CONTENTS

Making the Acquaintance of Colonel Bogey

Royal Wimbledon’s Professional Bogey Man Comes to Ottawa

An October Day of Bogey and Par at Ottawa

An Ambassador of the Dolemans’ Par

Ottawa Reactions to Colonel Bogey?

More News of Bogey at Montreal

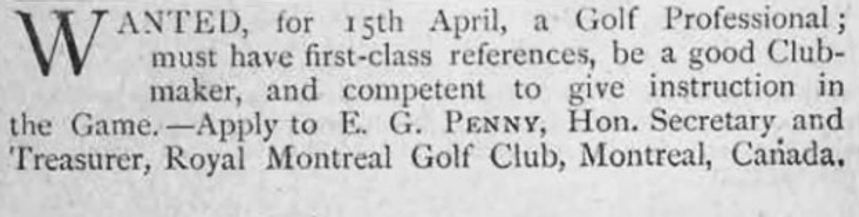

A Bogey Man for Montreal in 1894

Colonel Bogey’s Birds of a Feather

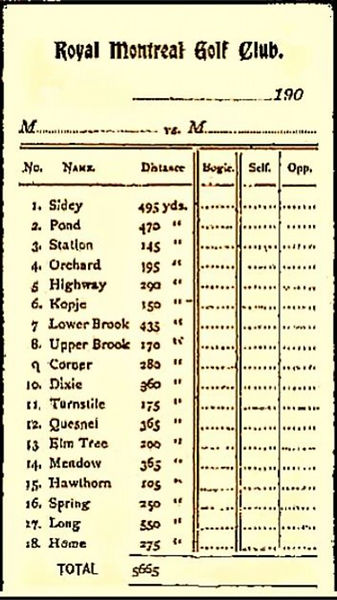

Royal Montreal’s First Year of Bogey

Another Use of Bogey at Montreal

And Who Was the Niagara Bogey Man?

Afterword: Irreconcilable Differences between Bogey and Par

Appendix I: Tom Smith Post-Montreal

Appendix II: Arthur Smith Post-Toronto

Introduction

In the spring of 1893, as the Ottawa Golf Club prepared to begin its third season after its founding in April of 1891, we learn from the newspapers of the competitions that the club had scheduled for the coming months:

The season’s matches include weekly handicaps with prizes, semi-monthly competitions to decide the championship and the holding of the Gilmour Cup, a valuable cup donated by Col. Allan Gilmour, and a “Bogey” competition. (Ottawa Free Press, cited in the Montreal Star, 2 May 1893, p. 5)

This item appeared in the Montreal Star, but it was reproduced from a report in the Ottawa Free Press. And the information contained in this item was no doubt supplied to the Ottawa Free Press by the Secretary of the Ottawa Golf Club, Alexander Simpson.

Figure 1 Alexander Simpson, Letter to the Editor (inviting British golfers visiting the Chicago World’s Fair to play golf in Ottawa), Golf [London], 12 May 1893, p. 154.

Simpson was vigilant throughout the 1890s in keeping the Ottawa newspapers informed of developments at the Ottawa Golf Club, and in the mid-1890s he also communicated club news and information to British publications such as Golf (London) and the Golfing Annual.

He no doubt put the word “Bogey” in quotation marks in acknowledgement that the word was a neologism: he was indicating that the familiar old word “bogey,” which meant “an evil or mischievous spirit,” or “a person or thing that causes fear or alarm,” was being used in an entirely new way in relation to golf.

The Ottawa Free Press simply presents the information it received from Simpson (perhaps verbatim) and offers no explanation of the term. It probably could not do so: this was the first time that the word had been used in this way in a North American newspaper.

Late in 1891 in England, the word had been used for the first time in history to indicate a new form of golf. The idea of “’Bogey’ competition” had caught on at several golf clubs in the south of England by the spring of 1892. Then it advanced northward through English golf clubs during the 1892 season. It reached a golf club in the north of Ireland in mid-summer, and it reached Scotland in the fall. “’Bogey’ competition” became known fairly widely in British and Irish golf clubs only by the spring of 1893, when the Ottawa Golf Club became the first in North America to make acquaintance with it.

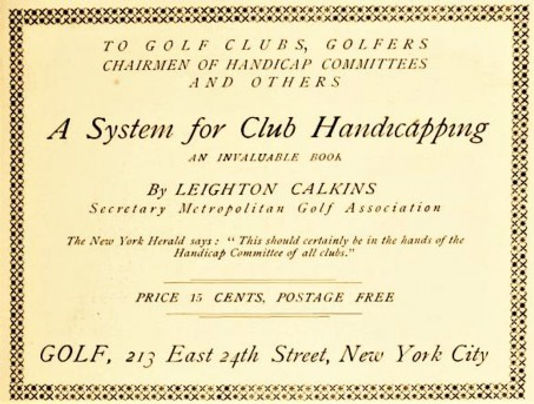

In the United States, the first use of the word “Bogey” in relation to golf appeared in newspaper and magazine reports only late in the summer of 1894, but not – as in the Ottawa newspaper – in relation to “a ‘Bogey’ competition.” The word merely referred to scores achieved on golf holes (see Vogue, vol 4 no 7 [16 August 1894], p. C3 and Outing: An Illustrated Monthly Magazine of Recreation, vol 24 no 6 [September 1894], p. 173). There is no reference to Bogey competitions being played at American golf clubs until 1895, and references to Bogey competitions merely caused confusion, as the editor of Outing observed in August of 1895: “The puzzling ‘Bogey’ is exercising the wits of some of our correspondents, who fail to find an explanation in the ‘glossary’ of the so-called practical textbooks, one of which is just off the press. ‘What is the bogey man?’ is the query we have been called upon to answer” (Outing, vol 26 no 5 [August 1895], p. 11).

And yet the word “Bogey” appears in the spring of 1893 in a Canadian newspaper’s account of the schedule of competitions for 1893 at the Ottawa Golf Club. The club had introduced an innovation to golf in North America. The editor of Outing could have directed his correspondents to the Ottawa Golf Club for an answer to their question, “What is the bogey man?”

The ripples from the invention of Bogey would prove to be among the most far-reaching in the history of golf in general, and Ottawa’s introduction of the concept to Canada in 1893 would have far-reaching consequences in terms of the golf professionals hired by Quebec and Ontario golf clubs in the 1890s and in terms of the improvement of the quality of golf played in Canada during that decade.

Engaging with the concept of Bogey in the spring of 1893, the Ottawa Golf Club was the first into the field in what would become a decades-long battle between Bogey and par for the hearts and minds of golfers regarding which term would be chosen to name the perfect round of golf.

A Bogey Par?

As we know, the word “Bogey” had been introduced to golf in England less than two years before it was used in Ottawa. And, as we shall soon see, it became associated with one of the most important concepts ever developed in golf – the idea of a proper score for a golf hole (and thereby a proper score for a complete round of eighteen holes).

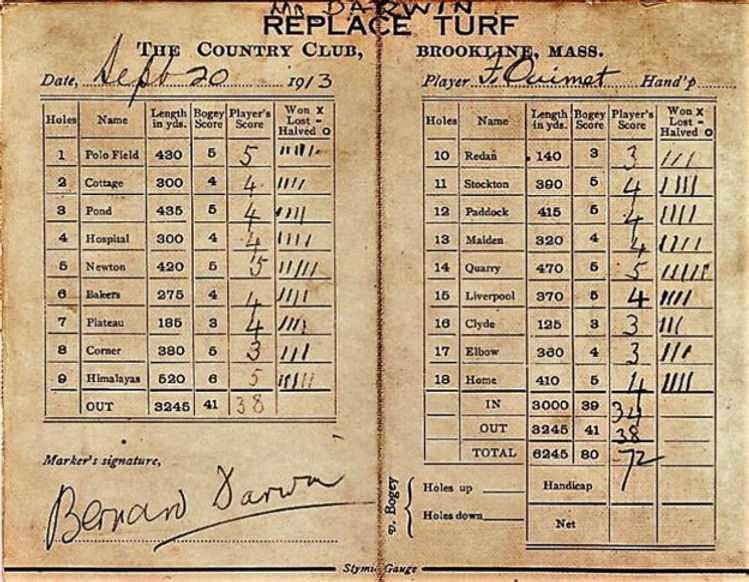

We now call this score “par,” but in the 1890s it was more often called the “Bogey” score than the “par” score, and a preference for Bogey over par endured well into the twentieth century. For instance, when twenty-year-old amateur Francis Ouimet defeated Harry Vardon and Ted Ray for the U.S. Open Championship of 1913 at Brookline, Massachusetts, British golf writer Bernard Darwin marked Ouimet’s score on an official scorecard that indicated a Bogey score for each hole, rather than a par score.

Figure 2 Francis Ouimet’s scorecard in the playoff with Harry Vardon and Ted Ray, 20 September 1913.

The same preference for Bogey over par endured in Canada well into the 1900s.

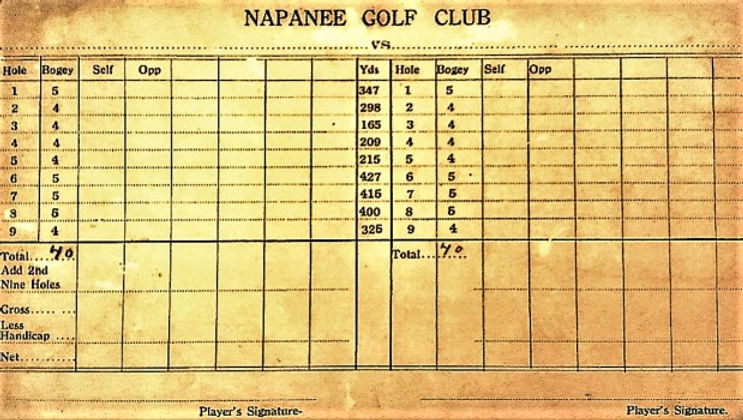

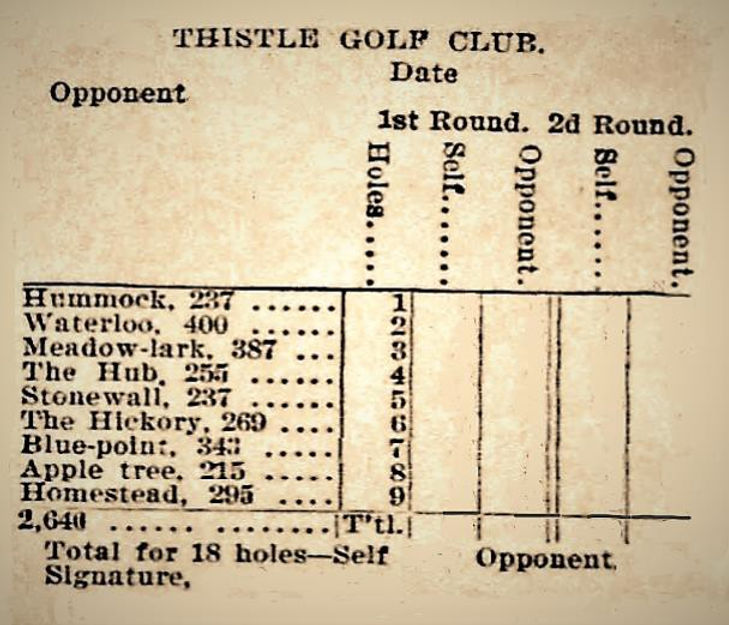

See below the scorecard for the nine-hole course of the Napanee Golf Club in the early 1900s.

Figure 3 Undated scorecard for the 1907 design of the nine-hole golf course of the Napanee Golf Club, a course in play from 1907 to 1926.

Although the concept of par preceded the concept of Bogey by twenty years, the latter initially prevailed.

Two decades after its invention in 1870, the concept of “par” had still not caught on with golfers, but when the concept of Bogey was invented in 1891 (in support of a new form of competition that it enabled), it immediately became more famous and more popular than the concept of par had ever been.

Ironically, however, the elastic way in which the concept of Bogey came to be used differently from one golf club to the next soon created problems for golf that only a reinvigorated concept of par could solve.

Ultimately, during the early decades of the twentieth century, all golf clubs – from the great Country Club at Brookline to the modest Napanee Golf and Country Club – would convert to par. The fate of Bogey would be to name a score on a golf hole of one more than par.

Oh, the ignominy!

The Invention of Par

For the first 500 years of golf history, there was no such thing as a par score for a golf hole or for a golf course. The goal of the golfer was simply to take as few strokes as possible to complete a golf hole and, in turn, a golf course: for neither a golf hole nor a golf course was there recognized a theoretically proper number of strokes that a first-class golfer should take in completing them.

Figure 4 Scorecard of Young Tom orris for rounds one and two of the 1869 Open Championship at the Prestwick Golf Club in Scotland.

Note the photograph to the left, for instance, which shows the scorecard of Young Tom Morris for the 1869 Open Championship on the twelve-hole links of the Prestwick Golf Club in Scotland: it simply lists by number the twelve holes to be played, with no par score indicated for any hole.

Young Tom won the three-round championship by eleven strokes, his second win in a row, and in doing so he recorded the first hole-in-one in Open Championship history on the eighth hole during the first round (as recorded on the scorecard shown to the left).

At the next Open Championship in 1870, another first occurred in golf history when the word “par” was used in reference to a golf score in a discussion amongst some of the top competitors who had returned to the same Prestwick course to battle again for the Championship Belt.

Top amateur players of the day, Alexander Hamilton Doleman and William Doleman, along with younger brother Frank, were sharing a cottage at Prestwick with Scotland’s top three professional golfers: Jamie Anderson, Davie Strath, and Young Tom Morris. It was assumed that one of these three accomplished young professionals would win the championship, Young Tom having won the previous two.

Talk amongst the housemates turned to the question of what the professionals thought the winning score would be. American golf writer Charles Quincy Turner summarizes the conversation that ensued:

Figure 5 David Strath (1849-79).

Davie Strath, Jamie Anderson, Tom Morris, Jr., and the brothers Doleman were staying in the same cottage, when naturally they fell to discussing what score ought to win on the morrow. Some said one thing, some another. At length William Doleman, so says his brother A.H., asked Davie Strath and Jamie Anderson what a certain hole should be done in, if played correctly.

Davie Strath gave the required number at once.

Figure 6 James Anderson (1842- 1905).

Figure 7 William Doleman, 1880.

“Ah!” says Jamie Anderson, “that’s a’ very guid, but what about a bad lyin’ la’?”

“Tut! Tut!” says Davie, “that has naethen’ tae dae wi’ it, Jamie; that’s the number you should do it in.”

And Davie laid great stress on the “should.”

By degrees M[r]. W. Doleman led the professionals on to give the “should” for all the other holes.

And this ideal, or perfect, round was found to be 49 for the twelve holes.

And then says Davie, “That is the number we should do it in, if we play perfect golf, but I know we won’t do it.”

While Davie was still talking, in walked Tom Morris, Jr.

And hearing what Strath was saying, he shook his head, smiled, and then said, “We’ll hae to try ony how.”

Figure 8 Young Tom Morris (1851-1874).

And Young Tom did try, and made a noble effort, coming within two strokes of perfect golf by holing the thirty-six holes in 149 strokes, very nearly an average of fours.

Mr. A.H. Doleman, thinking it would be a good thing to have some word to indicate the required number of strokes for a hole, and so for the whole round, on an infallible principle, chose the word “par.” (Golf [New York], vol 14 no 2 [February 1904], p. 100).

Figure 9 A.H. Doleman, circa early 1890s.

A.H. Doleman had chosen the word “par” for the number of strokes that a hole should normally take because this number struck him as analogous to the price used to indicate the “par” value for a stock certificate.

A corporate charter indicates the original or nominal value of shares issued for purchase. In the stock market, however, shares may sell for a price higher or lower than the “par value.”

Similarly, golfers can make a score on a golf hole higher or lower than its “par value.”

The Par Brothers Doleman

William Doleman (1838-1918) had easy and familiar access to Scotland’s top golf professionals because he was an elite amateur player who regularly played against the professionals in medal-play tournaments or played with them in foursomes match-play competitions.

He had played against Jamie Anderson and other top professionals in an important tournament in Montrose in 1866, and he had defeated them all. He played against Young Tom Morris at another important tournament at Carnoustie in 1867 (a tournament open to professionals and amateurs, which the precocious sixteen-year-old Morris won in a playoff).

William Doleman also played against Young Tom, Davie Strath, and Jamie Anderson in the Open Championships held at Prestwick from the mid-1860s to 1870. After each of these competitions, all four players engaged with various partners in exhibition matches at Prestwick.

Figure 10 Contemporary aerial photograph of the Musselburgh Links Golf Course located within the Musselburgh racecourse.

Doleman had learned to play golf at Musselburgh. The city’s nine-hole course along its main street would become one of the most important in Scotland, hosting six Open Championships between 1874 and 1889. As it still does today, the golf course played into and out of the infield of the Musselburgh racecourse.

Doleman’s father, also called William, was at first a tailor, but he became in 1838 the Race Stand Attendant at the Musselburgh racecourse, and so he also looked after the “boxes” (a form of locker) that were rented by club members. His sons were allowed to play on the golf course, and they all did so with enthusiasm.

The youngest brother, Francis (“Frank,” 1848-1929), was the only one to become a golf professional. In the 1860s, he worked at both golf clubs on the Wimbledon Common (the London Scottish Club and the Royal Wimbledon Club). Then he returned to the Edinburgh area, working a short while as a golf professional before becoming manager (and then owner) of a club-making business.

Figure 11 John Doleman, Golf Illustrated, vol 2 (20 October 1899), p. 41.

The oldest brother, John (1926-1916), settled in Nottingham in 1884 and founded the Notts Golf Club. He was the only brother not to play in an Open Championship. Mind you, he was present at the Open Championship of 1870, although not as a competitor. Instead, he played with his three brothers in the exhibition matches at Prestwick held the day after Young Tom’s victory: “John Doleman and William Doleman played a match of two rounds (24 holes) against A. Doleman and F. Doleman. John and William won by one hole” (Glasgow Herald, 17 September 1870, p. 3).

By far the best golfer among the brothers was William, but he was also the one with the greatest wanderlust: “Willie” became a sailor when he was fifteen, determined to see the world.

And so he did.

Figure 12 William Doleman, circa 1898.

In 1854, he was on a British ship that participated in the bombardment of Odesa on the Black Sea at the beginning of the Crimean War.

As he always took his golf clubs with him on his sea voyages, during the two weeks he was in port at Quebec in 1859, he set up a makeshift golf course on Cove Field on the Plains of Abraham and played many a round over it.

He returned to Scotland in the 1860s. After winning a prestigious tournament on the Montrose Links (a tournament that included professionals Old Tom Morris, James Anderson, and Bob Kirk), he told astonished organizers that he “drives a baker’s van in Glasgow every day” (Golfer’s Yearbook for 1866, ed. Robert Howie Smith (Ayr, Scotland: Smith & Grant, 1867), p. 72). He afterwards became a cab driver in Glasgow, eventually owning his own cab hire company.

As a member of Prestwick’s St. Nicholas Golf Club, he pursued golf with a passion, becoming in 1865 the first amateur player to enter the Open Championship. He went on to post the lowest score by an amateur every year from 1865 to 1872. Becoming a member of the revived Glasgow Golf Club in the mid-1870s, he also posted the lowest score by an amateur in the Open Championships of 1875 and 1884. His best finishes in the overall standings were third, fifth (twice), sixth (twice), and seventh. In 1872, only Young Tom Morris and Davie Strath beat him. In an exhibition match at the 1876 Open championship at St Andrews, Doleman played against the 1874 champion Mungo Park and beat him by one hole (Field, vol 48 no 1241 [7 October 1876], p. 422). He would play in the British Amateur Championship until 1912, when he was seventy-three years of age. When he died in 1918, Field described him as “the finest amateur golfer of his day” (cited in The Transcript-Telegram [Holyoke, Massachusetts], 12 August 1918, p. 5).

Although William had been the one whose close questioning had elicited the principles of par golf from the professional golfers, it was his brother Alexander who became the one most closely associated with the articulation and promotion of the concept of par if for no other reason than that he was the one who became a writer and contributed essays on the subject of par to the golf journals of the day.

Figure 13 A.H. Doleman, circa early 1890s.

Alexander Hamilton Doleman (1836-1914) was from the beginning the most academically inclined of the four brothers. He attended the Bridge Street Academy in Musselburgh, graduating as one of the top students. Whereas his younger brother William was eager to leave school as soon as possible, Alexander could hardly get enough of it. So, the son of Musselburgh’s Race Stand Attendant and keeper of the golf club lockers took a degree at the University of Cambridge.

Determined to become a teacher, Alexander moved to Blackpool in the late 1850s to set up his own private school.

Still in love with golf, but finding no golf courses in the area, for five years A.H. Doleman played golf alone on the sand dunes along the seacoast of the Irish Sea near Blackpool, forced to set up his own makeshift golf course.

Finally, four local gentlemen joined him, overcome with curiosity about what he was up to, and soon thereafter founded with him (along with fifteen others) the (now Royal) Golf Club of Lytham and St Anne’s (regular host of the Open Championship). Doleman became perhaps the most important person in the club over the next four decades and was honoured in due course as “a Father of Fylde Golf” (as seen above in an image from a local publication celebrating his influence on the Borough of Fylde in Lancashire).

In 1870, William Doleman had worked hard to winkle out of the professional golfers at Prestwick the principles by which to determine the number of strokes in which a golf hole should be done, and A.H. Doleman’s invocation of the word “par” to denote the accomplishment of this feat was inspired.

Yet progress in the use and understanding of this term was slow and fitful for the next twenty-five years.

Early References to Par

The Doleman brothers continually used the word “par” themselves, working out the par score for every golf course they played, and explaining the concept of “par golf” to anyone who showed the slightest curiosity about it. And they continued to ask professional golfers what they thought the par score should be for various golf holes and golf courses.

The word “par,” however, appears infrequently in newspapers and golf journals from the 1870s to the early 1890s. And we can see that among those who used the term there was not a common understanding of what it meant.

In 1879, we read in The Scotsman a report of a competitor at St Andrews who “was unlucky in running up an awkward 6 at the first hole, where 4 is par play” (8 May 1879, p. 7). There is no ambiguity here: par is four. Also in 1879, however, we find a report of a match at Musselburgh in which a competitor does well, “notwithstanding a very bad seven run up at … [a] hole for which the ‘par’ play was no more than four” (The Field, vol 54 no 1,400 [25 October 1879), p. 571). Here there is ambiguity: it seems that “‘par’ play” is relatively elastic, as it might be four, or it might be three.

The phrase “par play” was used more frequently in the 1880s.

Figure 14 Early golf at Seaton Carew, County Durham, England.

One of Field’s correspondents in 1883 reports on the new golf course of the Durham and Yorkshire Golf Club “at Seaton Carew, near Hartlepool,” observing that “the green consists of eleven holes only” and that “Par play for the eleven holes would be 58” (vol 61 no 1584 [5 May 1883], p. 596). And later the same year, a writer in The Newcastle Daily Journal describes the golf course at Earlsferry, Scotland, as “a second-class course only … on which par play means an average of 3 ½ strokes to each of the twelve holes” (4 December 1883, p. 4).

For these writers, par seems to be a fixed standard of play. Still, others continued to use it in a more elastic way.

In the spring of 1882, for instance, a writer from North Berwick tells of a remarkable round of golf played there in windy conditions and suggests that a “par” score should be understood not as a fixed standard but rather in relation to the conditions prevailing on the day:

The weather on Saturday was not conducive to brilliant work, for, although dry overhead, there was a strong east wind, which had an aggravating tendency to materially contribute toward heavy totals when cards were handed in…. Strange to say, none of the scratch men were ever dangerous, the trophy being carried off by Major Hay with a total of 85, and a net score of 79… [T]hat a player who received 6 [strokes] … should, under the wind disadvantages, negotiate it in 85 strokes is of itself a fact worthy of note. It is undoubtedly a “par” score, and the best testimony of its merits is the distance it is ahead of the totals of such experts as Messrs Whitecross, Bloxom, and Chambers, all of whom were in good playing form. (The Field, 8 April 1882, p 474)

The writer has heard of the concept of “par” scores, but if Davie Strath were to have heard him suggest that the day’s windy conditions had anything to do with determining the “par” score for the course, he would have said: “Tut! Tut!... That has naethen’ tae dae wi’ … the number you should do it in.”

In 1887, when A.H. Doleman himself used the phrase “par play” to report in Field on a competition at the Lytham and St Anne’s Golf Club, a reader signing his letter “an old golfer” later wrote to the editor to ask what on earth was meant by the phrase “par play”:

I was rather amused on reading an account of the meeting of the Lytham and St. Anne’s Golf Club in your issue of Saturday last. Your correspondent speaks of the par play of that green. What does he mean by this?

Is it the lowest score it is possible to do the round in, bar mistakes, bad play, bad luck, etc?

It is very easy matter to decide what number of strokes a course can be done in when you are sitting by the fireside with a pencil and a piece of paper in your hand.

As an example of what a hole might be done at, take the first hole at Hoylake. Last autumn, my partner started with a long drive off the tee and followed this up with another right on the putting green within about three club lengths of the hole, but, unfortunately, missed the ‘put’ for a three, and also his next, therefore taking five to hole out – a very fair number after all.

Would your correspondent say that three strokes was the ‘par’ of this hole? (Field, no 1887 [9 April 1887], p. 478)

Doleman replied with equal parts incredulity, condescension, and disdain:

Where is the “old golfer” who does not know what the par play of a green is?...

Every good golfer knows what a first-class player ought to do a hole in ….

[P]ar does not mean what a hole can be done in. As an example, the Rushes hole at Hoylake can and is sometimes holed in one stroke, but most certainly that is not the par of the hole. The par is three.

Again, the first hole is seldom driven in two strokes, unless by exceptional drives, consequently five must be taken as the par. (Field, no 1792 [30 April 1887], p. 606)

Doleman is rather hard on the person who signs his letter, “old golfer.” That “Every good golfer knows what a first-class player ought to do a hole in” does not mean that every good golfer knows that the phrase “par play” was coming to be used to describe the accomplishment of this feat. Doleman’s tone perhaps reveals a frustration that, seventeen years after his invention of the term “par,” it is still only the golf world’s cognoscenti who understand the term and use it properly.

Yet the more the word appeared in print, the more occasions there were for readers like “old golfer” to enquire of editors just what the word meant. And however slowly, such curiosity helped the use of the term to spread.

Par? What Is It Good For?

The most important factor in keeping the concept of par from gaining popularity was that it had no practical implications for the playing of the game.

Golf culture in Scotland had from the beginning understood match-play to represent the essence of the game. Contests among members of golf clubs were conducted by match-play. Team contests between golf clubs were conducted by match-play. The nineteenth century’s many famous, high-stakes matches between the top professionals were conducted by match-play (before hundreds – and sometimes thousands – of spectators).

Figure 15 Photograph circa 1854-55 commemorating a match-play contest involving Willie Dunn (addressing ball), Willie Park (to his right, watching him), Allan Robertson (club on shoulder), and Tom Morris (holding one club, right hand on grip, left hand on head). Ranged behind, left to right, are caddies James Wilson, Bob Andrew, D. (“Daw”) Anderson, and Bob Kirk.

Match-play required no concept of par, and it gained nothing from it.

Medal play was regarded as a necessary evil – a departure from match play made necessary by a large field of competitors: medal play was merely a practical and convenient way of determining a champion from a large number of players in a much shorter time than match-play among them would require.

Obviously, since the winner was the one who completed the course in fewer strokes than any other competitor, medal play also required no concept of par, and it gained nothing from it.

And the idea of using a universal standard of par as the basis for handicapping golfers would not occur until the late 1890s and early 1900s, and only then because the concept of Bogey had shown both how such a system of handicapping might be possible and why it might be necessary!

And so, for the first twenty-five years of its existence, the concept of “par” seemed to be literally useless

The Relative Uses of Par

And so, having brought the concept of par into being, the Doleman brothers struggled to find a use for it.

For the better part of three decades, they were happy to argue that it had a “relative” use: that is, it was useful in comparing golf courses. One could relate the test posed by a golf course with a par value of x to the test posed by another golf course with (say) a par value of x + 2 or, perhaps, a par value of x – 3, etc.

Although William Doleman became associated with the Glasgow Golf Club for more than four decades after its revival in 1870, before that he had been forced to travel to Prestwick to play golf as a member of the St. Nicholas Golf Club. In the latter’s club championship in February of 1871, held on the Prestwick links one year after Young Tom Morris’s record-setting score there in the Open Championship held in September of 1870, Doleman’s fellow club member James Hunter (who would introduce golf to Quebec in 1874) shot a score on the newly lengthened links that led to the implicit invocation of the concept of par in order to compare the performances of the two young stars:

Figure 16 Young Tom Morris, 1870.

The weather was most adverse to good play – a high wind and a drenching rain prevailing during the whole game.

The match consisted of two rounds of the Links, [or] twenty-four holes….

The club medal was gained by Mr. James Hunter, whose scores of 55 and 58, respectively, have rarely, if ever, been excelled, even by professionals.

The present round of the Links being four strokes longer than that [on] which the champion, [Young] Tom Morris, carried off the belt in September last, makes the success of Mr. Hunter all the more remarkable. (Glasgow Herald, 21 February 1871, p. 6)

Although the word “par” was not used in the passage above, the newspaper report noted that the course had been made four strokes longer in the five months between the rounds of Morris and Hunter. Doleman’s method of using the length of a hole to determine the number of strokes it should take to complete a hole is responsible for this calculation of precisely how many strokes longer the Prestwick links had been made by its redesign.

Note that Doleman, who had prompted the invention of par through his conversation with the young professionals at the Prestwick Open championship the previous September, may have been the only club member who knew what the professionals had determined to be the par of the course a few months before. And he was probably the only one who knew the distances that they had decided were appropriate for par-three, par-four, par-five holes. Furthermore, Doleman was Hunter’s playing partner during the round in question. One might suppose that Doleman was the source – if not the author – of the newspaper report cited above that compares the two versions of the golf course in terms of their relative pars.

Similarly, when in 1881, Glasgow Golf Club member Andrew Whyte Smith won the Tennant Cup for the second year in succession, in a tournament that was effectively the British amateur championship at that time, the Glasgow Evening Post indicated the quality of his play relative to par play:

Figure 17 A.W. Smith, 1880.

Last year, the first occasion on which the cup was played for, Mr. A.W. Smith was the winner, and Mr. Smith and his partner, Mr. Finlayson, of Edinburgh, had a large following on Saturday.

Mr. Smith was in magnificent form. He started with a couple of threes, each of the holes being well taken at four, and the round of nine holes, the par of which is 39, he finished at 40.

The second round was gone over in an almost equally faultless manner at 41 …. His total of 81 was an excellent performance…. When all the cards had been handed in, it was found that Mr. Smith had carried off the cup for a second time. (Glasgow Evening Post, 25 April 1881, p. 4)

William Doleman was a regular playing partner and personal friend of Smith’s from the moment Smith joined the club in 1874 to the day he left for Canada in May of 1881. Doleman was undoubtedly responsible for the fact that talk of the par score at the Glasgow course became a commonplace.

This use of par to assess the relative difficulty of golf courses began to spread.

In the late 1880s, for instance, discussion of Old Tom Morris’s work at Dornoch occasioned wider understanding and use of the word “par”:

The present course of eighteen holes was laid out by Tom Morris in the spring of 1886. We all know what Old Tom can do in this way, and his skill has not failed him at Dornoch. The par of the green is seventy-one strokes, and this will give all golfers an idea of what they could do upon it. For those who do not know what par play means, a word of explanation may be given. Take a first-class player, and then any hole he can drive in one should be holed in three. If it takes him two long shots and an iron stroke to be on the green, then the hole should be finished in five, and so on. (Fifeshire Journal, 12 September 1889, p. 2).

According to the editor of the Fifeshire Journal, after being instructed as to the meaning of par play, golfers informed of the par score of a particular golf course should be able to estimate the challenge that it will pose for them.

Figure 18 D.S. Duncan, early 1900s.

A year later, in the third volume of the Golfing Annual, which covered the years 1889-90, the journal’s new editor, David Scott Duncan, noting that the Dornoch golf course was about to be redesigned by Old Tom Morris, also observed that “The par of the green is seventy-one” strokes” (p. 31).

And, like the editor of the Fifeshire Journal, Duncan knew that he had used a word and invoked a concept that even most of the dedicated and knowledgeable golfers who read his specialized golf publication would find unfamiliar.

And so, we find him apparently borrowing word-for-word the passage above from the Fifeshire Journal:

For those who do not know what par play means, a word of explanation may be given. Take a first-class player, and then any hole that he can drive in one should be holed in three. If it takes him two long shots and an iron stroke to reach the green, the hole should be finished in five, and so on. I believe this method of calculation was invented by my good friend, Mr. William Doleman, one of the best authorities on all points of the game. (Golfing Annual for 1889-90, p. 31)

Editor Duncan did not use the word “par” again until he had occasion to discuss the completion of the Dornoch redesign two years later: “Following the suggestion of Tom Morris the course was considerably lengthened last year …. With this extension, the par of the green is raised from about 72 to 78 strokes” (Golfing Annual for 1891-92, p. 135).

Figure 19 William Doleman, American Golfer, vol 9 no 4 (February 1913), p. 386.

In 1896, William Doleman hit upon the idea of using the concept of par play on different golf courses to compare the achievements of great golfers of different generations.

At the Open Championship held at Muirfield in 1896, Doleman had objected to claims by journalists and professional golfers alike that the play at this tournament had been superior to championship play by golfers of previous generations.

He was convinced that such claims were incorrect. But was there a way to disprove them by means of an objective recourse to facts?

Doleman immediately hit upon the idea of using the score for par play on different golf courses as a factual constant against which the play of golfers from different generations could be measured and compared.

He used this strategy to argue that no golfer’s performance relative to the par score of Carnoustie in 1896 had matched the performance of Young Tom Morris relative to the par score of Prestwick in 1870 (a performance that Doleman himself had witnessed):

There isn’t a man, English or Scotch, in all this field that impresses me with the same sense of power, or golfing genius, call it what you like, as Tommy did, the instant he addressed the ball….

But they tell us he had nobody to play against.

That’s nonsense, for he had Davie Strath, Bob Ferguson, Jamie Anderson and other notable golfers; but supposing he hadn’t, he had always the ideal, the “par” score of the green to play against.…

It is there we get at Tommy’s position in the golfing world of today …. (quoted by William Weir Tulloch, The Life of Tom Morris [London: T. Werner Laurie, 1909], pp 170-71).

Doleman had appreciated at the Glasgow Golf Club in 1881 his friend A.W. Smith’s record score relative to the “the ideal, the ‘par’ score of the green,” but in 1896 he proposed to compare Young Tom’s 1870 Prestwick score relative to the par score of that links to the best Muirfield scores relative to the par score of this new links.

Doleman proceeded to calculate the par score for Muirfield (“Mr. Doleman’s own calculation, and that of some professionals with whom he had discussed the question,” was 74 [cited by Tulloch, p. 172]), and then he pointed out that the best score at the relatively new Muirfield course for the thirty-six holes of the 1896 Open Championship was seven over par, whereas for the thirty-six holes of the 1870 Open Championship at Prestwick, the score of the winner Young Tom Morris was only two over par.

Doleman was left with one conclusion: “Some of these moderns are grand golfers, no doubt, but the more I think out these things, the more I am convinced of Tommy’s surpassing greatness, and the better am I able to vindicate his superiority against all comers” (quoted by Tulloch, p. 173).

Doleman’s vindication of Young Tom as the greatest golfer of all time clearly depended on the concept of par.

Figure 20 A.H. Doleman, Golf [London], vol 6 no 50 (28 July 1893), p. 34.

Finally, in 1898, A.H. Doleman explained the concept of par play in the fullest and clearest terms yet.

In articles published at the beginning of the year, he promoted widespread calculation of par scores for all golf courses as the only way for golfers to assess the relative challenge they would face at the dozens of unfamiliar new layouts that were opening each year in the British Isles.

Twenty-eight years after the invention of par in the rented cottage at Prestwick, it was still necessary both to rehearse the basic concept and to anticipate the usual objection that since a hole could be completed in fewer strokes than its par score, then par could hardly be called the “ideal” score:

If we take a hole on any green, it may be a long hole, or it may be a short hole, every good golfer, when he has played it a few times, can tell what the hole should be done in, if he play it without mistake.

Should he take more than this number, from whatever cause, he knows that one or two strokes, as the case may be, have been lost. Should he take less, he knows again that he has done something which no amount of practice can give him any tolerable certainty of repeating….

Thus, when one holes a full shot with any club, everybody knows that no amount of practice will ever enable any golfer to repeat this with any amount of certainty. But more than this, no amount of practice will ever enable any player to hole in two strokes with any amount of certainty from a full drive, [and] a cleek or an iron approach.

Again, no amount of practice will ever enable any golfer to hole putts at any distance within twenty yards of the hole. A time may come when these shots will be looked for as what a first-class player ought to do, but it has not arrived just yet.

Having seen what is not to be expected from the first-class player, let us see what is expected.

In approaching a hole, whether it be by a full drive or the ordinary approach, it is expected from a first-class player that he shall be somewhere on the green. Being on the green, he ought to be dead with his long putt, or so near as to hole in two, thus enabling to hole in three off the approach.

This is the standard now; and, looking back for a period of nearly fifty years, always has been the standard for first-class play.

Whether some of the many patents [for new types of golf clubs] coming out every day will so revolutionise the game as to enable us to hole in two off the approach with no more difficulty than we do now in three, I cannot say, but “I hae my doots.”

Seeing that three strokes is the requisite number from the approach, we have only to add the number of full drives in a hole before the approach, and the proper number of strokes for the hole is known. Thus, if a hole requires one full drive before the approach, it is a four-hole; if two drives, a five-hole, and so on. Of course, if the hole consists of only one stroke, be it a full drive or ordinary approach, it is a three-hole.

The word by which this number is known in the golfing world is called “par”; and when the totals of the different holes are added together, we get the par of the links.

When therefore we see a record from some green, especially if it is not well known, those who insert the record should take care to insert the par, for it is only by knowing the par that outsiders can judge the quality of the play [that produced the record score]. (Golf [London], vol 15 no 394 [28 January 1898], p. 354)

A.H. Doleman could hardly have made things any clearer: calculating par required a simple mathematical calculation. And this calculation would allow a relative assessment of the level of difficulty of all golf courses.

Resisting Par

In addition to benign neglect of the concept of par, there was also considerable resistance to the way the Doleman brothers conceived of par scores and par play.

First, the Dolemans’ method of determining par required a measurement of golf holes according to an implicitly straight line down the middle of a fairway, and then it required the measured distances to be divided by increments according to the driving distance of the first-class player (understood from 1870 to 1890 to be about 170 yards). This mechanical and mathematical approach put off those who saw golf as an art.

Second, the Dolemans’ golf course was implicitly one on which the sun always shone, and no more than heavenly breezes ever blew. On actual golf courses, however, drenching rain (or even snow) might fall, a gale might blow, and poor light conditions (even darkness itself) might impede scoring conditions. On a real golf course, the ground might be waterlogged or baked dry, and it was seldom level or flat: judging the distance to hit a shot was made difficult by hills and valleys, and mounds made bounces unpredictable. On the Dolemans’ course, furthermore, there seemed to be no hazards to be avoided. A par score was relevant only to a golfer sitting in an armchair dreaming of par play on an abstract layout.

Third, their method seemed to require a good deal of talk. As English golf writer W.L. Watson observed in Golf Illustrated in 1899 (a year after A.H. Doleman’s articles promoting par had appeared):

As for the par score: ah! What is the par score?

We all remember Mr. [A.H.] Doleman’s attempt to define it, dictated by an admirable spirit and having in view the best interest of the game; but it is to be feared that the impression he left was that the “par” of the green is only to be arrived at by an involved process of trigonometry and dialectics. (Reprinted in Golf [New York], vol 5 no 6 [December 1899], p. 398)

By “dialectics,” Watson alludes to the way Socrates developed the art of investigating or discussing the truth of opinions: Socrates would ask his students for their definitions of beauty, or love, or justice, highlighting contradictions and inconsistencies until through a process of corrections and qualifications a viable definition was arrived at. In just this way, William Doleman had dialectically elicited a definition of par from the professionals at Prestwick in 1870, and he had done so again from the professionals at Muirfield in 1896.

Should dialectics be required to determine par?

In 1889, Duncan, the editor of the Golfing Annual, had agreed with the editor of the Fifeshire Journal that the par of the Dornoch links that Old Tom Morris was about to redesign was 71, but when he looks back at the original course after the completion of Morris’s work in 1891, he says that the old par was “about 72” (Golfing Annual for 1891-92, p. 135). As Duncan thinks of the original Dornoch layout, his opinion of its par has changed. Similarly, assessing the new links at Muirfield, Duncan suggests in the Golfing Annual for 1892-93 that “the par of the round may be placed at about 72,” yet in 1896 William Doleman and various golf professionals would say that the par for Muirfield was 74 (Golfing Annual for 1892-93, p. 58). Opinions of Muirfield’s par differ.

Can par be a matter of opinion?

Should a hole on which two perfect shots could reach the green, provided the second shot were to clear a ditch immediately in front of the putting surface, be regarded as a par four? If, except under some dire necessity in a match, first-class players would seldom attempt such a dangerous second shot, preferring instead to play short of the ditch with the second shot and then play onto the green with a third shot, should such a hole not be regarded as a par five?

Is there an elastic element in measuring par?

Figure 21 Henry Stirling Crawfurd Everard (1848-1909). Golf Illustrated, 1 February 1901.

In an 1899 article about that year’s early golf events, widely-respected English golf writer Henry Sterling Crawford Everard looked ahead to the 1899 Open Championship at Royal St. George’s Golf Club in Sandwich, England, and opined that talk about the par score for the Sandwich golf course was neither here nor there: it was interesting only “if we accept Mr. A.H. Doleman’s estimate of perfect play” (Badminton Magazine of Sports and Pastimes [London], vol 8 no 4 [May 1899], p. 282, emphasis added).

His point was that the actual golf that would win the championship would require a mental measurement of actual distances and a mental gauging of actual conditions to produce actual physical shots and an actual score.

What had real golf got to do with an abstract and artificial “estimate” of perfect play?

Over the three decades after Bogey was invented in 1891, however, an “estimate” of something like perfect play on each club’s golf course increasingly became one of the most practically important questions to be decided at virtually every golf club in the world.

The Invention of Bogey

A year after Duncan’s first reference to the Dolemans’ concept of par in the widely read Golfing Annual, a similar concept emerged during the winter of 1890-91.

At this time, as Robert Browning points out in A History of Golf: The Royal and Ancient Game (1955; reprinted Pampamoa Press, 2018), the concept of a proper score for the golf ground of the Coventry Golf Club was determined by the club’s Secretary, Hugh Rotherham.

Figure 22 Hugh Rotherham. Golf Illustrated, vol 2 (22 December 1899), p. 283.

Rotherham had set himself the task of considering whether a way might be devised for a large number of club members to engage in match-play competition such that a winner might be determined after a single eighteen-hole round played by all contestants on the same day. As things stood up to 1890, if (say) sixty-four club members were to engage in a match-play tournament, it would take at least three days of matches, comprising two eighteen-hole rounds per day, to determine a winner.

Rotherham recognized that, in theory, were each contestant to engage in a match-play competition against the same golfer at the same time, their relative performances against this common competitor could be measured in terms of how many holes each of them had won or lost in battle with this person. In theory, the person who won the most holes from (or lost the fewest holes to) this common competitor could be declared the winner of that day’s competition.

Rotherham’s ingenious insight was that the common competitor requisite for such a contest need not be real: for each hole, a score could be recorded ahead of time as the score achieved by an imaginary person with whom each club member would then compete in the day’s match-play tournament.

What scores should be recorded ahead of time for this fictitious competitor?

Rotherham decided to attribute to this imaginary golfer not necessarily the score represented by what the Dolemans called par play, but rather the hole-by-hole scores that the club’s best golfers (who were in those days designated the club’s “scratch” players, regardless of whether they scored in the 70s, 80s, or 90s) tended to make at each hole, provided they made no serious mistakes. By February of 1891, he had worked out such scores for each hole of the Coventry golf ground, thereby determining what he regarded as a proper score for a complete round of golf as played by his imaginary golfer. He called this the Coventry “ground score.”

The first tournament that the Coventry Golf Club conducted based on each golfer’s match against the hole-by-hole scores recorded on this imaginary person’s scorecard occurred in the middle of May in 1891:

An interesting competition was played on the Coventry links on May 13th, for a handsome prize given by Mr. Hugh Rotherham. The scratch score of the holes had been fixed, and each player played a match against the ground score under handicap. The arrangement was found to be an excellent one, enabling a match-play competition to be finished in the day. (Golf [London], vol 2 no 36 [22 May 1891], p. 173)

As golf courses in those days were often called a “golf ground,” the phrase “ground score” was presumably a short-hand version of the phrase “the Coventry golf ground scratch score.” As a theoretically appropriate “score for the ground,” this score was analogous to a par score, and as a score against which players could measure their performance in competition, it was the first practical application of a concept related to par.

Less than a week after this innovative form of golf competition occurred, Coventry Golf Club member Harold Smith (who had finished third in the inaugural tournament) passed along news of the innovation to the Great Yarmouth Golf Club: “I introduced Mr. Rotherham’s system of playing against an imaginary fixed score for each hole to several members of the Great Yarmouth Golf Club at their Whitsuntide [i.e., mid-May] meeting in 1891” (Golf [London], vol 3 no 78 [11 March 1892], p. 410).

As was required to enable this system of single-day match-play competition, the club secretary, Dr. Thomas Browne (a surgeon in the Royal Navy), worked out the requisite “ground score” for the Great Yarmouth golf course and golfers immediately began informally to compare their score at each hole to the scores making up the theoretical ground score. The reaction of golfers to the difficulty of achieving these scores soon resulted in the name “Bogey” being given to the imaginary person with whom golfers would compete.

Figure 23 Dr. Thomas Browne, Golf Illustrated, 11 July 1902, p. 28.

One of Dr. Browne’s regular playing partners became fascinated with the Great Yarmouth ground score. He was a good golfer but could not match the stipulated score. He enjoyed the challenge but found it frustrating.

One day, he erupted in jocular exasperation at his inability to match the “imaginary” ideal player that Dr. Browne had summoned into existence: “This player of yours is a regular Bogey man!”

He was alluding to a song popular in the early 1890s, “Hush! Hush! Hush! Here comes the Bogeyman!” The lyrics described a mischievous, timorous, hard-to-catch goblin: the Bogeyman.

They ran as follows:

Children, have you ever met the Bogeyman before?

No, of course you haven't for

You're much too good, I'm sure;

Don't you be afraid of him if he should visit you,

He's a great big coward, so I'll tell you what to do:

Hush, hush, hush, here comes the Bogeyman,

Don't let him come too close to you,

He'll catch you if he can.

Just pretend that you're a crocodile

And you will find that Bogeyman will run away a mile.

Browne immediately proposed that the imaginary, mistake-free golfer against whom they were competing be named “Mr. Bogey.” The name became popular, and soon the “ground score” at Great Yarmouth and elsewhere became known instead as the “Bogey” score – an early version of what today we call par for the course.

Then, in the fall, Mr. Bogey joined the armed forces.

An anonymous member of the United Service Golf Club of Gosport, which was organized for the exclusive use of members of the military, wrote to the editor of Golf (London) to explain Mr. Bogey’s commission:

Bogey was introduced to the members of the United Service Golf Club some months ago by the well-known secretary of the Great Yarmouth Golf Club, Dr. T. Browne, R.N. The versatile sportsmen of the United Service Golf Club were not long in trying a taste of his [i.e. Mr. Bogey’s] quality, much to their discomfiture at first, as they did not realise sufficiently that “Bogey” is a player who cannot lose his temper, or be in any way demoralized…. “Bogey” assumed the designation of Colonel on admission to the United Service Golf Club, as naval or military rank is an indispensable qualification for its membership….

Joking apart, the advent of “Colonel Bogey” seems likely to introduce a new and permanent feature into the game of Golf. By using him as an intermediary, one can compete with the whole field simultaneously by match, instead of medal, play….

It appears to me, then, that the so-called “Colonel Bogey” is destined to take and to hold a permanent place in the game of Golf, and to add some fresh and interesting features to the noble art. (vol 3 no 76 [26 February 1892], pp. 384-85)

By 1892, the name “Colonel Bogey” was coming to be used in preference to “Mr. Bogey” by golfers at the several golf clubs in the south of England where Bogey competition had gained a foothold.

Making the Acquaintance of Colonel Bogey

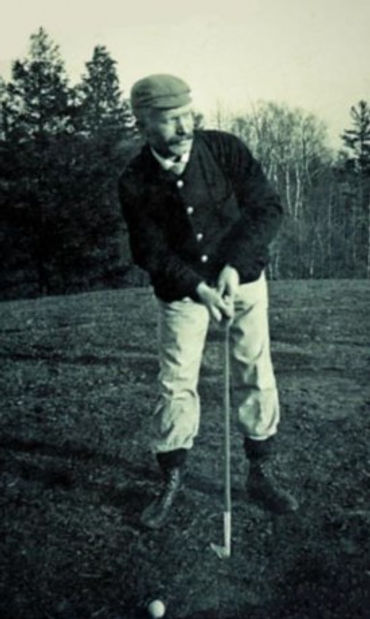

Figure 24 Image of Colonel Bogey, circa 1914.

In the 1890s, it often took a personal introduction to Colonel Bogey for golf clubs to get up the confidence to try out the new-fangled system of Bogey competition.

Such was the situation at the second and third golf clubs to try out this new form of competition: the Great Yarmouth Golf Club and the United Service Golf Club, respectively.

We recall that Coventry Golf Club member Harold Smith had carried news of this new form of match play to the Great Yarmouth Golf Club one week after the first tournament (in which he had finished third).

And Great Yarmouth’s Club Secretary, Dr. Thomas Browne (a surgeon in the Royal Navy), carried news of the fearsome Bogey to fellow military personnel the United Service Club in the fall of 1891, where this fictional figure received a commission at the rank of Colonel.

At every golf club, members needed time to become accustomed to the peculiar features of the competition. Although Rotherham had worked out Coventry’s ground score by February of 1891, it was not until May that he felt club members were ready for a full-scale competition against the ground score. Similarly, although at Great Yarmouth, Browne had learned of the new system of competition in May of 1891 and immediately set about working out a ground score for the Great Yarmouth links (a score that he shared with certain club members who wished to assess their own play by means of it), he reported in Field that the club’s Easter competition in 1892 ten months later “was the first occasion on which such a competition had been attempted on a large scale” (no 2052 [23 April 1892], p. 594).

Although it may be hard for a twenty-first-century golfer to appreciate how difficult it was for golfers in the 1890s to understand and become comfortable with Bogey competition, it is simply a fact that it took time to introduce club members to Colonel Bogey and to establish a rudimentary Bogey culture at a golf club.

Consider all the things that a club secretary, green committee, handicap committee, and regular club members had to work out for the first time.

First, a club secretary or a green committee would have to work out a ground score for the club’s golf course. This had never been done before. And it is unlikely that anyone had ever worked out even a par score for the course. After all, in the early 1890s, it was still the case (much to the frustration of A.H. Doleman) that most members of golf clubs had never heard of the concept of par, let alone knew anything about the practical measurements and calculations necessary for determining it. So, there was a steep learning curve facing those who would for the first time ever work out a ground score for their course.

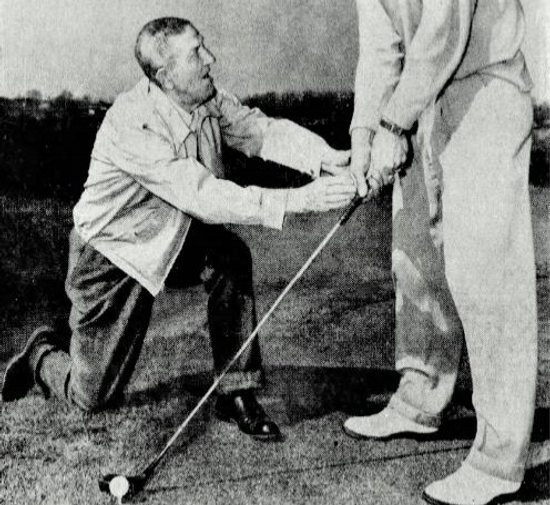

Remember, too, that a par score was not the score to be attributed to Colonel Bogey. The latter was not to be seen as being as good as a golf professional. Instead, he was to be regarded as someone who always played the best game that the club’s top players occasionally played. So even if someone had worked out a par score for one’s golf course, the question remained for those working out a ground score: where would Colonel Bogey take more strokes than a golf professional to reach the green on certain of the holes?

And so, when determining a ground score for their golf course, committee members regularly engaged in argument about how many strokes it should take their best golfers to play this hole or that hole. There was always debate about whether it was appropriate to allow Colonel Bogey to reach a certain green with one shot, or another green with two shots, when it took almost all the club members two shots and three shots, respectively, to do so.

And there was always debate about whether it was appropriate to credit Colonel Bogey with his customary two putts per green. After all, what about the club’s most fearsome putting surfaces where most members took three putts? The only saving grace in the practice of having Colonel Bogey two-putt every green was that he was never allowed to make a two on a three-shot hole, a three on a four-shot hole, or a four on a five-shot hole, although some members would inevitably do so in every Bogey competition.

In Golf Illustrated in 1899, golf writer W.L. Watson gave vent to frustrations arising from his long experience of these sorts of discussions at the West Middlesex Golf Club where he was a member:

The bogey score is not a score at all; it is the product of some imaginary player and the predilections of the club committee.

Figure 25 Colonel Bogey card in the Game of Sporting Snap deck of playing cards, Major Drapkin & Co., 1928.

Figure 26 In the presence of the match referee, two competitors assess a possible stymie occurring in a competition circa 1930.

It is usually arrived at by count of hands.

If a majority decided that any particular hole is too difficult for four, they make it five.

Approaching the matter from the other point of view, they may resolve that it would be too easy in five, and so make it four.

That is bogey: he is really not a bogey at all, but merely a mild-mannered abstraction of votes and opinions, ready to change his play at any committee’s bidding, and hole out in any number of strokes they may suggest….

A most complacent fellow he is, but certainly no bogey, rather a timorous, middle-aged fool.

(Reprinted in Golf [New York], vol 5 no 6 [December 1899], p. 398)

Watson’s West Middlesex committee was used to these sorts of meetings. Golf clubs going through the process for the first time would have found it confusing, disorienting, and frustrating.

And then there was the question of the rules, for in this form of match-play competition, medal-play rules often had to be used in place of the regular match-play rules.

For instance, since the two players sent out together in these competitions were competing not against each other but rather against Colonel Bogey, one player would not be allowed to stymie another.

In regular match play, however, whether occurring by accident or design, a stymie occurred when one golfer’s ball sat on the green between the other golfer’s ball and the hole, such that Golfer A’s ball blocked the hole for Golfer B’s putt.

As indicated in the original rules of golf formulated in 1744, unless the two balls were within six inches of each other, Golfer A’s ball was not lifted, and Golfer B was said to be stymied.

In matches against Colonel Bogey, however, the medal-play convention was observed: a ball on the green interfering with a player’s putt would have to be played first.

Similarly, although in match play one had the option of cancelling an opponent’s shot when it was played out of turn, since players were not competing against each other in a Bogey competition, a stroke played out of turn would not be cancelled: the shot played out of turn was not relevant to a playing partner’s match against Colonel Bogey, and it obviously had no effect on Colonel Bogey’s performance.

And since the Royal and Ancient Golf Club of St. Andrews would not get around to formalizing rules for Bogey competitions until 1911, there were other questions for all clubs to decide.

Would a player who lost a ball lose the hole to Colonel Bogey (as the player would according to the match-play rules of the day), or would the player be allowed a stroke and distance penalty as in medal play – thereby allowing the player the possibility of still competing with Colonel Bogey’s score on the hole?

Playing a wrong ball in match-play resulted in the loss of the hole, but should playing a wrong ball in a Bogey competition result in the loss of the hole, or should the player simply be assessed the two-stroke penalty imposed in medal play and be allowed to continue to compete with Colonel Bogey’s score on the hole?

In the matter of handicaps, however, the match-play convention was followed rather than the medal-play convention. In medal-play, club members received the full value of their handicap, but since high handicappers generally earned their high handicaps not by a consistent performance on every hole but rather by uneven performances on several spectacularly bad holes per round, it was understood that to compete by match play against a good player like Colonel Bogey they did not need their full handicap. They would lose their worst holes to Colonel Bogey by several strokes, but on the holes they played well, their handicap allowance would allow them to be competitive with him.

Still, the handicap committees would have to decide whether players would be allowed three-quarters of their handicap against Colonel Bogey, or just two-thirds. Practices varied in England.

And there were other questions.

How seriously would one take the competitive element of the tournament itself? Most clubs understood that competitors wanted to know the Bogey score they had to beat at each hole, but some clubs seemed to think that “the ‘Bogey’ score should at times be fixed unknown to the competitors” (Golf [London], vol 3 no 75 [19 February 1892], p. 362). For the sake, apparently, of introducing an element of surprise into the calculation of results at the end of the tournament, one accepted that players who “did not know the score they were playing against … might go on hammering when they had possibly already lost the hole” (Golf [London], vol 3 no 75 [19 February 1892], p. 362).

Would the Bogey score be set for the season, or would it be adjusted for each competition, according to prevailing conditions? If the latter, a club would need a diligent committee: “Alter the score according to weather and wind if you like; but, as that would have to be done on the morning of the competition, … it would give more work to the committee than most of them seem to care about” (Golf [London, vol 3 no 75 [19 February 1892], p. 362).

Given the large amount of information that had to be gathered and disseminated, and the large number of questions that needed to be addressed and decided, simply to get well-established English golf clubs ready for their first Bogey competitions between 1891 and 1893, one can appreciate that the staging of the first ever Bogey competition in North America by the Ottawa Golf Club in 1893 would not have been easy.

And given the fact that questions from English golf clubs about how rules should be applied in Bogey competitions were regularly directed to the editor of Golf (London) throughout the 1890s, one can appreciate that golf clubs often relied on someone with experience of Bogey competitions to bring their members up to speed on the nature of this new form of match play and to help them with the organization of their first collective battle with the Colonel.

At the Ottawa Golf Club, that person was its first golf professional, Alfred Ricketts, and he was allowed six months to get everything organized.

Royal Wimbledon's Professional Bogey Man Comes to Ottawa

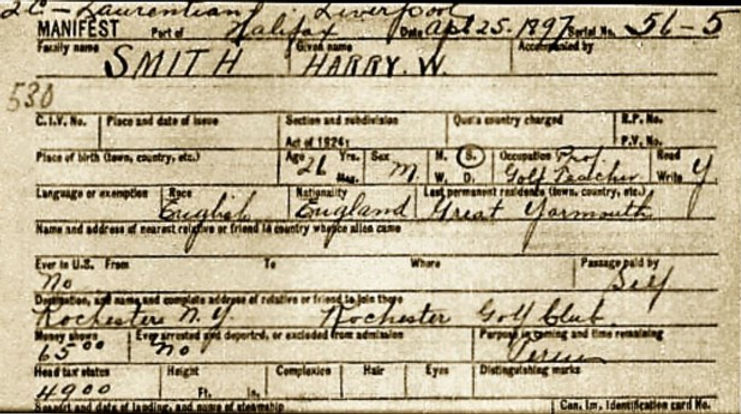

A year before any other golf club in North America became acquainted with him, Colonel Bogey came to Ottawa in March of 1893 when the Ottawa Golf Club hired its first golf professional: Alfred Ricketts, “a professional from Wimbledon” (Ottawa Free Press, cited in the Montreal Star, 2 May 1893, p. 5). The reference to Ricketts as a “professional from Wimbledon” refers not to his birthplace but rather to the golf club where he worked: Royal Wimbledon.

Laid out in the 1860s, the eighteen-hole golf course on the Wimbledon Common was the third oldest in England. It hosted two golf clubs. Located at one end of the course was the London Scottish Golf Club, which operated out of the relatively spartan clubhouse known as the “Iron House” (seen below right); at the other end of the course was the Royal Wimbledon Golf Club, which operated out of the more commodious red-brick clubhouse (seen below left).

Figure 27 Left: Royal Wimbledon clubhouse. Horace Hutchinson, British Golf Links (London: J.S. Virtue, 1897), p. 27. Right: London Scottish clubhouse, circa 1890.

When he arrived in Ottawa, Ricketts was only the second golf professional ever hired in North America. Royal Montreal’s Willie Davis had been the first, but he had left in February for Newport, Rhode Island, and Royal Montreal’s new golf professional, Bennett Lang, would not arrive until mid-May (Golf [London], vol 7 no 170 15 December 1893], p. 218).

So, in March of 1893, Ricketts was the only golf professional in Canada.

Alfred Henry Ricketts had been born in Wimbledon (a town about 10 miles south-west of London, England) in February of 1869, the third of the six children of Letitia and George Ricketts. A carter by trade, George Ricketts seems to have been a successful businessman: he employed several people, including a number of family members, and his home was large enough not only to accommodate his family of eight, but also to accommodate lodgers – even a family of three at one point.

In 1881, twelve-year-old Alfred was working as an errand boy, but by 1891, he had become a golf professional, presumably working as an apprentice to one of the golf professionals at the golf course located on the Wimbledon Common.

Ricketts had sailed to Ottawa in mid-March of 1893, a newspaper reporting the news of his arrival on the first day of spring:

To Boom Golf

Ricketts, the professional, engaged by the Ottawa Golf Club, has arrived here for the season.

Under his tuition, it is expected that Golf will boom. (Ottawa Daily Citizen, 21 March 1893)

Within six weeks of his arrival, Ricketts had persuaded the Ottawa Golf Club’s executive committee to include a “’Bogey’ competition” in its fixtures list.

Ricketts presumably promoted this innovative form of match play in response to the expectation that he would help to “boom” the game. He knew how popular Bogey competitions had become in England, and he had first-hand knowledge of this form of play at Royal Wimbledon.

By the end of April of 1892, Bogey was known only in England, and only to members at Coventry, Great Yarmouth, “the United Services Golf Club, as well as some other southern clubs” (Field, vol no 2052 [23 April 1892], p. 594). Fortunately for the Ottawa Golf Club, Royal Wimbledon was one of the “southern clubs” of England that had among its members a number who were strong advocates of Bogey competition. In fact, one of the members of Royal Wimbledon was promoting Bogey competition at the club by late 1891 and wrote to the editor of Golf in January of 1892, calculating a Bogey score for the Wimbledon course, and recommending Bogey scores be established everywhere as a way for single golfers to play a round of golf without playing out holes on which they were taking far too many strokes:

I am very pleased to see that the “Bogey” play is coming more into fashion, and to see in your interesting paper some competitions played under that system. It savours more of the legitimate match play and makes a little change from the long and tedious medal rounds.

I also strongly recommend it to those players who are so fond of toiling around by themselves, keeping their correct scores, thereby blocking up the greens and proving themselves a nuisance to many. I do not mean that I advocate single play, but that I think that anyone who prefers that way of practice can get along much faster on the “Bogey” plan, and so help less to block up a green. (vol 3 no 71 [22 January 1892], p. 302, emphasis added)

Wimbledon was one of the busiest golf courses in England, with as many as 40 couples on the course at a time, so slow play was always a concern. Since when playing against Colonel Bogey, one would not be playing for the sake of a correct medal score, one would pick up one’s ball after the hole had been lost to the Colonel.

Royal Wimbledon also had a thriving women’s club (the Wimbledon Ladies’ Golf Club) with a course that was also maintained by the Wimbledon professionals: “The course is one of nine holes … and is about 1200 yards in length”; it has “a great many hazards in the shape of whins and gravel bunkers” (The Golfing Annual 1891-92, p. 222; The Golfing Annual, 1893-94, p. 299). And it was on this course that the Wimbledon Ladies’ Golf Club played a well-organized Bogey Competition in mid-November of 1892. It drew over forty entrants (twice the number of playing members at the Ottawa Golf Club at this time).

We can see, then, that during his last two years at Wimbledon, Ricketts would have learned a good deal about the new method of golf competition.

But he would be given a whole season at Ottawa to set up the first Bogey competition to be held in North America.

At the beginning of May, six weeks after Ricketts’ arrival in Ottawa, the club’s Secretary-Treasurer Alexander Simpson informed the Ottawa Free Press that there would be a “‘Bogey’ competition” at Ottawa during the 1893 season. The tournament was scheduled for a Saturday in November, and it is clear that this tournament was Ricketts’ baby, for he offered the winner’s prize himself. The Ottawa Daily Citizen and the Ottawa Journal both published the information about the tournament and its prize that had been supplied by the club secretary, who continued to put the word “Bogey” in quotation marks: “On Saturday next the ‘Bogey’ competition for the handsome prize given by A. Ricketts will take place” (Ottawa Daily Citizen, 1 November 1893, p. 5); “The ‘Bogey’ competition for the Ricketts prize will take place this afternoon at 2:30 sharp” (Ottawa Daily Citizen, 4 November 1893, p. 5).

Just as at Coventry Hugh Rotherham was the only one to step up and offer a prize for the new form of competition he had invented, so at Ottawa Ricketts was the only one to step up and offer a prize for the new form of competition he had introduced. (Note that Ricketts played in many club competitions over his three years at the club from 1893 to 1895, yet this was the only one for which he purchased the prize himself.)

It is also interesting to note that Simpson described the prize offered by Ricketts as “handsome.”

The most important prize offered in 1893 was described as “a valuable cup” given by “Col. Allan Gilmour” for a season-long semi-monthly competition among club members by handicap medal-play (Ottawa Daily Citizen, 5 April 1893, p. 5). And then there were a dozen or so other prizes offered for more ad hoc tournaments, such as the three organized in mid-November: “On Wednesday afternoon next, there will be a competition for a prize offered by the Secretary, on Thursday for one offered by Mr. R.C. Douglas, and on Saturday for one offered by Mr. W.L. Marler” (Ottawa Daily Citizen, 13 November 1893, p. 5). And there were prizes for women’s competitions: “Major St. Aubyn has donated a handsome prize to be competed for by the ladies on Friday, 12th May” (Ottawa Daily Citizen, 24 April 1893, p. 5).

We can see that not every prize was described as “valuable,” and just two prizes were described as “handsome,” so Simpson’s description of Ricketts’ prize as “handsome” signalled that the prize offered by the club’s working-class employee was at least comparable to prizes offered by well-heeled members (and that it was implicitly more splendid than the prizes that received no descriptor at all). By hyping the prize as “handsome,” Simpson perhaps tried to encourage more entries into the strange new tournament.

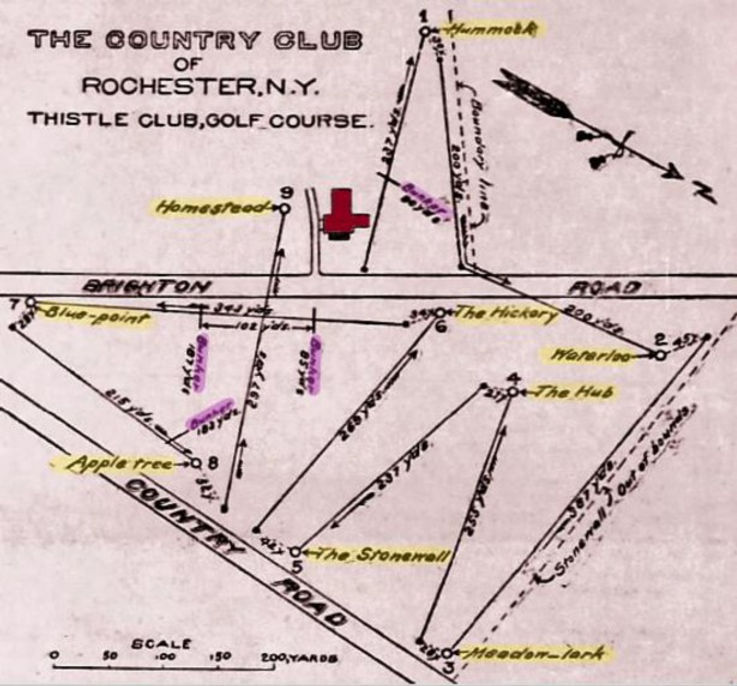

The Bogey Score at Sandy Hill

One of the first things that Ricketts had to do to prepare the Ottawa Golf Club for a “‘Bogey’ competition” was to establish a Bogey score for each hole of its two-year-old golf course.

In 1891, at the end of April, the Montreal golf professional William F. Davis had laid out twelve holes for the Ottawa Golf Club in the part of Ottawa known as Sandy Hill. Nine holes were used as the golf course proper; three holes were used during 1891 as a beginner’s course and practice area. In the spring of 1892, however, these three practice holes were probably re-worked into the ladies’ course laid out before the beginning of the 1892 season.

The golf holes were divided between the meadow at the eastern end of the old By Estate (marked below as B) and the eastern end of the old Besserer Estate (marked below as A).

Figure 28 An enlarged and annotated detail from an 1876 map of Ottawa.

The nine-hole golf course comprised three holes in the meadow west of the Dominion Rifle Range (again, the area marked above as B) and five holes on the higher ground north of the Rifle Range (again, the area outlined above as A). These holes were linked by a hole that went up the steep hill from the meadow to the higher ground.

This nine-hole course ran from a first tee at the clubhouse, which had been built on a high point of land near the junction of Osgoode Avenue and Russell Street, to a green on the flat land across the road from the Protestant Hospital on Rideau Street.

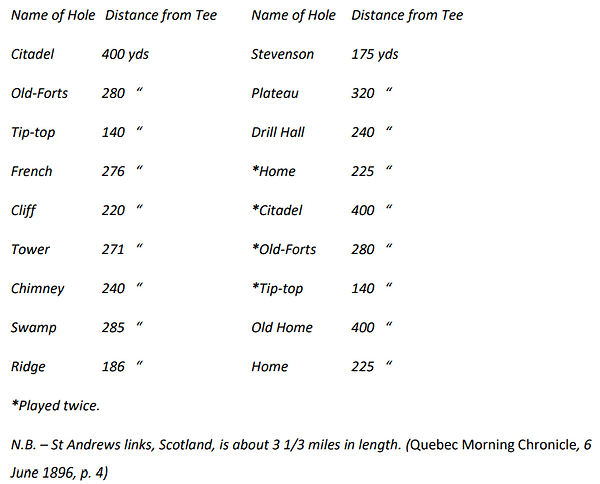

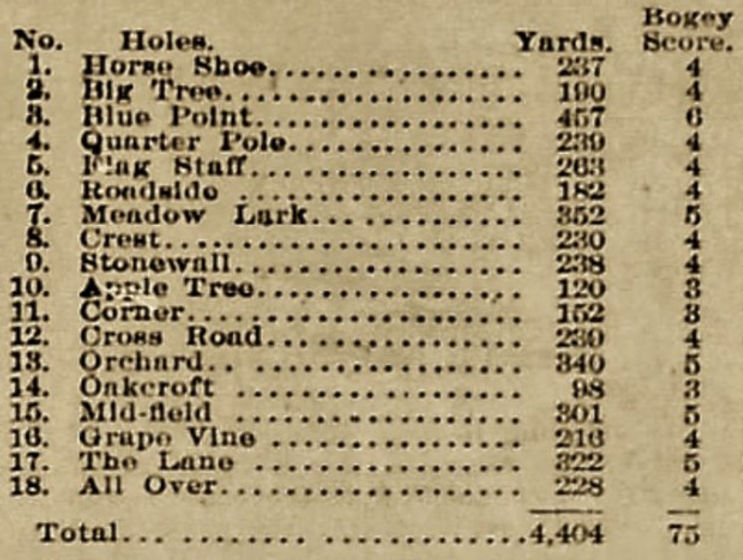

Although there is no record of the official Bogey score accorded to the Ottawa Golf Club’s nine-hole golf course in Sandy Hill, we can make an informed estimate of the approximate score that was attributed to Colonel Bogey that day, for we know both the length of each of the nine holes and the nature of a good number of the hazards associated with them.

And for further context, we can take the Bogey score of the Quebec Golf Club’s fourteen-hole Cove Field course in 1896: with four holes played twice to provide an eighteen-hole score, the length of the course was 4,703 yards: its Bogey score was 87.

Similarly, Royal Montreal’s nine-hole Dixie course (laid out in the fall of 1896 and brought into play in the spring of 1897), when played around twice to produce an eighteen-hole score, had a distance of about 4,900 yards: in the spring of 1898, its Bogey score was reduced to 86. It is not known how much higher than 86 the Bogey score had been when the course was laid out at the end of 1896, but it must have been at least 87.

The Montreal Star published a description of the Ottawa Golf Club’s golf course on 2 May 1893, the year during which the first Ottawa Bogey competition was held: “The links are near the rifle range and form a nine-hole course. The longest run is about 360 yards and the shortest 180, while the whole course is some 2300 yards” (p. 5). The playing length for an eighteen-hole competition would be 4,600 yards.

Similarly, sometime during the 1893 season, club member E.C. Grant wrote for Collier’s Once a Week an article called “Golf in Ottawa”, which appeared in the issue of 30 September 1893. He observed:

The ground is admirably situated for golf, there being plenty of space, and quite enough hazards in the shape of fences, ditches, hills, sand bunkers, etc. There are only nine holes, which are played over twice, but nearly every variety of ground to be found. The longest hole is three hundred and sixty yards and the shortest, one hundred and seventy-five yards, while the whole course is about twenty-four hundred yards. (Collier’s Once a Week, vol 11 no 45 [30 September 1893], p. 5).

And so, we know that the golf course was between 2,300 and 2,400 yards in length. When played around twice to produce an eighteen-hole score, the length of the course would have been, at most, 4,800 yards, which suggests that its Bogey score would have been like those at Quebec and Montreal: around 87 strokes.

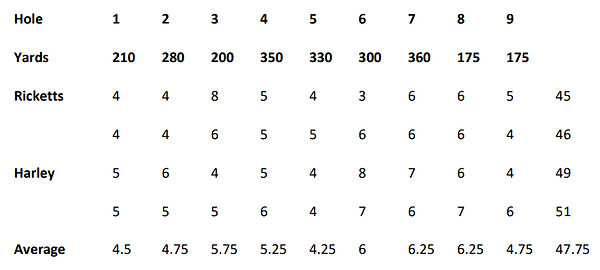

Fortunately, we have information on the kind of scores made on each of the Ottawa golf holes by expert players, for on 24 May 1893, a much-publicized match occurred at Ottawa between the newly-arrived golf professional Alfred Ricketts and Kingston’s newly-arrived crack amateur Thomas Harley (who would win the first amateur Championship of Canada at Ottawa in 1895): Ricketts shot 91; Harley, 100. See below their scores for each of the nine holes that they played four times that day:

The high scores made on certain of the relatively short golf holes on this course by two of the top golfers in Canada in 1893 indicate how penal certain of the hazards proved to be. Ricketts’ score of 91 was probably just a few strokes above what he would have set as the Bogey score for the course.

In the mid-1890s, Ottawa Golf Club secretary Alexander Simpson (who was also the club’s “scratch” player) twice wrote to the editor of Britain’s Golfing Annual to describe these hazards. In his letter for the 1893-94 volume, he writes: “The green has at present only nine holes, and is intersected by sand bunkers, roads, fences, and patches of rough ground” (p. 351). In his letter for the 1894-95 volume, however, he revises this description slightly to warn visitors that the course is harder than he originally suggested: “The course of nine holes is an exceedingly difficult one, being intersected in all directions by heavy bunkers, hills, roads, and rough ground” (p. 400, emphasis added to show new elements).

Both the Collier’s and the Montreal Star articles describe the golf course and the disposition of its hazards more or less hole-by-hole. Furthermore, Grant also commissioned for his Collier’s article detailed sketches of the first, fourth, seventh, and ninth holes.

Hole #1

According to the Montreal Star, “For the first, one has to tee immediately in front of the club house. A low swampy rocky piece of ground has to be covered, extending about 150 yards, and woe to the luckless wight who gets into it. If this is successfully carried, the player finds himself within about 30 yards of the hole. And with good ground before him” (2 May 1893, p. 5). An article in the same newspaper later in the year similarly observes that “A start is made from a high hill and before reaching the first hole a very bad swamp has to be navigated” (7 October 1893, p. 9). Grant describes the hole in similar terms: “The first teeing ground is near the clubhouse, and the course to the first hole is from the top of a very steep hill over a tract of about one hundred and fifty yards of swampy ground, which, if cleared, leaves the player about sixty yards of nice green (i.e., fairway] to finish the hole in” p. 5). The various accounts disagree only as to whether the hole was 180 or 210 yards long.