoned.

No such fate befell the Napanee Golf Club.

Finally, the laying out of a new nine-hole course in 1907 may have had something to dowith the Napanee Golf Club’s acquiring a long-termlease forthe land where the golf course was located. The Weekly British Whig reported before the beginning ofthe 1908 golf season that “The Napanee Golf Club has rented the Cartwright farm fora term of years and use the residence upon the farm as a club house” (2 April 1908, p. 3). It may be that this lease had been negotiated in 1907 and that the Napanee Golf Club concluded that financial investment in developing the Cartwright property would be worthwhile now given the long-term control of the land that had been acquired. The club certainly seems to have had big plans for its property: “Ithas decided to build a tennis court, and a bowling alley” (Weekly British Whig, 2 April 1908, p. 3).

There would be no tennis court or bowling alley, of course, but there would be money spent on the golf course.

Where was the New Course of 1907 laid out?

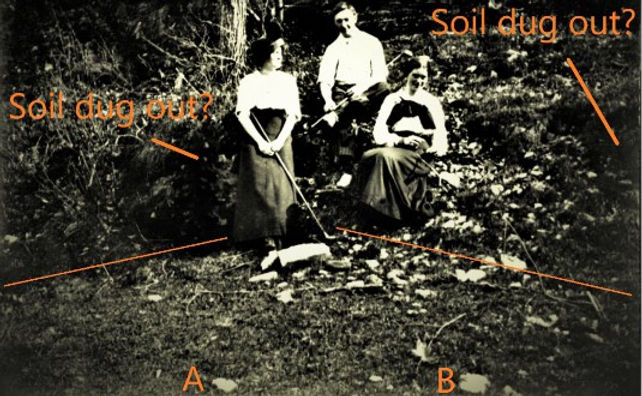

If the suggestions in Volume Two of this book about the nature of the 1897-1906 golf course are correct, then we can tell from contemporary documents – both the scorecard for the new course of 1907 and several photographs of golfers playing the course in 1912 (documents to be examined closely in the sections that follow) – that the new course was made not just by adding four holes to the original course, but also by lengthening four of the old holes. One hole remained the same.

Photographs and scorecard indicate that the first three holes of the 1907 course more or less corresponded, in the same order, to the last hole and the first two holes of today’s course.

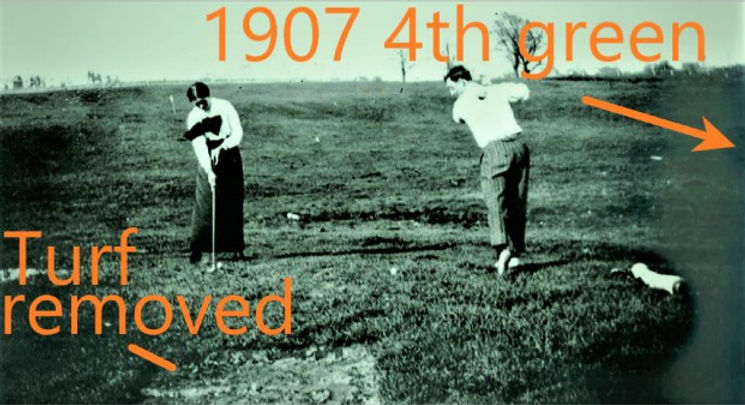

Photographs establish that the fourth hole of the 1907 course proceeded 209 yards diagonally across today’s third fairway to a green by the fence-line at the railway tracks at about the level of the 150-yard mark in today’s fairway.

The 215-yard fifth hole of the 1907 course seems to have been the same fifth hole of the 1897-1906 course that Herrington and Hall played in 1906 (we studied closely the photograph of Herrington and Hall about to tee off on this hole in Volume Two of this book).

We shall see that the last four holes of the 1907 golf course largely occupied the same area as the first four holes of the 1897-1906 course, but that the new holes seem to have been considerably longer than the old holes.

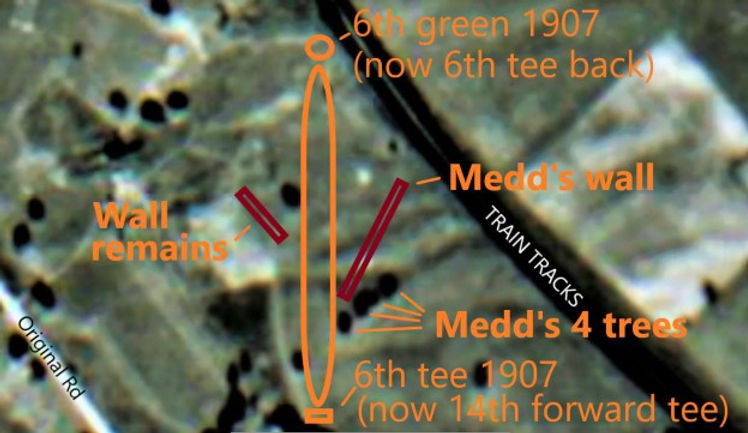

The sixth tee of the 1907 course was probably the fourth tee of the 1897-1906 course. But it cannot have run parallel to the fifth hole (which was identical on the two courses) back to the flag we see behind Herrington in the 1906 photograph of her and her partner Hall. The distance of that old fourth hole paralleling the fifth hole was about 215 yards, whereasthe length of the sixth hole of the 1907 course was 427 yards. This sixth hole concluded in a green at the fence along the railway tracks. A draughtsman’s compass describing an arc of 427 yards from the most forward tee on today’s fourteenth hole pretty much prescribes the radius within which the green would have had to have been built: the back tee on today’s sixth hole.

Thereafter, as we shall see, the final three holes of the 1907 course seem to have paralleled the new sixth hole, the ninth hole being a lengthened version of the original first hole on the 1897-1906 golf course.

A detailed discussion of each of these nine holes follows. Those who wish to see how the nine holes mentioned above are located relative to the present golf course may consult the Appendix at the end of this volume, where they are drawn onto a contemporary satellite map of the Napanee Golf and Country Club property.

The Napanee Golf Club was evidently pleased with its new course of 1907, for we read the next year in the Weekly British Whig that “The Napanee Golf Club has rented the Cartwright farm for a term of years and will use the residence on the farm as a club house” (2 April 1908, p. 3).

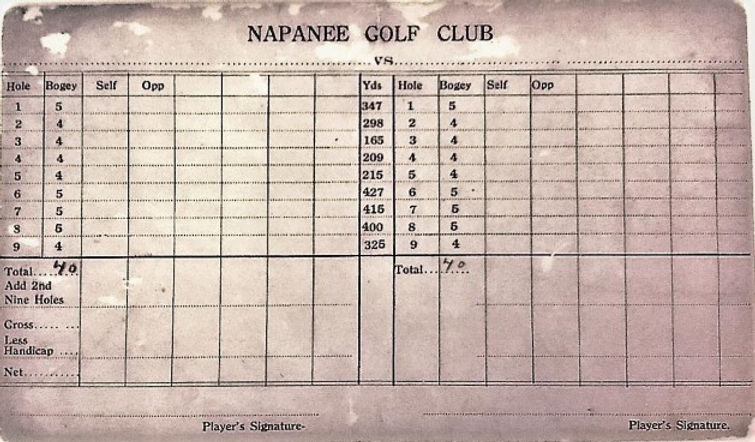

The Scorecard of the 1907 New Course

The scorecard of the 1907-27 golf course will strike modern eyes as unusual in a number of respects.

Figure 4 The scorecard for the 1907-27 golf course of the Napanee Golf Club. Item A-2013.026. Courtesy of the County of Lennox and Addington Museum and Archives.

The yardage of the individual holes is not given as a total.

The golf holes are not ranked in terms of level of difficulty.

Rather than there being a par indicated for each hole, we find a number referred to as “Bogey.”

The total of the “Bogey” scores for each hole is not printed on the card, but someone has written in the total by hand: 40.

The first two columns for recording scores indicate that the columns are for “Self” and “Opp[onent].”

The latter point is explained by the fact that in the first third of the twentieth century, the usual form of golf competition at Canadian golf clubs was match play. The preference for match play over medal play (or stroke play) was therefore a prominent feature of golf course architecture at the time: Stanley Thompson, for instance, believed that the last hole of a lay-out should always be a difficult hole so that a golfer leading a match by one hole should not be able to stroll to an easy victory by means of an easy final hole.

That golf holes were not ranked according to their level of difficulty is probably a sign that this scorecard dates from a time closer to 1907 than 1927, for handicap systems were not standardized in Britain or North America in the early years of the twentieth century. When the Napanee Golf Club was founded in 1897, debate raged as to how a match ought to be handicapped: should weaker players be granted a stroke or two for every hole, or should they be conceded a certain number of holes at the start of the match and be forced to play the better player even on all holes?

The most widespread way of determining a stroke handicap for players before World War I was simply to average a golfer’s three best scores of the year and then subtract from the number produced what was in the nineteenth century called the “ground score” – which was defined as the score that a firstclass golfer would make on a golf course were no mistakes made. The difference between the two totals would be the player’s handicap.

The scores and handicaps reported in the newspapers of 1910 and 1911 show the best golfers at the Napanee Golf Club scoring from the high forties to the mid-sixties, earning handicaps of from thirteen to twenty-five. Clarence M. Warner maintained a handicap of fifteen over the two years in question, suggesting that his three best scores were an average of fifty-five (producing a handicap of fifteen when the ground score of forty was subtracted). In a summer weekly competition in 1910, Warner’s score (gross, handicap, net) was given as “58 – 15 = 43” (Napanee Express, 8 July 1910). In a weekly competition one year later, his score was “52 – 15 = 37” (Napanee Beaver, 30 June 1911).

Of course good golfers regularly played to their handicap, since their scores were generally very consistent, whereas average golfers and bad golfers played to their handicap less often because their scores varied much more widely. In other words, the three best scores accumulated over a season were less a departure from their overall average score for good players than for other players.

The case of John S. Ham is a good example. In 1911, he began the year with a handicap of twenty-five but ended the year with a handicap of twenty-two. In May, the average of his three best scores was sixty-five; in September, the average of this three best scores was sixty-two. But such a golfer’s best and worst scores are widely divergent. In a weekly tournament in June, he scored terribly: “76 – 22 = 54” (Napanee Beaver, 30 June 1911). In May, however, in “The First Weekly Tournament … held on the local links on Wednesday afternoon …. Mr. John S. Ham easily won the best net with the lowest net score ever made in a tournament in Napanee …(54-25=29)” (Napanee Express, 19 May 1911).

Sandbagger!

Note also that many golf clubs did not establish a theoretical scratch score for their golf course. As Walter J. Travis observes, “In establishing handicaps it is customary to work up from the best player in the club, who is rated at scratch” (Practical Golf [New York: Harper and Brothers, 1902], p. 173). Designating a club’s best golfer as the “scratch” player in relation to whom all other members were handicapped – even if their best golfer was not very good – clearly meant that handicaps at one club were likely to be out of line with the handicaps of members at other clubs.

Another problem was that it was up to each individual golf club to determine what a proper score was for each hole, and therefore what a proper score for the course as a whole was. The vanity of influential club members might result in the club deciding that the proper number of strokes to complete a certain hole was five, instead of four. A similar hole on another course might be regarded there as properly played in four strokes, rather than five. So two golfers of indistinguishable ability would have very different handicaps depending on where they played golf.

Still to be determined was a more accurate mathematical system for working out a player’s handicap than the best-three-scores method, a system for establishing the proper score for a golf hole and a golf course regardless of the preferences of club members, a system for comparing the difficulty of one hole to that of another, and a system for comparing the difficulty of one golf course to that of another.

Accurately determining the yardage of golf holes and golf courses and deciding upon a consistent standard for determining the “ground score” of each golf course would be essential in moving forward with a viable handicap system.

Measuring Yardage

If we add up the yardages of the nine golf holes on the scorecard reproduced above, we find that the total is 2,801.

In the American Annual Golf Guide from 1920 to 1923, the yardage for the course is listed as 2,801. In the issues from 1925 to 1927, the yardage is listed as 2,893. (From 1928 onward, after Fred Rickwood’s re-design of the golf course at the end of 1927, the yardage is listed as 2,750.) So we know that the scorecard we are studying dates from before 1925. And it seems likely that the yardage provided to the American Annual Golf Guide in 1920 reflected the yardage of the golf course in 1914, for the Hunters indicate that the golf club became relatively moribund during World War I – suggesting that there would have been no construction projects carried out on the course during the five years in question from 1914 to 1919.

In 1920, the Napanee Golf Club seems to have decided for the first time to broadcast far and wide the fact that it existed. The first mention of Napanee in the American Annual Golf Guide occurs in 1920, and in the spring of 1920 Secretary-Treasurer Tom German wrote to the editor of Canadian Golfer with news about the election of the club’s officers that year, and he also mentioned, by the way, that the professional course record holder at Napanee Golf Club was Karl Keffer, the Canadian Open Champion of 1909 and 1914, and co-second-place finisher in 1919 – tying with a young sensation named Bobby Jones from Atlanta.

Not all of the numbers that German provided were absolutely correct, mind you. He indicated that the golf club was founded in “1900.” And for some reason, whereas German told the American publication that the course was 2,801 yards, he told the Canadian publication that the yardage was 2,800.

Perhaps something to do with the exchange rate then ….

Note that more than a century ago, golf course yardages were determined not via measurement through the air (as they are now, via GPS and lasers), but rather via measurement along the ground – that is, by measuring contours via a yardage wheel run along the ground (also called a surveyor’s wheel, perambulator, or waywiser), following an imaginary line down the centre of the fairway, all the way from the centre of the tee to the centre of the green.

Figure 5 This antique folding metal surveyor's wheel would have been the kind of device used for measuring the yardages of the golf holes at Napanee Golf Club a century.

Consider the difference that the two methods of measuring distance on the “Gully Hole” would produce. Through the air, the distance from the front of the middle valley tee today to the centre of the green is about 160 yards. But running a yardage wheel down one side of the gully and up the other side would indicate a distance of perhaps 200 yards, or more.

This general point is made by Alan D. Wilson in a 1920s essay on “The Measurement of Golf Holes”:

The question is constantly asked whether holes should be measured in an air-line or along the contour of the ground. For practical reasons the contour of the ground is usually the better method. In the first place it is much easier …. If the play is over rising ground followed by falling ground and then another rise, it is true that the contour method slightly increases the length …. Of course, in certain exceptional cases, the air-line method should be used. Let us take, for instance, a one-shot hole of, say, 160 yards in a direct line, played from a high tee over a deep ravine to a high green beyond. The air-line measurement would be 160 yards. If a contour measurement were used, following down into the ravine and up the other side, it might show a distance of 200 yards, which would be entirely misleading, as the contour of the ravine in no way enters into the shot. In general, then, for the sake of practical convenience, holes should be measured on the contour of the ground; but in the unusual case where the contour does not enter into or affect the play of the shot, the air-line method should be used.(Bulletin of the United States Golf Association, Vol IV No 3, 24 March 1924, p. 74).

So when considering the yardages given for the 1907-1927 golf course in the various golf publications of the 1920s, bear in mind the measuring method. Does the difference between the yardage of 2,801 in 1923 and the yardage in 1925 of 2,893 mean that the course had been lengthened by ninety-two yards between 1923 and 1925, or merely that the course had been officially re-measured for the first time in twenty years and that the person walking along the ground from hole to hole had run the yardage wheel along a slightly different line from the one followed twenty years before?

Bogey versus Par

The references above to the “bogey” score for each golf hole may be unfamiliar to some.

For the first 500 or so years of golf history, there was no such thing as a par score for a golf hole or for a golf course. The goal of the golfer with regard to any particular hole was not to complete it in a particular number of strokes regarded as the theoretically ideal or normal number. One simply aimed to take as few strokes as possible.

So it was until the 1890s.

Then, as Robert Browning points out in A History of Golf: The Royal and Ancient Game (1955; reprinted Pampamoa Press, 2018), the concept of “ground score” was invented. At the golf club in Coventry, England, in 1890, the Club Secretary worked out a score for each hole, and thereby for a complete round of golf on the course, that first-rate golfers would achieve if they made no mistakes: he called it the “ground score.” His purpose was to create an ideal score that club members could try to match in their individual rounds of golf: a form of match play for a single golfer.

Within a year, the idea of establishing a “ground score” was adopted by the Club Secretary at the golf club in Great Yarmouth, England. There, one of the Club Secretary’s regular playing partners reacted in jocular frustration to his inability to match the “ground score” of the club’s “imaginary” ideal player: “This player of yours is a regular Bogey man!” He was alluding to a song popular in the early 1890s, “Hush! Hush! Hush! Here comes the Bogeyman!” whose lyrics about a mischievous, timorous, hard-to- catch goblin or bogey ran as follows:

Children, have you ever met the Bogeyman before? No, of course you haven't for

You're much too good, I'm sure;

Don't you be afraid of him if he should visit you, He's a great big coward, so I'll tell you what to do:

Hush, hush, hush, here comes the Bogeyman, Don't let him come too close to you,

He'll catch you if he can.

Just pretend that you're a crocodile

And you will find that Bogeyman will run away a mile.

The popularity of the club member’s witticism meant that the “ground score” at Great Yarmouth immediately became known as the “Bogey” score, and the practise of establishing a ground score and naming it the Bogey score spread like wildfire as Great Yarmouth club members played other golf courses throughout southern England. Soon, golfers all across Britain referred to the ideal player whose score they were trying to match as “Mr. Bogey.”

The Club Secretary at the military’s United Services Club in Gosport added one more element to this practice in 1892. Since all members of this club were required to have a military rank, their opponent could not be a civilian: so golfers at this club replaced “Mr. Bogey” with “Colonel Bogey.” The latter was made famous in the “Colonel Bogey March,” the British army bandmaster who wrote it having been inspired by a golfer who, rather than warning other golfers of a wayward ball with a shout of “fore,” instead loudly whistled two notes: the two notes of the descending musical phrase that begins each line of the “Colonel Bogey March” melody.

By the early 1900s, problems began to emerge regarding Bogey scores. What criteria should be used to determine Bogey?

In the United States, the Ladies Golf Association began searching in 1893 for a way of applying a standard in the determination of how many strokes it should take to complete a golf hole. This was to be a standard applicable no matter where the golf hole was found – regardless of the golf course, regardless of the country, regardless of the golf club’s traditions or wishes. The idea was to determine a proper score for every hole by means of its measured length. The United States Golf Association took up the idea and decided upon its standard in 1911: all holes up to 225 yards in length should take three strokes, all holes between 226 yards and 425 yards should take four strokes, all holes between 426 yards and 600 yards should take five strokes, and any hole longer than 601 yards should take 6 strokes.

In its determination of the number of strokes it should take to play its eighth hole, the Almonte Golf Club happened to agree with the standard that would be set several years later by the USGA. Otherwise, its values were very different. Remarkably, the club established five as the proper score for its third, fourth, sixth, and ninth holes, for each of which the USGA would later determine that the proper score was three. On the remaining four holes, the Almonte club allowed four strokes where the USGA would allow just three.

One can see that the USGA standardswere not applied to the Bogey scores of the Napanee Golf Club scorecard above: three holes of less than 226 yards are given a Bogey of four (rather than the three stipulated for such holes in 1911), and holes of 347, 400, and 415 yards are each given a Bogey of five (instead of the four stipulated in 1911). On only three holes at the Napanee Golf Club are the Bogey scores in accord with the USGA standards stipulated in 1911.

For its universal standards scores, American golf associations borrowed a term that traders in the stock market used to name the proper or normal value for a stock between the extremes of its high and low prices over time: “par.”

This term had been used in a similar context once before in golf, at the 1870 Open Championship at Prestwick.

Figure 6 "Young" Tom Morris, 1851-75, wearing the Open "championship belt" that he was given to own after winning it four times in a row. The belt was replaced by today's Claret Jug.

A golf writer reporting on the tournament had asked two golf professionals familiar with the twelve-hole golf course what the winning score for the tournament might be. The golfers suggested that a perfect score for a golfer who made no mistakes would be forty-nine. The writer for the first time invoked the stock-exchange metaphor to inform readers that forty-nine strokes would be “par” for the course. In the event, with a score two under the “perfect score” that the writer called “par,” twenty-year-old “Young” Tom Morris won the third of the four Open Championships he won in a row.

Latent here in 1870 was the concept of a “ground score” and the possibility of using the word “par” to indicate it, but nothing came of it.

Despite the American declaration in favour of standard par scores, golf clubs in Britain and Ireland maintained their use of the term Bogey, and individual golf clubs maintained their traditions of establishing their own Bogey scores according to the whims of the membership.

Where club members found a 400-yard hole very difficult to play, for instance, they were free (perhaps in service of nothing more than the vanity of influential club members) to declare its Bogey score to be five, rather than four (as according to the American standard).

Well, in the early 1900s, the scores of the best golfers in the game – both professionals and amateurs – were coming down dramatically. Golf swings were improving as tournament play increased at amateur and professional levels, allowing golfers to learn from each other better swing techniques in general and better swings for particular shots, to say nothing of better strategies for playing golf with the swings and shots that golfers now had in their arsenal. Furthermore, as we have already noted, new golf balls were being hit further and more accurately by the best players.

In the United States, where the practices of golf clubs in converting from their old Bogey scores to the new standard par scores was in flux, the best golfers regularly began to complete many of the golf holes graded with the old Bogey score in one stroke less than that score. So the terms “par” and “Bogey” began to diverge in American golf, as the best American golfers began to use the word “par” in reference to the perfect number of strokes for a hole and the word “Bogey” for one stroke more than the perfect number.

The American amateur champion Walter J. Travis explained his understanding of the two terms in 1902:

Par golf, it may be remarked, is perfect golf, determined according to the distance of the holes and with two strokes allowed on each green, while bogey simply represents the score of a good player who occasionally makes a mistake, not very glaring, but sufficient to make a difference in the round of four or five strokes. Bogey is an elastic quantity, however, so much so, indeed, on some courses, as to furnish no true criterion of the game of the player who now and then beats the Colonel! (Practical Golf, p. 173)

British golfers were understandably upset to learn how the word Bogey was coming to be used as a score meaning one stroke more than it took an American player to complete a hole! By 1914, just before World War I broke out, many British golf writers began to agitate for adoption of the USGA standards for determining the proper number of strokes for golf holes, but the war deferred further work on this idea. So it was not until 1925 that British and Irish golf Unions (as their golf associations are called) agreed to establish Standard Scratch Scores for all golf holes and golf courses.

Depending on how closely the Napanee Golf Club hewed to the advice of the USGA, the fact that the scorecard reproduced above shows Bogey scores rather than par scores, and the fact that so many of the Bogey scores diverge from the USGA standards of 1911, could be a sign that the scorecard dates from even before 1911.

Who designed the new layout?

Who found the four new holes at the south end of the course that would be added to the original five-hole layout to make up the new course of 1907?

Who decided that the fifth hole of the original course would remain unchanged in the new course?

Who figured out how to lengthen four of the original holes and for the first time to run a hole across the creek and deep, steep gully at the north end of the course?

Could it have been a committee of club members?

Or one club member in particular?

Or did the Napanee Golf Club hire a professional golfer to do the job?

Clarence M. Warner and Willie Campbell

Perhaps the collective golf wisdom of the most experienced golfers among the membership was judged sufficient to the requirements of designing a new course. Herrington had laid out a course at Camp Le Nid in the mid-1890s. Many club members were very familiar with the Kingston Golf Club, which had been upgraded to contemporary standards in 1897. But did anyone have first-hand experience of the kind of design that a professional golfer would lay out and the kind of work required to build it?

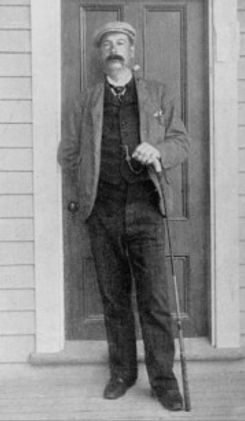

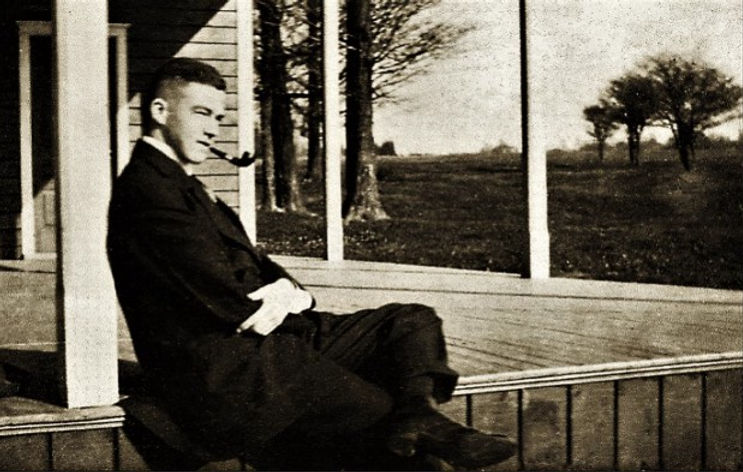

Clarence M. Warner may have had particularly relevant experience. In Rhode Island, he was not just an early member of the Wannamoisett Country Club (laid out as a nine-hole course by Willie Campbell in 1898, and redesigned as an eighteen-hole course by Donald Ross in 1914); he was also a founding “incorporator” of the club (Official Golf Guide of 1899, ed. Josiah Newman [New York, 1899], p. 291).

Figure 7 Willie Campbell plays from gorse and heather on a British links course in the late 1880s, when he finished second and third in the Open Championship.

Warner was one of eight men who got together in 1898 to establish this golf club and to commission Campbell to lay out a nine-hole design. He was barely twenty-four years old, and the golf club had 160 other members, yet Warner was named to the Finance Committee, as well as the Board of Governors, and he was also named one of the club’s four Officers as its Treasurer.

There is little doubt that he would have been one of the club officers who dealt with Campbell during the construction of the course. Campbell was subsequently appointed the professional golfer at the club for the summer of 1899. The question is whether Warner took a hands-on approach to the creation of the Wannamoisett golf course. . If he did, he may have accompanied Campbell as the latter laid out the course – as many club officers did when a professional golfer came to the club to route the golf holes through the club’s property.

Whether or not he discussed with Campbell the principles of golf course design that the latter was applying as he walked the land, Warner may well have learned by observation just what went into routing a golf course. It is possible that he had visions of golf course design dancing in his head when he returned to Napanee from Rhode Island in 1904: perhaps he agitated for the addition of golf holes to the south end of the property from the moment he played his first round of golf at his new club.

Figure 8 Willie Campbell circa 1890.

Willie Campbell, born in Musselburgh, Scotland, in 1862, was a former caddie to Bob Ferguson (regarded as the greatest golfer in the world in the 1880s), who coached him, and he had also apprenticed with Old Tom Morris. He was an excellent golfer. He was leading the Open Championship at Prestwick in 1887 by three shots with three holes to go when his ball came up against the sodwall face of a deep bunker. He refused to play out backwards, insisting on playing forward to get out. In a Tin Cup moment, he took half-a-dozen strokes to get out of the bunker, scoring nine on the hole, and losing the championship by three strokes.

After the round was over and the Claret Jug was awarded to the champion golfer of the year, Willie Campbell and his caddie were observed sitting on over-turned buckets on a side-street, sobbing.

The story goes that this was when he decided to emigrate to the United States and start a new golf life.

Whether or not that story is true, he went to the United States in 1894, becoming the head professional of the Country Club at Brookline, Massachusetts, laying out new holes for that iconic golf course, as well as laying out the first nine holes for several other Boston courses that would become foundational to the growth of the sport in Boston. He also went on to lay out courses elsewhere in Massachusetts, as well as in New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, and Rhode Island.

Campbell was clearly on his way to a place of importance in the early development of American golf. But his life was cut short by cancer. He died in 1901, having wasted away, when just thirty-eight years of age. Golf historians are left to wonder what he might have done if he had lived long enough to fulfill his potential as a golf course architect.

Figure 9 Willie Campbell in late 1890s around the time of his work at Wannamoisett.

Mind you, Campbell had not given up golf when he came to the United States. In the 1895 US Open, he was tied for the lead with six holes to go, when his shot came to rest against a wall; someone told him he would have to play back, to which he replied: “I never played back in my life!” In Tin Cup: the Sequel, obstinacy in a national championship once more produced a score of nine, and again he lost by three strokes (Brian DeLacey and John Pearson “Willie Campbell: a neglected champion,” in Through the Green [8], p. 12).

Despite his short life in America, Campbell has not been forgotten. Robert Muir Graves and Geoffrey S. Cornish observe that Campbell “became a pioneer in planning municipal golf courses in America – facilities that became significant in accommodating a tidal wave of people who were taking up the game…. Moreover, his wife Georgina became America’s first woman professional golfer” (Classic Golf Hole Design [Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley & Sons, 2002], p. 181). Georgina not only married him; she became his apprentice.

Figure 10 Georgina and Willie Campbell outside their pro shop circa mid-1890s.

Georgina Campbell, born 1864 in Musselburgh, had learned golf in Scotland and met her husband when she was a member of the gallery following him in one of his matches there. She became his assistant golf professional in Massachusetts, making and painting gutta percha golf balls and giving lessons to wealthy Boston women eager to take up the game. She had played the game long enough to have experienced the transition from the time in her youth when a woman who took a full golf swing was thought unladylike to the beginning of a new age when women’s golf was unthinkable without the full swing that she taught in Boston.

Figure 11 Georgina Campbell circa 1910s.

In 1901, Georgina Campbell beat out all male applicants in the competition to succeed her husband at Boston’s Franklin Park Golf Links (which Willie Campbell had convinced municipal authorities to build in order to make golf available to working-class golfers at a cost of just 12.5 cents for a daily ticket). The success of this adventure in municipal golf had made the position of head pro at this course a lucrative one. So the job competition was fierce.

Of course Georgina Campbell immediately became famous as golf’s first woman head pro. In an interview with Golfing magazine shortly after her appointment, she argued that golf was the perfect game for women: “It is not necessary to make any great effort when using the golf clubs. Hence it is grand exercise, with the exact amount of effort used which suits the golfer’s physique. The fine long walks over the slopes and ridges which is the golf course; the bright, soothing, green grass; the incentive to beat one’s opponent without going into violence – I could play the game forever” (19 September 1901). And it seems she nearly did: she held the head pro position at Boston’s Franklin Park Golf Links until her retirement in 1927, but she kept up her golf game almost until she died in 1953, in her ninetieth year.

Even if Warner had followed closely the design theory and practice of Willie Campbell, would he have learned thereby how to lay out a golf course? Or would he have learned a different lesson?

He might have concluded from watching Campbell work out the route of the nine holes at Wannamoisett that laying out a golf course was not a job for amateurs. Perhaps he convinced his fellow club members in Napanee to do what he and his fellow club members in Rhode Island had done: hire a professional.

Can We Identify a Pro Who Might Have Designed the New Course?

Recall that at just after Napanee’s new course of 1907 was laid out, Fred Rickwood went to Amherst, Nova Scotia, to lay out the first golf course there.

In 1908, three of the women leaders of the wealthier members of Amherst society – Mrs. McDougal, Mrs. Hickman, and Mrs. Hodgeson – decided that it would be a good thing for Amherst to have a golf club. Golf was said to provide good physical and mental exercise for the professional classes. So these three women canvassed their wealthy friends for the funds needed to start a golf club and build a golf course. Their industry matched their ambition, and so within a few weeks Amherst had its first golf club.

Next came the matter of a golf course: where to build it, and who to build it?

The golf club leased a farm in West Amherst from a man named Baker as the location for the golf course, and then it hired Fred Rickwood to take charge of building the course: he directed the team that “measured the fields, pegged off the tees and greens, and made play possible” (C. Pipes, “The Early History of Amherst Golf Club” [1939], p. 3, cited in Michael J. Hudson, “An Examination into the Development of Golf Courses in Nova Scotia [MA Thesis, Dalhousie 1998]).

There were less than two dozen professional golfers in all of Canada in 1908 and somehow these good ladies got hold of one. They had not found Fred Rickwood by luck. It was not the case that an unemployed golf professional was hanging out in their community. The golf enthusiasts in Amherst had probably gone for advice in the matter of hiring a professional golfer to Canada’s unofficial head pro: the professional golfer at the Toronto Golf Club, George Cumming.

And George Cumming probably arranged for Fred Rickwood to go to Amherst.

If the Napanee Golf Club had decided to use a professional golfer to lay out a new course in 1906, they would probably have written to George Cumming, too.

By 1906, Cumming was well on the way to becoming the “doyen” of Canadian golf professionals, and “Daddy of them all.” My best guess is that if indeed a professional golfer laid out a new course for Napanee Golf Club in 1906, it was probably George Cumming who did so, or one of his apprentices at the Toronto Golf Club who served as his assistant professionals.

In the early 1900s in Canada, there were few Canadian-based professional golfers able to lay out golf courses. There were only about two dozen professional golfers in all of Canada when the Canadian Professional Golfers Association was formed in 1911. As we know, Fred Rickwood was one of them – and one of the few based in the Maritimes. Albert Murray, one of Cumming’s apprentices, had designed a new route for golf at Cove Fields on the Plains of Abraham in 1905 for the Quebec Golf Club, when he was just eighteen years old. His brother Charles Murray, an even earlier apprentice of Cumming’s, had laid out a golf course in Caledonia Springs at the beginning of 1904. Hired by the Royal Montreal Golf Club shortly after this, he continued to build golf courses in Quebec and Ontario. He would build the first nine holes at Cataraqui Golf and Country Club around 1917. We recall that Percy Barrett was also active in course design in the Toronto area in those days (laying out Lambton in 1903 and Mississauga in 1906)

Figure 12 George Cumming, 1879-1950, head pro at the Toronto Golf Club from 1900 to 1950.

But George Cumming was the most active golf course designer and he was the most well-known in those days. Observing that Cumming “was one of the earliest Canadian golf course architects,” Ian Andrew suggests that “he was likely selected initially to design courses because of his Scottish heritage and his place of prominence at Toronto Golf Club, but Cumming turned out to be an excellent architect in his own right” (“The Architectural Evolution of Stanley Thompson”).

Any of the ardent votaries of the ancient game in Napanee who read the Kingston newspapers would have known that George Cumming was the biggest name in Canadian golf at that time. Even his hiring in 1900 was news in Kingston: “The Toronto Golf Club has secured the services of George Cumming, Dumfries, Scotland, as professional coach.

He is now on his way to Canada” (Daily Whig 17 March 1900). Cumming was just coming off his apprenticeship to Glasgow’s Andrew Forgan, a renowned Scottish golf professional and golf course architect (he was the son of St Andrews’ Robert Forgan whose exported hand-forged club heads were the staple of every North American club-making shop). Andrew Forgan had taken Cumming along on the latter’s first adventure in golf course design in 1893: Cumming had just turned thirteen. The Kingston newspaper announced twenty-year-old Cumming’s hiring by the Toronto Golf Club because the latter was one of the oldest, and at the time certainly the most important and most prestigious, of the golf clubs in Ontario.

Is there anything to suggest that Cumming was in some way associated with the Napanee Golf Club at this time? I think there is a piece of circumstantial evidence.

When George Patten Reiffenstein made his score of 39 in 1914, the newspaper reported that he had tied the professional course record. Who was this professional who had played the new course of 1907 sometime prior to Reiffenstein’s 1914 round?

I suspect that there was an exhibition match staged at the Napanee Golf Club in 1907 involving the course architect, returning to open the new course that he had designed. In those days, new courses were often officially opened by an exhibition match involving professional golfers associated with the professional golfer who had designed the course. This match would not occur at the golf club’s spring opening in May but rather in mid-summer when the weather was better and a good group of spectators might be expected to show up and accompany the professional golfers around the course.

Figure 13 Karl Keffer circa 1910.

The circumstantial evidence that Cumming was somehow connected with the Napanee Golf Club consists of the fact that what seems to have been the first professional scoring record for the Napanee Golf Club was held by Cumming’s apprentice from 1906-1909: Karl Keffer.

As noted above, an item in the May issue of Canadian Golfer in 1920 refers to the Napanee Golf Club and its course record: “The Napanee Golf Club, Ontario, which has an interesting course of 2,800 yards, recently had its annual meeting, which was of a thoroughly satisfactory character…. Karl Keffer, open champion of Canada, has the record of the Napanee course, a 37, made some years ago” (May 1920, vol v no 1, p. 52).

As we know from Volume One of this book, Keffer was in the Canadian army from the end of 1916 to the beginning of 1919, so the course record “made some years ago” was certainly accomplished no later than 1916.

Furthermore, there are no newspaper items about the Napanee Golf Club during the war years from 1914 to 1919, so it seems unlikely that a professional visited the golf course during this relatively moribund period. Remember also that we know that Keffer was a two-time winner of the Canadian Open – first winning in 1909, and then winning again in 1914. Because the Open Championship was not held during the war, Keffer was therefore also the defending champion at the next Canadian Open, played in 1919, when he tied for second place with Bobby Jones, with whom he played the first two rounds.

Figure 14 Keffer follow-through circa 1920.

It is inconceivable that a Canadian Open champion could have even played the Napanee Golf Course in those days, let alone set a course record while doing so, without someone at the golf club reporting such a momentous event in golf club history to one or more of the Napanee newspapers. As the Hunters point out, the only time news about the Napanee Golf Club appeared in the Napanee newspapers was when someone from the club reported it to the newspaper. Yet amid all the many reports provided by club members about minor events in those days, such as the weekly club competitionsinvolving as few as half a dozen members, there is nary a word about a professional playing the golf course, let alone a Canadian Open champion, who also, by the way, shot the lowest round ever recorded on the course.

It seems to me that Keffer cannot have played the golf course and set a scoring record any time after he had won the Open Championship. He must have played the Napanee golf course and set the scoring record beforehis first Canadian Open championship victory in the summer of 1909 – when he was still George Cumming’s assistant professional at the Toronto Golf Club.

We need, therefore,to consider a possible – and I think fairly plausible – scenario.

After their contest at Kingston Golf Club in November of 1905, Napanee Golf Club directors wrote to George Cumming for advice on the designing of a new golf course. Either Cumming, or Cumming and his new assistant professional Karl Keffer, or Keffer alone, or even Keffer and his fellow Cumming apprentice Fred Rickwood himself, came to Napanee in 1906 and laid out a new course. After the construction of the golf course, at least Keffer, and perhaps Cumming or Rickwood also, returned in the summer of 1907 to play a ceremonial round of golf to officially open the new course.

Whoever played alongside him, Keffer was the one who shot the score that was ultimately remembered: 37.

Why was there no mention of Karl Keffer in a Napanee newspaper?

Recall the discussion in Volume One of this book of the fact that the golf professional was seen as a mere tradesman by the doctors, lawyers, bankers, and businessmen who comprised golf club memberships in the early 1900s. Golf was the domain of the honourable gentleman amateur. When the first Open was played at Prestwick in the 1860s, for instance, referees accompanied every professional player to keep the record of his score out of a concern that he might cheat or misreport his score, whereas every amateur was trusted to play fairly and keep his own score. Such was the distinction between the attitude toward a gentleman and the attitude toward a working-class person who played golf for money.

Around the turn of the century, golf professionals were not as a group even as good as the best amateurs. Most course records were still held by amateurs in the early 1900s. It was not until the 1920s that Canadian Golfer began to note that course records had become the domain of professional golfers. Furthermore, golf professionals in Canada played in just one tournament per year until 1911: the Canadian Open Championship. Thereafter they played in two tournaments, for the Canadian Professional Golfers Championship was created in that year. The tournament play that would make celebrities of professional golfer celebrities was still decades away.

So if George Cumming himself would have been seen as socially below the club members who consulted him in 1906, what of his mere apprentice?

Assistant professional Keffer’s 37 must have seemed a relatively un-newsworthy event to golf club members at the time. It is certainly a fact that whenever Keffer shot his record score of 37, there was no mention of it in the newspapers. In fact, when Reiffenstein shoots the amateur scoring record in 1914, there is no mention of the name of the professional golfer whose record bank manager Reiffenstein was said to have equalled. The professional golfer’s name may not even have been remembered.

Figure 15 Canadian Golfer celebrated Keffer's achievements in golf with this captioned photograph in 1919.

By 1920, however, when Secretary-Treasurer Tom German wrote to inform Canadian Golfer of the election results at the Napanee Golf Club’s annual meeting that May, he deemed it worth pointing out that a man who had subsequently won two Canadian Open championships, and who had just tied for second in the 1919 Canadian Open with an amateur from Atlanta named Bobby Jones, was the Napanee Golf Club’s course record holder. By now, the once unremarkable pre-war, pre-1909 scoring record by a no-name assistant professional from the Cumming shop was very remarkable, indeed: Karl Keffer had since made quite a name for himself!

Perhaps German was the only one who not only remembered Keffer’s feat, but also remembered his name.

More than ten years after the record was set, it seems that the Napanee Golf Club wanted to get out the word: the Napanee Golf Club has an interesting course where Canadian Open champions play!

Of course this argument that Karl Keffer was the professional golfer whose course record Reiffenstein was said to have equalled assumes that the 1914 announcement in the newspaper was incorrect in claiming that George Reiffenstein’s score of 39 had tied the professional course record.

Reiffenstein’s 39 was no doubt a new amateur record, but we have very good reason to believe that the professional record was in fact 37. This professional record – ostensibly set seven years before Reiffenstein’s magnificent performance in 1914 – had presumably simply been misremembered by the club member who reported Reiffenstein’s feat to the newspaper.

Alternatively, German may have misremembered Reiffenstein’s score from so many years before – turning a 39 into a 37.

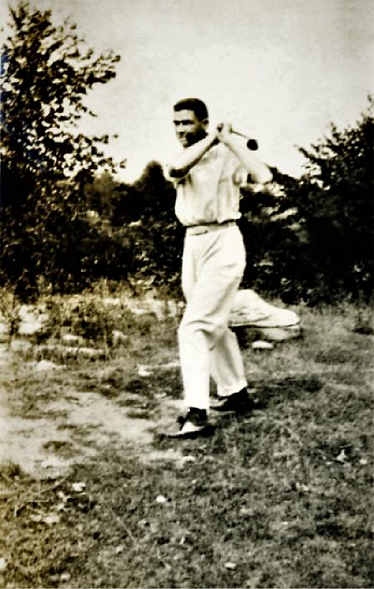

Reiffenstein's Amateur Course Record

As we know, in one of his last rounds of golf before he joined the Canadian Expeditionary Force and went overseas to serve in France during World War I, George Patten Reiffenstein shot the best score ever recorded by an amateur at the Napanee Golf Course.

Under the headline “New Amateur Golf Record,” the Napanee Beaver reported as follows on September 11th, 1914 (five weeks into the war): “Mr. G. P. Reiffenstein made a new amateur record for the local golf links on Wednesday afternoon. His score was a follows: 5, 3, 4, 4, 4, 5, 5, 5, 4 – 39.”

Here is how that score translates to the scorecard.

Figure 16 George Patten Reiffenstein's Napanee Golf Club amateur course record set in September of 1914.

Reiffenstein’s score was one stroke under the Bogey score.

Of course the par score for the 1907-27 golf course according the USGA standards as of 1911 would have been much lower (33).

1907 First Hole

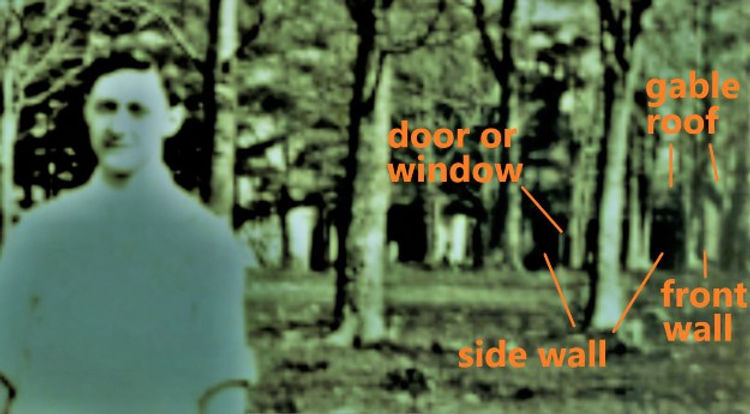

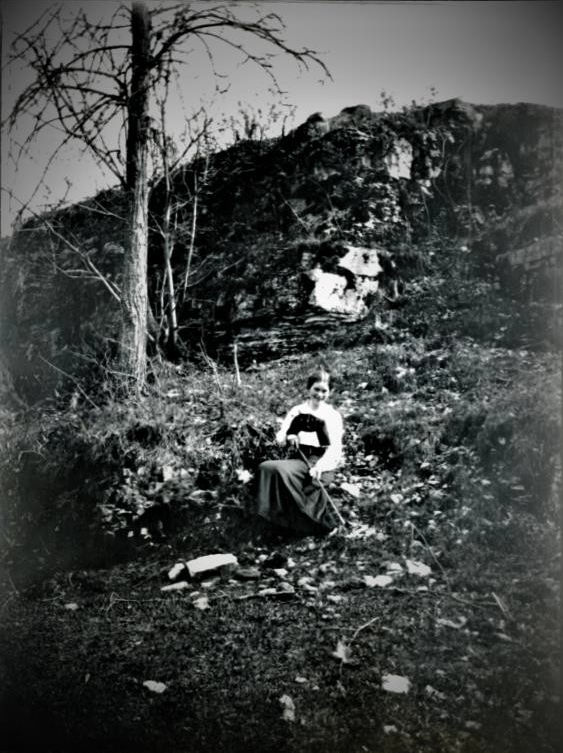

We have a photograph from the fall of 1912 of Caroline Herrington standing with her golf clubs on the first tee of the 1907 golf course.

Figure 17 Caroline Herrington indicates in her photograph album that this photograph was taken in the fall of 1912 on the first tee. Photograph N-08927. Courtesy of the County of Lennox and Addington Museum and Archives.

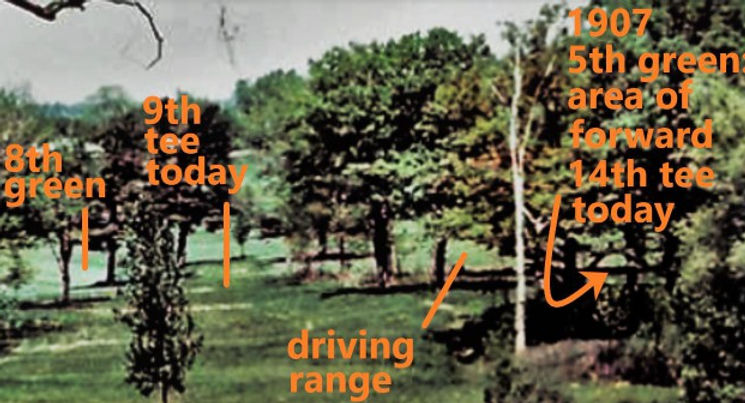

She stands in the area of some of the present tees on our ninth hole. Behind her is the stand of trees that has always grown between today’s eighth green and ninth tees. Through the trees behind her is visible the area that today serves as a driving range. The horizon of the land running through the middle of the photograph is constituted by the railway tracks on the east side of the golf course. The bare ground at her feet may mark the approach to a footbridge over the south creek that runs from the east side of the golf course through a gully all the way to Original Road (or Blanchard Road) not far from where she stands. I am guessing that because of the concentration of foot traffic at the approach to such a bridge, the ground immediately in front of it may have been worn bare.

Note, incidentally, that we see in this 1912 photograph not the fourteen-year-old novice with only a putter and a broken shaft in her golf bag that we saw in the 1906 photograph studied in Volume Two of this book, but a twenty-year-old golfer with a golf bag containing the six clubs that were regarded as the norm for a properly equipped golfer of the time.

The photograph below presents a cartoon image of a figure standing in the place today where I think that Caroline Herrington stood in the fall of 1912 at the first tee of the 1907-27 golf course. There is no sign that she was standing on the actual tee of the first hole – no chalk or whitewash outline of a teeing ground, no container of sand for making the tee – but she was in the general vicinity of the tee box.

Figure 18 Caroline Herrington indicated in her photograph album that the photograph of her on the golf course in the fall of 1912 was taken at the first tee. I believe she was standing near the area marked by the figure drawn above.

The scorecard indicates that the first hole was 347 yards in length. The green, therefore, must have been at the very top of Blanchard Hill. The Bogey score of five suggests that the hole was difficult.

We have a photograph from 1906 of “Mr. Bennett,” Caroline Herrington, and “Mr. Hall” standing on top of Blanchard Hill in the area where the first green of the 1907-27 golf course must have been located. The photograph was taken by Mary Vrooman.