CONTENTS

The Rise of Golf in New England

The Unknown Original Nine-Hole Course

The Addition of Three New Holes

Willie Campbell’s Extended and Lengthened Course

Fall 1893 and Winter 1894 Golf Ambitions at The Country Club

The New Golf Committee Chairman

It's November 1893: Who Ya Gonna Call?

Talking “New Courses” and “New Links” in March, April, and May 1894

Introduction

In an essay dating from early 1896, Willie Davis mentions the golf courses he has laid out since arriving at Newport in March of 1893. The first club on the list is surprising: "Since I came to Newport, I have laid out links for the Country Club, Brookline, Mass...." (William Frederick Davis, autobiographical statement, undated, courtesy of Royal Liverpool Golf Club).

Figure 1 William Frederick Davis (1862-1902), circa 1892. Golfer, vol 2 no 2 (December 1895), p. 51.

Davis continues his list of organizations and people whose nine-hole links he had laid out between March of 1893 and January of 1896, including (in order): “Country Club, Providence, R.I” (Davis laid out this nine-hole course late in the fall of 1893 or early in the winter of 1894); “Dr. W. Seward Webb, Shelbourne Farms, Vt” (this nine-hole course was laid out by Davis early in 1894, with improvements by him in 1895); “Ogden Mills and W.B. Dinsmore, Staatsburgh, N.Y.” (begun in 1893, this ten-hole course was opened for play in 1894; a New York Evening Post article in 1896 says that the course was laid out by Dinsmore assisted by Davis); “Hot Springs, Virginia” (the nine-hole course seems to have been laid out by the summer of 1894, when a newspaper referred to the imminent formation of a golf club in connection with the Hot Springs Hotel); “George W. Vanderbilt, Biltmore, N.C.” (this nine-hole course was laid out late in December of 1895 and early in January of 1896).

Although we have only Davis’s word that he laid out a course for The Country Club, his list of the various links he laid out is otherwise accurate.

Note also that his list of the work he did seems to have been chronological, implying that he laid out his course at The Country Club first: that is, as early as the fall of 1893.

If Davis indeed laid out links at The Country Club late in 1893 or early in 1894, this would mean that before the United States Golf Association was founded in December of 1894 by the St Andrews Golf Club of Yonkers, the Chicago Golf Club, the Shinnecock Hills Golf Club, the Newport Golf Club, and The Country Club at Brookline, Davis had laid out golf courses for three of them: the original 9-hole course at the Shinnecock Hills Golf Club in 1891 (as well as a ladies’ course about a mile long), the 1893 and 1894 nine-hole courses of the Newport Golf Club (as well as a six-hole beginner’s course), and a previously unknown course at The Country Club at Brookline.

Figure 2 "W.F. Davis, The Crack Golf Player." New York Herald, 30 August 1891.

As the first golf professional to provide a proper test of golf for the members at Shinnecock, Newport, and The Country Club, Davis would be indisputably the most important early course designer in the United States, helping to create an energetic and effective enthusiasm for golf among the members of three of the five the clubs that would found the USGA.

Yet existing accounts of the origins of golf at The Country Club make no mention of a Willie Davis design.

Nonetheless, could his claim be true?

It turns out that there are gaps in the story of the creation of the first nine-hole course at The Country Club: it is possible that in the late fall of 1893 and early winter of 1894, Davis was tasked both with improving the existing golf course laid out by three club members in the spring of 1893 and with adding three new holes on the property.

A Character Reference

After twenty years of service in the North American golf industry (in Canada from 1881 to 1893 and in the United States from 1893 to 1902), Willie Davis “stood high in the good opinions of the amateurs and professionals throughout the country” when he died unexpectedly at forty years of age in 1902 (New York Sun, 10 January 1902, p. 4).

It was said that “Davis had a brusque but pleasant manner,” and it is clear he was not afraid to tell the truth, even when it might have been against his own financial interest, as when he demurred at the idea of laying out a golf course where the people proposing to start a golf club at Shinnecock Hills wanted to build one. Disappointed by the land he was shown, Davis informed founding member Samuel L. Parrish: “Well, sir, I don’t think you can make golf links out of this sort of thing” (New York Sun, 10 January 1902, p. 4; New York Times, 8 March 1896, p. 25). As Parrish later recalled, Davis was ready to return to Montreal: he “turned to me and remarked in a somewhat crestfallen manner that he was sorry that we had been put to so much trouble and expense” (Samuel L. Parrish, Some facts, reflections, and personal reminiscences connected with the introduction of the Game of Golf into the United States, more especially as associated with the formation of the Shinnecock Hills Golf Club [privately printed by Samuel Parrish, 1923], p. 6).

Of course, after Davis explained what kind of terrain was needed, Parrish immediately showed him a different parcel of land nearby, and the work of building the first golf holes at Shinnecock Hills began shortly thereafter.

That Davis’s list of the golf courses he had laid out between his arrival at Newport in the spring of 1893 and his writing of his autobiographical essay in the winter of 1896 seems to be accurate should be no surprise. He was a stickler for fact when it came to discussing early developments in American golf.

For instance, when a supporter of Willie Dunn, Jr, wrote to the editor of Golf (London) at the conclusion of Dunn’s 1893 “visit of five months in the United States” as the resident professional at Shinnecock Hills, Davis was shocked to read:

When Dunn arrived in America, he found three clubs in existence, and when he left there were over forty clubs …

Newport is the Golf headquarters of America, and there Dunn was warmly welcomed.

He laid out a fine new course for the Newport Golf Club and inaugurated its completion by playing for the Championship of America against William Davis, the Champion of Canada….

To show the interest taken in the event, I may state that Dunn, instead of having a “laddie” to carry his clubs, was honored by the attendance of two well-known millionaires, who stuck to him through a heavy thunder and rain storm ….

(Golf, vol 7 no 165 [10 November 1893, p. 134).

Dunn’s New York acquaintance who wrote the letter had not witnessed the match, and, since just five spectators from Newport and two caddies were present at the match, the writer presumably based his letter on what Dunn had told him about the event.

Figure 3 Willie Davis (bottom) and Willie Dunn, Lenox Links, Massachusetts, 28 September 1895. Photo courtesy of Susan Martensen (great-granddaughter of Willie Davis).

The letter puffed up newcomer Dunn not just at the expense of Davis, but also at expense of the truth, and so, Davis wrote to the editor of Golf requesting an opportunity to reply to the letter:

As the statements made therein are very misleading and unjust to myself, I feel in duty bound to explain the situation through your valuable paper….

[At Newport in the spring of 1893,] I laid out a course of nine holes, and the club opened on June 15th….

There was never any game played for the Championship of Canada; consequently, I have no claim to that title….

[When he came to Newport to play an exhibition match,] Dunn declined to play the first day, which was fine [weather]; the second day was a rough, stormy day, so we played the game, with four gentlemen and one lady for spectators….

The caddies refused to go more than one round, and two members kindly carried our clubs for the remainder of the match.

As for the statement that Dunn found three clubs in existence and left forty, it is a false statement. (Golf, vol 7 no 170 [15 December 1893], p. 218)

Davis reveals here the origins of his impatience with the self-promoting behaviour of Dunn.

Of course, Davis was not just correcting the historical record; he was also standing up for himself. But he was also willing to stand up for others against Dunn.

Figure 4 Horace Rawlins, circa 1895.

Two years later, for instance, he stood up for his former assistant, Horace Rawlins, when, once again, he found Dunn spreading inaccurate information via an interview with a New York newspaper. The item that upset Davis read as follows:

Willie Dunn, the golfing champion, … arrived early yesterday morning [in New York] …. Dunn has sold out his business at Biarritz, and this country will hereafter be his home….

[Dunn’s nephew Samuel] Tucker met Horace Rawlins in England, who won the professional championship at Newport last October …. Rawlins has been playing steadily on the other side and has a match on with J. Braid of Eley, the English professional.

Braid played against J.H. Taylor on Dec. 14 and was beaten somewhat easily.

The game [between Braid and Rawlins] should give a line on the comparative merits of the English and American players.

(Sun [New York], 8 March 1896, p. 8)

Davis went to The Evening Telegraph of Providence, Rhode Island, to complain that Dunn’s gossip was not just inaccurate, but a slight both upon Rawlins in particular and upon the golf professionals working in America in general:

WHO IS THE CHAMPION GOLFER?

Supt. Davis of Newport Club Takes Exception to Statements

Newport, March 14. — W.F. Davis of Newport Golf Club takes exception to a recent article in a New York paper which stated and referred to Willie Dunn as the champion golfer.

Mr. Davis stated to the Telegraph correspondent that there was but one championship game played in this country and that was won by Mr. H. Rawlins, which occurred on the Newport links last fall.

The article went on to state that J. Braid of England, who played a match with Mr. Rawlins …, was beaten badly in his match with Taylor, the Open champion ….

Mr. Davis states that such a statement is incorrect.

Taylor and Braid tied in their match of thirty-six holes and Braid made a record of the links, seventy-one, in this match.

Continuing, Mr. Davis stated that the article went on to state that a line would be drawn between the American and English players, and Mr. Davis believes it would be well for the American lovers of this game to know exactly the facts as they exist in this case ….

(The Evening Telegraph [Providence, R.I.], 14 March 1896, p. 3)

Rawlins had lost his match against Braid, but he had played very well, and so Davis was outraged that Dunn implicitly diminished the twenty-year-old Rawlins’ accomplishment by falsely stating that Braid had been beaten by Open champion Taylor (and “beaten somewhat easily”), when the truth was that American champion Rawlins had put up a very good fight against the man who had tied the British champion and set a course record in doing so.

Figure 5 A sketch of Willie Davis, The Evening Telegraph (Providence, R.I.), 31 March 1896, p. 6.

The Evening Telegraph of Providence seems to have been Davis’s favorite newspaper. In the spring of 1896, several passages of the autobiographical essay in which Davis says that he laid out a course for The Country Club were quoted verbatim in an article about him published in The Evening Telegraph: “A Prominent Golfer: Brief Sketch of W.F. Davis of the Newport Club” (31 March 1896, p. 6). He seems to have provided his autobiographical essay to the newspaper so that it could write up this article about him.

The Evening Telegraph left out about half of the courses that Davis had listed as laid out since 1893. Presumably the editor thought them of little interest to Providence readers.

Still, it seems that that Davis had provided to the newspaper his list of courses laid out and was fully prepared to receive public scrutiny for his statement: "Since I came to Newport, I have laid out links for the Country Club, Brookline, Mass...."

In other words, he feared no contradiction of this claim.

Davis’s reputation for honesty and integrity endured. It should be no surprise to find the New York Times congratulating the Apawamis Golf Club on acquiring Davis from Newport in 1899, implicitly contrasting him with none other than the notoriously self-promoting Dunn (known for avoiding exhibition matches he feared he would lose):

The Apawamis Club may be congratulated on securing so able a professional, for among the host of Scotchmen who have come to America to help promote knowledge of the game, Davis can be numbered in the top ranks.

With a thorough knowledge of all technicalities of the links, as well as possessing grand talent of reliability, Davis will always add a certain golfing tone to whatever club he may be connected with.

As a player, his ability has always been recognized, but he has not descended to that advertising method of backing himself for matches to redound to his own honor.

(New York Times, 12 November 1899, p. 10)

Similarly, the New York Sun observed that Davis acted “in accordance with his principles” and was “always an upholder of probity in professional golf” (New York Sun, 10 January 1902, p. 4).

As I see it, Davis’s demonstrated concern for historical accuracy, the golfing community’s pronounced respect for his personal integrity, and Davis’s willingness to publish his statement that he had “laid out links for the Country Club, Brookline,” require that we take this statement seriously.

The Rise of Golf in New England

As the popularity of golf spread from Scotland throughout England in the late 1880s and early 1890s, wealthy American families who spent time in the United Kingdom, or who vacationed at French resorts where British visitors had established golf clubs, such as at Pau and Biarritz, began to bring back to the American Northeast news of this old Scottish game.

In Massachusetts, by 1890, rudimentary golf courses had been laid out on a private estate and in a public park.

Figure 6 Lawrence Estate, Groton, Massachusetts, 1888.

The Boston Globe reported in May of 1894 that the golf courses in and around the city of Boston at that time had in a sense descended "from a few improvised links at Mr. James Lawrence's country place at Groton, where the game in this part of the country started some four years ago" – that is, 1890 (20 May 1894, p. 30).

James Lawrence was a founding member of the Country Club in 1882 and his estate was about forty miles northwest of Boston.

But his younger brother Prescott was the real golf enthusiast in the family.

Prescott Lawrence had been a regular resident of the Newport cottage colony since the mid1880s and became a founding member of the Newport Golf Club in January of 1893. He may have been one of the people who played golf on the nine-hole course that Theodore Havemeyer laid out at Brenton Point in Newport in 1890. Late in the summer of 1893, he bought his own home in Newport, at which he entertained his brother James during September, when Prescott entered a golf tournament held at the Newport Golf Club over the Labor Day weekend.

If James and Prescott Lawrence had indeed started playing golf on “improvised links” (the one at Groton and the other at Newport), they will have been very impressed by Davis’s Newport course in 1893. It may have been at this time that James Lawrence engaged Davis to work for him, for Davis writes his 1896 autobiographical essay, “Since I came to Newport, I have laid out links for the Country Club, Brookline, Mass.; Country Club, Providence, R.I.; Mr. Jas. Lawrence, Groton, Mass….” (Davis, autobiographical statement, undated, courtesy of Royal Liverpool Golf Club). Davis’s work at Groton was probably in late in 1893 or early in 1894.

Also in 1890, George Wright famously attempted to popularize the ancient Scottish game in Boston itself.

That fall, his sporting goods company, Wright & Ditson, had acquired a supply of golf clubs from Scotland. Ever the entrepreneur, Wright organized a proper – and well-publicized – game of golf in Franklin Park in December of 1890:

Figure 7 George Wright (1847-1937), circa 1900.

Initial Game of Royal Golf

The Great Scotch Sport Played for the First Time in this Vicinity on Franklin Park Yesterday….

The gentlemen composing the “foursome” were Messrs. Fred Mansfield, the expert tennis player and cricketer, Sam [Mac]Donald, George Wright, and Temple Craig, while Mr. J.B. Smith filled the onerous position of scorer….

Everybody interested contributed something: the park commissioners the ground, Wright & Ditson the clubs and balls, Mr. Smith dug the holes and scored, and the other players gave their time and energy.

(Boston Globe, 13 December 1890, p. 6)

Poor Smith, the official scorer, had to use an axe to chop holes in the frozen ground for the cups and flagpoles.

Wright organized a second match on a twelve-hole and eleven-hole course on Crescent Beach at the end of March in 1891, and he seems to have been out again in December of 1891 (Boston Globe, 29 March 1891, p. 6; 4 December 1891, p. 12).

But the seminal moment in the establishment of the new game amongst the Boston “swells” (as the socially and financially elite set was known) has always been ascribed to the introduction of golf on the estate of Arthur Hunnewell late in the summer of 1892:

Golf was first played in New England at Wellesley, Mass., on the estate of Mr. Arthur Hunnewell.

A young lady from Pau [Arthur Hunnewell’s niece, Florence Boit], visiting his family in the summer of 1892, brought with her a set of clubs, balls, etc., and showed the manner of using them.

Figure 8 Arthur Hunnewell (1845-1904). Wellesley, Hunnewell Family archives.

Mr. Hunnewell, Mr. R.G. Shaw, and his nephew, Mr. Hollis Hunnewell, owning adjacent estates, all ardent lovers of out-ofdoor sports, were quick to recognize the attractions of the new game, and they and a few of their friends eagerly adopted it ….

Thus during October and November several of Mr. Hunnewell’s friends were invited out to try it, and on his grounds about a dozen men made their first acquaintance with the game.

His course was not a bad one.

It ran over undulating lawn and park, and consisted of seven holes of fair distances; the holes were sunken five-inch flower pots; the hazards consisted of avenues, clumps of trees, bushes, beds of rhododendrons and azaleas, an aviary, green-houses, and an occasional drawing-room window-pane; and many were the narrow escapes of the ladies and children on the piazzas at the hands of the enthusiastic players, who were totally ignorant of the force and “carry” and range of a fairly hit golf ball.

Figure 9 Circa 1901, Arthur Hunnewell (wearing a white shirt, with a golf bag on his shoulder) stands near the hole-marker on the 2nd hole of his golf course. He plays golf with three relatives. Wellesley, Hunnewell Family Archives.

After seeing and playing the game, and witnessing the enthusiasm of all who had been fortunate enough to participate in it, the present historian wrote a letter to the Executive Committee of The Country Club, setting forth that there was a new game called golf (it had been played in Scotland for over three hundred years!); that it appeared as if it might readily be introduced at the Country Club; that the cost of an experimental course need not exceed fifty dollars; that the following members of the club (giving a list of eight or a dozen names) were more or less familiar with the game (from having played it two or three times!), and that they therefore joined in requesting the committee to allow it a trial.

(Laurence Curtis, “The Rise of Golf in New England,” Golfing, vol 1 no 5 [September 1895], pp. 125-26)

At The Country Club, the minutes of the Executive Committee meeting of 29 November 1892 record the Committee’s decision: “A letter from Mr. Laurence Curtis requesting that a Golf course be constructed was read. Voted: That Messrs. Arthur Hunnewell, Laurence Curtis and Robert Bacon be appointed a Committee on Golf and lay out a course and spend [the] necessary amount up to $50” (cited by Massachusetts Historical Society, https://www.masshist.org/object-of-the-month/objects/june-2022).

Covering First Course Facts

The passage cited above about the beginnings of golf at The Country Club is from Laurence Curtis’s essay, “The Rise of Golf in New England,” which appeared in Golfing, the first American golf magazine (vol 1 no 5 [September 1895], pp. 125-29).

Figure 10 Golfing, vol 1 no 5 (September 1895).

Curtis wrote the essay less than three years after he wrote to the Executive Committee of The Country Club requesting permission to lay out “an experimental course.”

In 1932, his essay became the basis of the official narrative of the birth of golf at The Country Club at Brookline, a narrative presented in The Country Club: 1882 – 1932, by Frederic H. Curtiss and John Heard (Brookline, Mass.: privately printed, 1932).

Figure 11 Laurence Curtis (1849-1931), St Andrews Golf Club at Yonkers, October 1894.

Curtiss and Heard express complete confidence in Laurence Curtis’s 1895 account of the rise of golf in New England generally and of the rise of golf at The Country Club particularly: “As at that time, Mr. Curtis was vice-president of the United States Golf Association, and was also secretary of the Golf Committee at the Country Club, his remarks may be regarded as authoritative, and therefore are here quoted in full” (p. 64). And so, both the passage I have quoted above and also several more paragraphs of Curtis’s essay are reproduced by Curtiss and Heard.

And yet, as we shall see, on one occasion, Curtiss and Heard completely disregard certain of Laurence’s remarks that contradict the narrative that they prefer.

On another occasion, to corroborate their narrative, they even change Laurence’s remarks without any acknowledgement that they have done so.

It turns out, then, that for reasons they never explain, Curtiss and Heard decide that important parts of Laurence Curtis’s narrative are not “authoritative” at all.

1892 or 1893?

In his 1895 essay, Laurence Curtis accurately notes that The Country Club’s Executive Committee “on November 29 [1892] appointed Messrs. A. Hunnewell, Laurence Curtis and Robert Bacon a committee to lay out a course”; but he immediately adds: “it was too late in the year to do anything then [November 1892],” and so “they laid out in March, 1893, a course” (pp. 125-26).

Evidently, there was no golf course laid out in the fall of 1892.

Figure 12 The Country Club: 1882 - 1932, p. 69.

Yet Curtiss and Heard write: “Golf at The Country Club dates from 1892, when the preliminary six-hole course was laid out, all of it on the front land, and not until 1893 did these premises prove inadequate” (p. 31).

They imply that golf was played in 1892 on a six-hole course and that members were initially quite satisfied with it.

They even publish a map of this six-hole course (seen to the left) and they date it 1892.

The only contemporary support for their claim that I have found comes from an oddly contradictory statement in the Boston Globe in 1899:

“In the autumn of 1892, the first golf was played at the Country Club, Mr. Lawrence [sic] Curtis, Mr. Arthur Hunnewell and Mr. Robert Bacon being then appointed a committee to lay out a course of nine holes, which was done in March, 1893” (Boston Globe, 2 April 1899, p. 36).

This newspaper report seems to confuse the 1892 appointment of a Golf Committee with the playing of the game at that time. Then it contradicts itself by indicating that a golf course was not laid out until “March, 1893” – as Laurence Curtis had said it was.

Of course, readers will have noticed that the newspaper says that it was “a course of nine holes” – not six holes – that was laid out in March of 1893.

So, what’s the story? Did the first layout have six holes or nine holes?

Six Holes 1892

Whence arises the idea that the original golf course at The Country Club had just six holes?

The first reference to this idea that I can find in local newspapers comes from an account of a talk given in the spring of 1914 to about 100 members of The Country Club by the Chairman of the Golf Committee at that time, George Herbert Windeler (1861-1937).

By that point, Windeler had been chairman of the Golf Committee since the spring of 1899, and he had been a member of the Golf Committee well before that point, probably serving as committee secretary as early as 1896, for he was said to have been the one who hired in the spring of that year the young golf professional who succeeded Willie Campbell at The Country Club: twenty-five-year-old George Douglas from North Berwick, Scotland (1871-1903) (https://www.douglashistory.co.uk/history/george_douglas12.html).

Figure 13 George Herbert Windeler (1861-1937), USGA President, 1903-04.

Born in London in 1861 but residing by the early 1890s in Long Ditton, Surrey, England, Windeler had arrived in Boston in the spring of 1894 in advance of his impending marriage to a socially prominent young Boston woman, Laura Wheelwright. He first played the golf course in May of 1894 as a guest and that month established the nine-hole amateur scoring record (46).

After their marriage in June, he and his wife spent most of the year in England, but they returned to Boston in mid-November and Windeler shortly thereafter became a member of The Country Club. He developed business interests in shipping and insurance and maintained homes in Boston and England. He would found the Massachusetts Golf Association in 1903 and he would serve as president of the USGA from 1903 to 1904.

A reporter for the Boston Evening Transcript summarized Windeler’s 1914 presentation:

What the policies of the golf committee of The Country Club have been in the past were explained and what they should be in the future were discussed at a meeting in the clubhouse at Brookline last evening.

There were upwards of a hundred members present … in a room upstairs where there was a pictorial review, by radiograph slides, of the steps in the progress of The Country Club links from the time of their establishment in 1892 up to the present. G. Herbert Windeler, chairman of the golf committee, traced the history of golf at the club, explained the pictures and the charts of the different courses, and proved himself quite as capable a lecturer as he has been a golf chairman….

There were men present at last evening’s meeting who have been identified with The Country Club for more years than golf has been played there, but it is doubtful if there were more than half a dozen in the room who had a real conception of the task involved in bringing the course up to the present standard [of eighteen holes], as explained to them by Mr. Windeler….

No place could have been less naturally adapted for the development of a good golf course than the property which The Country Club owns.

The beginning of golf came in 1892, when, on Nov. 29, it was voted, on motion of Mr. Davis, that Arthur Hunnewell, Laurence Curtis and Robert Bacon be appointed a committee on golf and that they be authorized to spend the necessary amount, up to $50, for the layout of a course.

Then was displayed on the screen the old six-hole course, with its first tee where the caddy house is located now.

(Boston Evening Transcript, 4 April 1914, p. 8)

Figure 14 Boston Evening Transcript, 4 April 1914, p. 8.

The newspaper article gives the impression that Windeler showed his slide of a six-hole course to illustrate the original layout, yet it is not explicitly stated that Windeler said that the original golf course was a six-hole layout: it is merely reported that, after noting the appointment of the original Golf Committee and the approval of its mandate to lay out a golf course, Windeler projected a map of “the old six-hole course” onto the screen (seen above, the map shown by his radiograph slide is the same as that of Curtiss and Herad, except that the latter have numbered the holes on their version of the map).

We must bear in mind, however, that the Boston Evening Transcript reporter provides not a verbatim record of Windeler’s talk, but a summary and paraphrase of it. Only occasionally does he quote Windeler’s actual words.

I note that the reporter was allowed to reproduce two of Windeler’s radiograph slides, which makes me wonder whether Windeler might also have allowed him to use a copy of his lecture notes as the basis for the subsequent newspaper article about the lecture.

Windeler will never have played the six-hole course that he showed on the screen, for he arrived in Boston in May of 1894 when the course in play since the beginning of that month was what newspapers called “the new links” – the nine-hole course over which Willie Campbell and Willie Davis played their celebrated exhibition match on 18 May 1894. (Some days before the match between the professionals, Windeler had established the amateur record of 46 strokes for this course.)

What is the source of Windeler’s map of a six-hole course in front of the clubhouse?

When he prepared his talk in the spring of 1914 about the twenty-two-year history of The Country Club’s golf course, had Windeler seen Executive Committee minutes from the fall of 1892 showing a map or diagram of the sort he produced on his 1914 radiograph slide?

Or, had he perhaps seen Executive Committee minutes from the fall of 1892 which verbally described the course planned by Curtis, Hunnewell, and Bacon – and did so in such detail that he was able to draw up a map of six holes on the basis of that text?

After all, although Laurence Curtis says that it “was too late in the year to do anything” after the Executive Committee’s official approval of the experimental course in November of 1892, he also writes ambiguously about the events that followed. He says that he, Hunnewell, and Bacon “studied the ground” and “laid out in March, 1893, a course” (p. 126). Considering the ambiguous syntax of his sentence, one cannot tell whether Curtis means that the men studied the ground in the fall of 1892 or whether he means that they studied the ground in the spring of 1893.

That is, it is possible that they “studied the ground” in the fall of 1892 and perhaps committed to paper at that time a map or hole-by-hole description of a six-hole course they planned to lay out the next spring.

Could Windeler have misinterpreted a record of the original designers’ intentions in the fall of 1892 as evidence that such was the first course laid out at The Country Club in the spring of 1893?

One must also ask why Curtiss and Heard date their map of a six-hole course “1892”?

Did they merely reproduced Windeler’s map and add the date 1892 to it because they misinterpreted the reporter’s ambiguous reference in 1914 to “the steps in the progress of The Country Club links from the time of their establishment in 1892” as indicating that a golf course had been laid out in 1892 (Boston Evening Transcript, 4 April 1914, p. 8, emphasis added).

We can tell that the newspaper account of Windeler’s talk was an important resource for Curtiss and Heard, for the latter lift a sentence from the former to use in their book. Curtiss and Heard write: “our first course was a six-hole affair, but in 1893 the club became more liberal, and, instead of continuing its original appropriation of $50, the Committee spread itself to the extent of $100 ‘for improving the course,’ and also authorized the addition of three new holes” (p. 68). Curtiss and Heard’s phrase “in 1893 the club became more liberal” comes from the article about Windeler’s talk: “1893, the club became more liberal toward golf” (Boston Evening Transcript, 4 April 1894, p. 8). Evidently, Curtiss and Heard had carefully studied the 1914 article about Windeler’s lecture on the history of golf at The Country Club.

Another possibility is that in 1914, as Windeler researched the history of The Country Club’s golf course, he was told by one or two of the club’s old-timers that the original course had just six holes.

If it is true, as Curtis asserts, that he, Hunnewell, and Bacon had laid out nine holes in March of 1893, one wonders whether three of these holes were removed from play during the course of the 1893 season, creating the impression among those who took up the game later in 1893 that the original course had just six holes. We know, for instance, that play on the home hole endangered people on the piazza. Was this hole removed from play until a new location for it could be found?

Note also that Curtis and Heard mention conflicts from the beginning between golf and polo, between golf and shooting, and between golf and racing. Similarly, the Massachusetts Historical Society quotes a golfer’s recollections of such early tensions:

[Golfers] were jumped upon by the Racing Committee for interfering with their course; they were jumped upon by the pigeon shooters.

The Grounds Committee … thought us vandals if we wanted anything in the nature of trees cut down ….

The wives of some of the members [complained] that we were corrupting the morals of the people of Brookline … by permitting the playing of golf on Sundays.

(https://www.masshist.org/object-of-the-month/objects/june-2022)

If they were found to have interfered with other activities, could two or three holes of the original Curtis, Hunnewell and Bacon nine-hole layout have been taken out of play at some point during the 1893 season to mollify club members outraged by the golfers’ imperial ways?

Nine Holes 1893

A contemporary newspaper article supports Laurence Curtis’s 1895 claim that nine holes were laid out in the spring of 1893, for it explicitly refers in mid-May to a nine-hole course at The Country Club: “About Boston, there are only three links, one at Franklin Park, one at the Hunnewell place at Wellesley, and a half link – nine holes – at the Country Club” (Boston Evening Transcript, 15 May 1893, p. 7).

It is clear from what he says that this newspaper’s reporter had just visited The Country Club and watched people playing on the golf course:

Upon almost any of these fine spring afternoons, two men may be perceived walking hastily across the lawn of the Country Club at Clyde Park, Brookline.

One of these men carries a bundle of sticks in form not unlike the hockey sticks of boyhood, while the other, with a stick similar to the one carried by his companion, knocks a small white composition ball into little holes in the earth, the holes being indicated by small red flags.

(Boston Evening Transcript, 15 May 1893, p. 7)

So, a reporter who was actually on the grounds of The Country Club in May of 1893, and saw the small red flags flying at the golf holes, says that the course comprised nine holes.

Whatever their authority for claiming that the original layout at The Country Club comprised just six holes, Windeler (in 1914) and Curtiss and Heard (in 1932) simply do not address the claim made by Laurence Curtiss (in 1895) that he, Hunnewell and Bacon had laid out a nine-hole course in March of 1893.

During his talk, Windeler prompted “vigorous applause” from club members when he said, “we ought to take off our hats for what [Laurence Curtis] has done for golf at The Country Club,” but he remained silent about the Laurence Curtis essay from twenty years before (Boston Evening Transcript, 4 April 1914, p. 8).

As we know, Curtiss and Heard not only read that essay but quoted it and celebrated it as authoritative. Yet when they quote certain passages, they change what Curtis said, although they pretend that the following sentences are verbatim quotations of his essay:

the committee, no member of which had ever seen a golf links, studied the ground, and as soon as the winter snows and frosts had disappeared, they laid out in March, 1893, a course of six holes ….

The time had come to show the game to the members….

The whole crowd evinced an active interest which increased as the game went on, and they followed through the six-hole course, extending to more than a mile, and the game was made. (The Country Club: 1882 – 1932, p. 66, emphasis added).

Curtis wrote something very different:

The committee, no member of which had ever seen a golf-links, studied the ground, and as soon as the winter snows and frosts had disappeared, they laid out in March, 1893, a course of nine holes ….

The time had come to show the game to the members ….

The whole crowd evinced an active interest, which increased as the game went on, and they followed through the nine-hole course, extending to more than a mile, and the game was made.

(Laurence Curtis, “The Rise of Golf in New England,” Golfing, vol 1 no 5 [September 1895), p. 126, emphasis added).

The sentences that Curtiss and Heard print in their book are obviously not the result of typographical errors; they are the result of historical revision aforethought. They do not even acknowledge that they have rewritten Curtis’s text, let alone explain why they have done so – a very odd thing for historians to have done!

Mathematics

Could bad math have motivated Windeler to ignore Laurence Curtis’s claim that the original course laid out in March of 1893 comprised nine holes, and could bad math have motivated Curtiss and Heard to change what Curtis had written?

Did they all assume that the 27 November 1893 Executive Committee minutes authorizing “the addition of three new holes” meant that three holes were to be added to six holes? Did such an assumption make them believe that Laurence Curtis had made a slip of the pen (a couple of times) when he said that he, Hunnewell, and Bacons had laid out nine holes?

And did they all think that the adding of the three new holes must have awaited the arrival of Willie Campbell in April 1894, rhetorically asking themselves: “who else could have added three new holes?”

Whatever motivated Curtiss and Heard, we can see that, regardless of what Laurence Curtis actually wrote, they were determined to make his essay support their assertion that the original golf course had six holes.

Figure 15 William Campbell (1862-1900). Golf, vol 1 no 26 (13 March 1891), p. 408.

Understanding the course laid out by Curtis, Hunnewell and Bacon to have been confined to six holes was also fundamental to their assertion that the first nine-hole course was not laid out until 1894, when they say that it was through the efforts of The Country Club’s first resident golf professional, William Campbell, that “the course was rearranged into our first nine-hole links” (p. 68).

According to Curtiss and Heard, that is, rearranger Willie Campbell (arriving at The Country Club at the beginning of April 1894) added three new holes to the original six holes of 1892 to create the club’s first ninehole course in the spring of 1894.

Similarly, in his 1914 talk to club members, Windeler indicates that it was “in April of … [1894] the course was extended to nine holes” (Boston Evening Transcript, 4 April 1914, p. 8).

As we shall see, however, there seem to have been at least two nine-hole layouts at The Country Club before Willie Campbell arrived, so it remains unclear why these historians of the earliest days of golf at The Country Club say that the first nine-hole course was laid out only after Campbell had arrived.

Boring

Curtiss and Heard imply that there is more to the story of the early golf courses at The Country Club than they tell in their book. And they confess that they deliberately decided not to tell this part of the story.

They explain that in writing their history of The Country Club, they limited what they would tell of the history of the earliest golf courses because they felt an obligation to write about more than “the Royal and Ancient Game” of golf:

it seems best to state at the outset various matters which [the authors] do not propose to treat in detail.

First, they do not propose to discuss the development of the golf course, hole by hole, bunker by bunker, tee to tee.

For the few readers who would find interest in such data, many more would be bored.

(The Country Club: 1882 – 1932, p. 62)

Bored!?

While understanding the practical decision made by Curtiss and Heard about how to construct their narrative, one can still regret their decisions: today, golf historians are legion who would cherish the “hole by hole” information that Curtiss and Heard chose to exclude from their narrative

The Unknown Original Nine-Hole Course

Proceeding upon the assumption that Laurence Curtis and the Boston Evening Transcript are correct in stating that nine holes were in play at the beginning of the 1893 golf season, we can see that we are missing a map of the original golf course at The Country Club: at best, the maps of a six-hole course presented by Windeler in 1914 and by Curtiss and Heard in 1932 show just two-thirds of the first course.

What do we know of the original course?

Well, to begin with, we know that there were nine holes.

More interesting, however, is the fact that we also know that these nine holes extended “more than a mile” (according to Laurence Curtis).

The course was definitely not two miles, and it was almost certainly not one and a half miles, or even one and a quarter miles, for (however odd it may seem to people nowadays) mid-1890s reports of the length of golf courses regularly specified the distance just as Curtis did: in terms of miles and fractions of miles. For instance, in 1895, the New York Sun reported that at the St Andrews Golf Club in Yonkers, “the course is fully one and one-half miles long,” and the year before, the Baltimore American reported that the Baltimore Golf Club opened “an excellent nine-hole course” that was “about a mile and a quarter in length” (Sun [New York], 16 June 1895, p. 16; Baltimore American, 30 November 1894, p. 6).

When he wrote his essay in 1895, Laurence Curtis was vice-president of the USGA and so he would have been thoroughly familiar with this way of discussing the length of a golf course. Since he said that the course was “more than a mile,” but did not say it was “one and a quarter miles,” we are probably safe in assuming that the original nine-hole golf course at The Country Club was just slightly over the 1,760 yards that make up a mile.

The nine golf holes, then, would have averaged approximately 200 yards in length.

Such an average length of hole today would suggest an “executive” golf course, but things were much different in 1893. As we know from the breathless report of a 150-yard drive at The Country Club in November of 1893 (“Tom Pettit, the champion tennis player of the B.A.A. [Boston Athletic Association], made a drive the other day of about 150 yards – a hopeless distance for an old or weak man to attempt”), the golf neophytes at the club were not hitting the ball very far during the first season of golf at Brookline (Boston Evening Transcript, 16 November 1893, p. 8).

A long-drive competition also conducted at The Country Club in November 1894 yielded only slightly longer drives from more experienced players:

It was required that the ball in its course should keep within a straight lane 40 yards wide.

R.J. Clark of the Country Club team exceeded his closest competitor by 13 yards. Mr. Clark’s winning ball was impelled 191 yards…. The trajectory was low, its highest point being estimated to be not more than 30 feet. The ball probably did not roll more than 40 or 50 feet at the end of its course.

F.J. Amory of the Essex County Club struck to a distance of 178 yards and R. Bacon of the Country Club fell short of this only six yards.

(Boston Globe, 3 November 1894, p. 4)

Of course, “R. Bacon of the Country Club” is golf course designer Robert Bacon. The best of his six drives in this November 1894 competition was 172 yards. Neophytes all when they took up golf in the fall of 1892, Bacon, Curtis, and Hunnewell will not have hit the ball even 172 yards when they began playing the game on Hunnewell’s links. Indeed, Curtis admits that they “were totally ignorant of the force and ‘carry’ and range of a fairly hit golf ball” (p. 125).

And yet, never having seen a proper golf course, and not knowing how far a well-hit golf ball might carry and then run (depending, of course, on which club was used), they would lay out a golf course. Curtis, Hunnewell, and Bacon would no doubt have regarded a hole of some 200 yards or so as a proper two-shot hole – and perhaps as a good 200-yard test of golf, at that!

Note, however, that by 1893, neither the concept of bogie nor the concept of par (which were regarded as virtually synonymous in the 1890s) had arrived in the United States, so these three men will have had no idea that a golf hole should be laid out at either one-shot, two-shot, or three-shot lengths.

As golf architect Walter J. Travis would explain a few years later, when conceiving a golf hole: “We will assume that we can drive from 175 to 210 yards; brassey, 170 to 190 yards; get from 150 to 180 yards with cleek or driving-mashie; 120 to 150 yards with a mid-iron, and lesser distances with a mashie. There is nothing extravagant in these distances with class players” (Golf, vol no 5 [May 1901], p. 355).

In the event, Curtis, Hunnewell and Bacon laid out alternating one-shot and two-shot holes across grounds that had been prepared for grazing horses, riding horses, and racing horses: their golf course was shared with a race track, a polo field, and a steeplechase course (a paddock would later become part of the course).

As Windeler later observed, “No place could have been less naturally adapted for the development of a good golf course than the property which The Country Club owns” (Boston Evening Transcript, 4 April 1894, p. 8). Certainly the “front land” before the clubhouse was relatively flat and featureless, devoid of natural hazards and therefore requiring that golf holes be routed across the artificial hazards of the race track and its railings, of the steeplechase course with its jumps and fences, and of the driveway or avenue to the clubhouse (note that a road was officially regarded as a hazard, the entire roadway bounded by the grass on either side of it being regarded as an area in which grounding the club was impermissible – whether on bare ground, gravel, pavement, or grass found between wheel tracks).

How can we tell how long the holes designed by Curtis, Hunnewell, and Bacon were? As seen below, the maps of the early courses provided by Curtiss and Heard are all drawn on the same background image of the club’s property, apparently using Windeler’s 1914 maps as a template.

Figure 16 The Country Club: 1882 - 1932, from left to right: pp. 69. 70, and p. 75.

Although no scale is indicated on any of the maps above, they are all drawn on identical backgrounds showing The Country Club grounds and they seem to depict accurately enough the relative lengths of the various golf holes.

Figure 17 The Country Club: 1882 - 1932, p. 75. Hole yardages have been added to the map according to the report in The Herald Statesman [Yonkers, N.Y.], 30 September 1895, p. 3.

Since we know the exact length of each of the nine holes depicted on the map of the “Extended & Lengthened 9 Hole Course,” we can make a reasonable determination of the length of the holes depicted on the diagram of the six-hole layout depicted by Curtiss and Heard.

On the Curtiss and Heard six-hole course map, there are three short holes (1, 3, and 5) and three long holes (2, 4, and 6).

Each of the three short holes is about the same length, and their length seems to have been about the same as that of the 108-yard 6th hole of the “Extended & Lengthened 9 Hole Course.”

All three of the longer holes were similar in length, too, comparable to the 285-yard 2 nd , 258-yard 4 th, and 268-yard 5 th holes of the “Extended & Lengthened 9 Hole Course.”

Curtiss and Heard’s claim that the crowd following the exhibition match on the course laid out by Curtis, Hunnewell, and Bacon “followed through the six-hole course, extending to more than a mile,” makes a nonsense of the maps in their book (The Country Club: 1882 – 1932, p. 66, emphasis added). If the six-hole course extended more than a mile, the holes would have averaged 300 yards in length, and yet not one of the holes shown on their map of the 1892 six-hole course reaches 300 yards in length.

According to the interpretation presented above of the scale of the Curtiss and Heard maps, the total length of the six-hole course shown by Curtiss and Heard would have been about 1,100 yards. Yet we know that Laurence Curtis indicates that the first course was about 1,800 yards long. And so, for the nine-hole course laid out in March of 1893 to have reached a total of “more than a mile,” the three holes not shown on the Curtiss and Heard map must have added up to about 700 yards. One might presume that the proportions of these three holes would have been similar to the proportions of the six holes shown by Curtiss and Heard and that these three holes also ranged from about 110 to about 280 yards in length.

Curtiss and Heard aver that when Curtis, Hunnewell, and Bacon laid out their course, “all of it [was] on the front land” (p. 31). Since Curtiss and Heard seem to have based this assertion on their apparent misunderstanding that their diagram of a six-hole layout represented the entirety of the layout by Curtis, Hunnewell, and Bacon, we cannot simply assume that the three other holes of their layout were also “on the front land.”

We know, however, that the 9th hole of the Curtis, Hunnewell, and Bacon layout was certainly located on this front land, for Laurence Curtis says that on the “course of nine holes” laid out in March of 1893, “the home hole [was] placed on the lawn in front of the clubhouse, in dangerous proximity, as after experience showed, to the front piazza” (p. 126).

The front lawn and the clubhouse piazza appear in the photograph below.

Figure 18 The Illustrated American, 20 June 1896, p. 831.

The sheep seen above were brought to The Country Club in mid-May of 1894 to keep the grass cropped low on the golf course and the polo field. In this photograph, the level part of the front lawn where the sheep are grazing may be where Curtis, Hunnewell, and Bacon laid out the green of their “home hole” in March of 1893.

Of course, this front lawn is where both the 1914 Windeler map and the 1932 Curtiss and Heard map (called “Original 6 Hole Course – 1892”) locate the home hole of the six-hole course. It would seem that the hole that Curtis, Hunnewell, and Bacon laid out in March of 1893 as their 9th is the hole that Windeler and Curtiss and Heard represent on their maps as the 6th.

Since the “home hole” remained the last hole of the original golf course – whether that course comprised six holes in the fall of 1892, as according to both Windeler and Curtis and Heard, or whether it comprised nine holes in the spring of 1893, as according to Laurence Curtis and the Boston Evening Transcript – a question remains: where had Curtis, Hunnewell and Bacon laid out the three holes not shown on the maps of Windeler and Curtiss and Heard.

Since the “home hole” was on “the front land,” and since the first hole remained more or less the same first hole on all three of the Curtiss and Heard maps of the 1892-95 courses (merely being lengthened on each successive map), perhaps Curtis, Hunnewell, and Bacon had found room for three more holes on “the front land” of The Country Club.

As the three holes in question were also relatively short, they might have been laid out in a number of places.

Did Curtiss, Hunnewell and Bacon lay out an additional hole or two across the race track?

Was there an additional hole on the polo field in front of the clubhouse? Were there other holes in the southern corner of the “front land” where the maps of Curtiss and Heard show the 5th, 6th, and 7th holes of Willie Campbell’s nine-hole layouts?

The 9th Hole of 22 April 1894

Note that there was a 9th hole on “the front land” of The Country Club in April of 1894. In fact, it was in playing this particular “home hole” that Arthur Hunnewell made the first and most famous hole-in-one at The Country Club.

Unfortunately, the old legend about this hole-in-one is inaccurate. It was said to have occurred not only on the very day in 1893 that Laurence Curtis organized for club members a demonstration of the new game of golf, but also on the very first shot taken during that exhibition match:

If legend and the memory of some of our eldest members is to be accepted [say Curtiss and Heard,] …. it seems that Mr. Arthur Hunnewell was the first to tee up, and, probably for the only time in his life, had the satisfaction of seeing his drive come to rest in the bottom of the cup.

The only reaction which this feat elicited from the gallery was a mild disappointment when he failed to hole his tee shot at the second hole.

They felt his game was not quite all that it should be!

(The Country Club: 1882 – 1932, pp. 66-67)

This story was always too good to be true.

But the hole-in-one shot heard across the decades was actually struck one year later than legend would have it:

Mr. Arthur Hunnewell has made by far and away the best drive made at the Country Club this season [1894].

He drove from hole 8 to hole 9, hole 8 being in the polo ground, over two fences and the race course and landing directly in the hole, a distance of 100 yards.

The first man did it in three drives [i.e. strokes], which was considered very good. The second did it in two, and then Mr. Hunnewell came along with a single drive, thereby beating all previous Country Club records.

(Boston Globe, 20 May 1894, p. 30)

Windeler reported to the club in his April 1914 talk that “It was … on April 22 [1894] that Arthur Hunnewell did the last hole in one stroke” (Boston Evening Transcript, 4 April 1914, p. 8).

Figure 19 Annotated detail from "The Country Club, Brookline, MA Horse jump." 1894. Photographer Nathaniel Livermore Stebbins. Historic New England: PC047: Nathaniel L. Stebbins photographic collection.

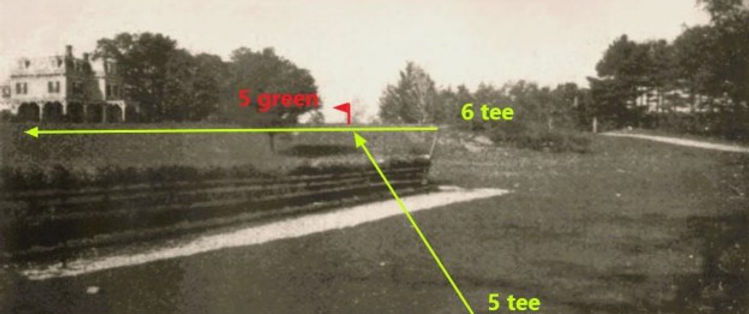

The phrase used in the newspaper that “he drove from hole 8 to hole 9” sounds a bit odd, but in 1894, the 9th tee box would have been chalked out very close to the hole marker on the 8th green. See, for example, the 1894 photograph on the left, which shows the hole-marker on the 4th hole and the chalk lines marking the nearby 5 th tee (beside which is the rectangular white sandbox from which sand was taken to make a tee for the ball.)

The hole-marker on the 8th green and the 9th tee would have been laid out in the same way.

In the 100 yards between the 9th tee and the 9th green were steeplechase “fences” (like those seen in the photograph above) as well as the race track in front of the clubhouse.

That Hunnewell achieved his hole-in-one while playing golf on a Sunday, which was regarded as scandalous by some club members (as well as by certain residents of Brookline), may have led him to mute his celebration, but three weeks later, the newspaper’s report of what he had accomplished provides invaluable information. We know that the polo ground and the race course across which Hunnewell was said to have played were located on the “front land” before the clubhouse. We know, then, that on 22 April 1894, the last two holes of a nine-hole course were located on “the front land” of The Country Club – precisely where Curtiss and Heard say the original course was entirely laid out.

Note, however, that the 100-yard 9th hole on which Hunnewell played on 22 April 1894 was not the 9th hole on which Willie Campbell and Willie Davis played less than four weeks later on 18 May 1894, for these two professionals played that day on a 9th hole that was 400 yards long: “on the ninth hole, … one must play over a gravel pit, past underbrush and hurdles, beyond apple trees in an orchard, with the hole four hundred yards away” (Boston Evening Transcript, 19 May 1894, p. 10).

Clearly, we have two very different 9 th holes in April and May of 1894.

Does this mean that there were at least two different nine-hole courses in existence at The Country Club at the same time?

Yes, indeed, it does mean this, as we shall soon see.

Moving the 9th Green

Before considering the nine-hole courses in play at The Country Club in the spring of 1894, we should note that the 100-yard 9th hole on which Hunnewell holed in one in April 1894 is not the approximately 260-yard “home hole” shown on the maps of the six-hole course provided by Windeler, on the one hand, and by Curtiss and Heard, on the other.

Recall that the location of the original “home” green laid out by Curtis, Hunnewell, and Bacon in March 1893 had proved to be dangerous to people on the clubhouse piazza. And so, at some point between March 1893 and April 1894, the original 9th green was “removed to a safer distance.” It may have been “removed” by 160 yards to the “safer distance” in question: that is, the original 260-yard 9 th hole of March 1893 may have been shortened by about 160 yards to become the 100-yard hole on which Hunnewell made his ace in April 1894 – the green simply having been relocated 160 yards short of the piazza.

It is not clear, however, precisely when this redesign of the original 9th hole occurred.

Laurence Curtis seems to indicate that play on the golf course was underway soon after the course was laid out in March of 1893. When he observes that “the home hole” was “placed on the lawn in front of the clubhouse, in dangerous proximity, as after experience showed, to the front piazza, and it was later removed to a safer distance,” he immediately says: “This was in April” (p. 126).

The referent of his pronoun “This” is not clear: what was it that occurred in April? Was it the removal of the 9th green to a safer distance from the piazza? Or was it the golf experience that showed that this green was too close to the piazza?

I suspect it was the latter: my guess is that Laurence Curtis was saying not that the original “home” green was moved in April, but rather that play as early as April had identified the danger that an errant shot could pose to people on the piazza.

How immediate was the danger?

Return to outdoor club activities each April was, of course, dependent on the weather, and so was the popularity of the piazza. And the volume of golf played at the beginning of 1893 was low, for adoption of the new game by club members unfamiliar with it was not quick. The Boston Evening Transcript reported in mid-May (more than six weeks after the course had been laid out) that “Few as yet do more than knock the ball about in desultory fashion” (Boston Evening Transcript,15 May 1893, p. 7). In the spring of 1893, not many people played the game. The reporter’s further observation in this mid-May article that “it is hoped that more will go in for golf and that the ladies will, by their approval, push along its popularity,” implies that Curtis had not yet determined that “the time had come to show the game to the members” (p. 126). He waited for a “day when there was a large number lunching” on the piazza and invited them to watch an exhibition of the game, after which he claims the enthusiasm was such that “all were golfers” (p. 126). No sign of that enthusiasm is evident in mid-May.

And a short while after the mid-May article mentioned above appeared in the Boston Evening Transcript, an article in the Boston Globe noted the very danger to members taking lunch on the piazza that Curtis mentioned:

Lunching at the Country Club while golf is in progress is full of pleasing uncertainty, much such an uncertainty as sitting in the window of a military prison when the guards have orders to “hit a head when they see it.”

A member of the club, not long ago, while peacefully eating his chops and green peas was missed by about two inches by a golf ball, which came merrily crashing through the window at his back.

How about iron shutters … until the players learn how to play?

(Boston Globe, 20 May 1894, p. 30)

And so, although the danger to diners posed by misplayed golf balls was known in May, moving the “home hole” seems not have occurred before June.

And by that point, summer was at hand, which meant that members departed from The Country Club: “Its activities continue all the year round, but as a large proportion of the members hie them to the seashore or elsewhere during the summer, its liveliest times are in the spring and fall” (Scribner’s Magazine, vol 18 no 3 [September 1895], p. 304). This abandonment of golf clubs and country clubs during the summer months was a tendency at most such clubs in the American Northeast in the 1890s.

And so, club managers accommodated themselves to this fact:

The Country Club, like a good many other of the best of Boston’s institutions – her parks, her suburban drives, etc. – suffers from the summer exodus.

Its “season” has to be arranged with a view to this “fashion” …. (Boston Evening Transcript, 15 March 1894, p. 4).

Not surprisingly, then, we find that the 1894 club championship tournament was scheduled for May and that the 1895 renovation and redesign of the golf course was scheduled for the summer months. Indeed, the summer was such a slow time for sports at The Country Club that at times, “in order to reduce expenses, the Golf Committee was instructed not to cut the grass during the summer months” (Curtiss and Heard, p. 67).

I suspect that when Laurence Curtis observes that the 9th green “was later removed to a safer distance,” he was referring to a much later event.

It might have been moved during the fall of 1893 or winter of 1894.

And it might have been Willie Davis who moved it.

The Addition of Three New Holes

According to Curtiss and Heard, the “first course was a six-hole affair, but in 1893 the club became more liberal, and, instead of continuing its original appropriation of $50, the Committee spread itself to the extent of $100 ‘for improving the course,’ and also authorized the addition of three new holes” (p. 68). They present here decisions by the Executive Committee as recorded in its official minutes, which Windeler indicates are dated 27 November 1893 (Boston Evening Transcript, 2 April 1914, p. 36).

Curtiss and Heard regard these minutes as supporting their claims that six holes were built and played on in the fall of 1892, that these holes served the club for almost the entire 1893 season, that at the end of November in 1893 it was decided that the six-hole course was “inadequate,” that it was also decided at that time that a nine-hole course would suffice, and that it was further decided that adding three new holes to the so-called original six would do nicely.

There was no hurry, mind you, about these new holes. Both Windeler, in 1914, and Curtiss and Heard, in 1932, imply that the work of designing and laying out these new holes awaited the arrival of the club’s first resident golf professional in April of 1894.

Yet, as Windeler notes, the Executive Committee’s decision to hire a golf professional was not made until January of 1894 (Boston Evening Transcript, 4 April 1914, p. 8). It seems rather back-to-front to approve adding three new holes five weeks before deciding that it would be a good idea to hire a golf professional to look after the matter. And in January of 1894, furthermore, there was no idea yet as to who that golf professional might be, let alone whether he would be capable of laying out a golf course.

Note, however, that we need not understand that approval of “the addition of three new holes” was for the purpose of bringing a six-hole course up to nine holes, as Curtiss and Heard believed (and as perhaps Windeler believed, too). I suspect that the Executive Committee approved adding three new holes to the original nine laid out by Curtis, Hunnewell, and Bacon – that is, approved bringing the total complement of golf holes to at least twelve.

Since all of the original nine holes had apparently been laid out on “the front land” before the clubhouse, the golfers were competing for space shared with polo players, horse racers, and steeplechasers. Routing three holes behind the clubhouse would help to relive the pressure on some of the space on “the front land.”

Don't Shoot!

Windeler contradicts his own assertion that the first nine-hole course was laid out in April of 1894 by citing Executive Committee minutes from 20 March 1894 that explicitly refer to a ninehole course in play at The Country Club a month before Windeler says that a nine-hole course even existed:

Even as early as early as 1894 there were complaints about congestion on the course, which was the beginning of a movement which resulted in lengthening and changing nine holes.

Golf, even then, though, was a minor sport at the club, as shown in the records, for on March 20 it was voted that the secretary write to the committee on shooting that until further notice, Thursday mornings and afternoons be set aside for shooting, during which time there should be no golf play on the regular seventh and ninth holes.

(Boston Evening Transcript, 4 April 1914, p. 8)

I suspect that the reporter may have made a slight mistake in the report above and that the minutes Windeler mentioned actually said, “there should be no golf play on the regular seventh to ninth holes” (emphasis added). Presumably, that is, golfers playing moving along the 8th hole from the 7th green to the 9th tee would also have been in the area of the shooting contest.

Whatever the case may be regarding the 8th hole, we know that by March of 1894, there was at least a 7th hole and a 9th hole that were too close to the clay pigeon shooting area for golf to be played safely on these holes when shooting was underway.

Where were these 7th, 8th, and 9th holes?

We know where the pigeon shooting occurred that would endanger golfers on at least holes 7 and 9. Shooting contests were held behind the clubhouse several hundred yards to the west. Dating from the opening of The Country Club in 1882, the pigeon traps and the purpose-built “shooting box” were located, according to Curtiss and Heard, in “what has to this day [1932] remained the quarry below the old tenth hole” (p. 89). The green of this 10th hole to which Curtiss and Heard refer was located near what is marked as the 9th tee on both of the Curtiss and Heard maps of the club’s nine-hole courses of 1894 and 1895. Note that the tee shot on the 9 th hole that Willie Davis and Willie Campbell played in May 1894 required a drive across this quarry (seen below).

Figure 20 The crater or quarry or gravel pit bunker at The Country Club in 1894. Harper's Weekly, vol 38 no 1977 (10 November 1894), p. 1077.

According to Curtiss and Heard, “standing with their backs to the stone wall …, they shot in the general direction of the clubhouse-end of the race track” (p. 89).

In addition to the 9th tee, there seems to have been a putting green located near the quarry in question, for the Boston Globe writer who visited the course in mid-May of 1894 reports: “One of the poles [that is, one of the putting green hole-markers] at the Country Club is near the traps where the members shoot clay pigeons, and on shooting days, playing golf behind the house is not wholly unattended with the exciting element of danger” (Boston Globe, 20 May 1894, p. 30).

Talk about hazards!

This putting green located near the quarry was no doubt the 8th green. On the one hand, we can be confident that the 8th green was near the 9th tee, which was on one side of the quarry. On the other hand, in the spring of 1894, the 8th hole was known as “Pigeon Hole” – obviously named for the pigeon shooting area in which it was located.

And so, by the time of the Executive Committee’s decision of 20 March 1894 to forbid playing golf on Thursdays on the holes near the pigeon shooting area, three holes had been laid out around the western and northern sides of the clubhouse: holes 7, 8, and 9. And we know that these holes were laid out by someone other than Willie Campbell, whose ship did not enter Boston harbour until 31 March 1899.

I presume that these holes are the three additional holes approved by the Executive Committee on 27 November 1893.

At this point, we have evidence of at least twelve golf holes in existence at The Country Club before Willie Campbell arrived in Boston. These twelve holes seem to have allowed for two ninehole circuits of play by March of 1894. There was the nine-hole Curtis, Bacon, and Hunnewell course, with its 8th and 9th holes laid out on the polo ground and racetrack in front of the clubhouse. And there was a course that concluded on the 7th, 8th, and 9th holes laid out behind the clubhouse to the west and north.

Perhaps six of the Curtis, Hunnewell, and Bacon holes served as the first six holes of this second nine-hole circuit.

Neither of these nine-hole courses is represented on the three Curtiss and Heard maps of the courses laid out at The Country Club between the fall of 1892 and September of 1895.

Willie Campbell's Extended and Lengthened Course

The Curtiss and Heard map called “Extended & Lengthened 9 Hole Course” represents a golf course laid out in 1895.

This new layout eventuated from the fact that bad greenkeeping practices during the fall of 1894 and winter of 1895 had ruined the greens: “it was demonstrated by last year’s experience that playing on the greens when frozen and then melted and then frozen again did them great damage” (Boston Evening Transcript, 9 November 1895, p. 4).

In the fall of 1895, therefore, the Golf Committee (Henry D. Burnham, Quincy A. Shaw, Jr, John T. Morse, and Laurence Curtis) instituted a new greenkeeping practice: “as soon as the frost sets in, the putting greens now in use will be laid up, manured, and play will be had on reserve greens” (Boston Evening Transcript, 9 November 1895, p. 4).

Ironically, two members of the Golf Committee (Shaw and chairman Burnham) were foremost among the winter golfers responsible for the damage to the greens at the beginning of 1895:

The word “season,” applied to duration of play at the Country Club course has almost the same significance as “perennial.”

It was only two days after New Year’s day that the golfers were in full swing driving the ball over the snow-encrusted course.

There were three of these early (snow) bird players, F.R. Allen, H.D. Burnham, and Q.A. Shaw, Jr. It was only for practice, but still one round was made in 49.

(Boston Globe, 10 November 1895, p. 2)

Play continued during the winter of 1895-96, mind you, but the regular greens were completely protected: “The Country Club golf course was much resorted to during Christmas week, and some very clever play was shown on the temporary greens, which for the time replace the regular link greens that are now covered over for the winter” (Boston Globe, 29 December 1895, p. 21).

The greens had been so badly damaged by play on them during the fall of 1894 and winter of 1895 that the golf course closed completely for renovation and redesign for almost the entire summer of 1895:

Country Club Golf Course Open

The summer’s golf work on the Brookline Country Club putting greens is now completed, and the full course is again open for play.

Active play will now be indulged in, particularly by those who will be practicing for the great contest against the St. Andrews Club on Saturday, Sept. 28.

(Boston Evening Transcript, 13 September 1895, p. 3)

The reference above to The Country Club leg of the home-and-away challenge match against a team representing the St Andrews Golf Club of Yonkers suggests that work on the course had taken at least a month longer than expected, for the match at Brookline had originally been planned for the second half of August but was not played until the very end of September.

Although during the winter of 1894-55 it was rumoured in London, England, that The Country Club was trying to hire James Braid, it re-hired Campbell and availed itself of the opportunity provided by the need to renovate the greens to mandate him to redesign certain holes, as shown by a comparison of the maps seen below (West London Observer, 16 March 1895, p. 6).

Figure 21 Comparison of the Curtiss and Heard diagrams showing early 9-hole designs at The Country Club reveals the holes lengthened by Campbell (the lengthening is highlighted in light green) and the holes where a dogleg was introduced to a fairway or removed from one (the dogleg is highlighted in light red).

The differences between the two layouts are not many, and most of the changes appear not to be very significant.

Campbell lengthened the course by relocating a number of tee boxes (particularly on the 1st , 4th , 5th, and 6th holes, and perhaps also on the 3rd), and perhaps by moving (by twenty yards or so) the location of the 3rd green. He may also have shortened the 2nd hole by moving the green by about twenty yards, and he also seems to have eliminated a dogleg fairway on the 2nd hole. But he introduced dogleg fairways on the 1st and 3rd holes.

The new “Extended & Lengthened 9 Hole Course” was 2,332 yards long.

On North American golf courses of the early 1890s, changing a tee box was the easiest way to lengthen or shorten a hole, for virtually no construction work was required: any area of level grass would suffice. The Country Club had an abundance of level grass areas, and on its golf course from 1893 to 1895 (as at Shinnecock Hills in 1891 and as at Newport in 1893, for instance), a tee box was made simply by marking out rectangular chalk lines.

The photograph below, for instance, shows the 5 th tee box in its location on the 1894 nine-hole layout: it seems to have been recently moved back several yards from a previous position to escape the divots created in its former location.

Figure 22 Faint rectangular chalk lines on the near side of the white sandbox mark the 5th tee box. Detail from “The Country Club, Brookline, MA. Horse jump.” 1894. Photographer Nathaniel Livermore Stebbins. Historic New England: PC047: Nathaniel L. Stebbins photographic collection.

As noted in an earlier section above, the 5th tee box was located not many yards away from the metal hole-marker on the 4th green.

Figure 23 Detail from “The Country Club, Brookline, MA. Horse jump.” 1894. Photographer Nathaniel Livermore Stebbins. Historic New England: PC047: Nathaniel L. Stebbins photographic collection. PC047.02.6020.05113.

Seen in the photograph above, the white wooden box placed beside the 5th tee was filled with sand, which (along with a container of water) was stored next to each chalked tee box so that golfers could take a handful or scoopful of sand for the purpose of constructing a conical pile of moistened sand on which the golf ball would be placed for the tee shot (the wooden tee peg would not become popular until the 1920s).

Note that the 5th hole was lengthened in 1895, probably simply by chalking out new tee box lines about thirty yards to the east of the 4th hole marker seen above (that is, about thirty yards further to the right of the ground at the right edge of this photograph). Moving the 5th tee box so far back meant that the new tee shot was played across the part of the 4th fairway and 4th green shown above.

Similarly, on the 1894 layout shown on the Curtiss and Heard map called “First 9 Hole Course,” the tee shot on the 6th hole crossed the fairway of the 5th hole. Campbell retained this routing on his extended and lengthened 1895 course, but he lengthened the 6th hole by moving the tee box back across the driveway that wound through the grounds.

The photograph below shows the view from the 5th tee box in 1894: the approximately 200-yard tee shot was played across the corner of “the steeplechase water jump” toward the putting green on top of the hill seen on the horizon, with the fifth fairway running alongside “apple tree hazards” on its right side (Harper’s Weekly, vol 38 no 1977 [10 November 1894], p. 1077).

Figure 24 Annotated photograph of the 5th hole at The Country Club in 1894. Harper's Weekly, vol 38 no 1977 (10 November 1894), p. 1077. The 6th hole was played at a 90-degree angle to the 5th hole. The shot from the 6th tee was played across the fairway in front of the 5th green.

The 5th hole ran from south to north, with the tee shot for the 6th hole played perpendicularly across the 5th fairway in an east to west direction, and so for three holes in succession, shots crossed the fairway of another hole, which must have led to slow play in this southwest corner of the course. Given that there was so much play on The Country Club course by 1896 that the first (unsuccessful) effort was made to organize the acquisition of new property for laying out a proper eighteen-hole course, one might suppose that the congestion caused here by the new Campbell design perhaps contributing to a lively awareness of the need for more space for golf.

Note that the names of holes in September of 1895 (seen below on the right) were the same as the names in May of 1894 (seen below on the left).

Figure 25 On the left is a newspaper report of the golf hole names that were in use by at least May of 1894; on the right is a report of the hole names (and yardages) at the end of September of 1895. (Boston Evening Transcript, 6 June 1894, p. 12; The Herald Statesman (Yonkers, N.Y.), 30 September 1895, p. 3.)

Yet although the names of the nine holes were the identical in the spring of 1894 and the fall of 1895, the lengths of certain of the holes were significantly different – and they were different in ways that the Curtiss and Heard maps of the 1894 and 1895 nine-hole courses do not account for.

"The Old Ninth Hole"

In September of 1895, the 9th hole of the extended and lengthened Willie Campbell course was known as “Paddock,” and it was 282 yards long (The Herald Statesman [Yonkers, N.Y.], 30 September 1895, p. 3).