Willie Davis and the Apawamis Golf Club’s 1899-1901 Redesign

Cover photograph of Willie Davis: Golf [New York], vol 10 no 2 (February 1902), p. 129.

CONTENTS

Introduction: Bendelow at First, and Then Bendelow Not So Much

The Bendelow Course Shrinks Towards a Do-Over

Golf History’s Second Accidental Davis Slight

Davis Does Without Cop Bunkers

Davis Limits Other Kinds of Cross Bunkers

Walter J. Travis and Strategic Design

Travis Plays and Thinks Apawamis

Stone Fences and Chocolate Drops

Introduction: Bendelow at First, and Then Bendelow Not So Much

After leasing land between 1896 and 1898 for its first and second nine-hole golf courses at Anderson Farm and Jib Farm, respectively, the Apawamis Golf Club became a first-time homebuyer at the beginning of 1899:

The Apawamis Golf Club of Rye, which has had a very pretty nine-hole course for the past two or three years, is now about to make a decided change.

The old lease expires April 1, and it cannot get a renewal at a reasonable rate.

The club has decided to purchase 120 acres of the Charles Park estate of Rye, where an eighteen-hole course, 6,400 yards long, can be laid out….

The outlay, it is estimated, for the purchase of the property, building of the clubhouse, and laying out the course, will be $100,000.

(Brooklyn Daily Eagle [New York], 27 February 1899, p. 12)

Called by some the “millionaire club at Rye,” the Apawamis Golf Club would spare no expense to create one of the best golf courses in the United States (Mount Vernon Argus [White Plains, New York], 15 May 1897, p. 1).

Figure 1 Thomas Bendelow, circa 1899.

News would emerge in the spring of 1899 that the club had hired Tom Bendelow (fast becoming the Johnny Appleseed of early American golf course design) to lay out its new course:

Thomas Bendelow has been consulted by the Apawamis Golf Club in regard to the planning of the new eighteen-hole course near the station at Rye.

The links, according to the Apawamis men, will be the best on the line of the New Haven Railroad between the City and Connecticut, a fact which they believe will make it very popular.

(New York Sun, 21 April 1899, p. 4)

Although Bendelow’s work at Rye was mentioned in the newspapers only at the end of April, he must have laid out the course in February, for within days of the February 27th report that “an eighteen-hole course, 6,400 yards long, can be laid out,” work on the course had begun: it was reported on March 2nd that “The course is now being laid out, and fine macadamized drives are being constructed through the property to connect it with the main thoroughfares of the village and to furnish convenient approaches for coaching parties” (Port Chester Journal, 2 March 1899, p. 4). By October of 1900, these “macadamized drives” may have been incorporated into the golf course as obstacles on two holes: on the 4th , there was “a road on rough ground on the right”; on the 8th, there was “a road” to be “carried with the drive” (W.G. Van Tassel Sutphen, Golf, vol 7 no 4 [October 1900], pp. 244, 245).

Several holes of the original Bendelow layout were described in relative detail at the beginning of March 1899:

The new property is well adapted for golfing purposes and there are so many natural hazards that there is no necessity for anything to be added in the artificial line. The stone fences which mark the line of the fields will serve most admirably for bunkers.

There is some very rough ground beyond the first and a ball which does not carry at least 125 yards will be badly punished, while the putting green is guarded by a wide brook, giving the golfers a very sporty hole to start with.

The second hole is also difficult, being a cleek shot over several abrupt hills to a blind green in the bottom of a punch bowl.

Most excellent use is made of a brook which guards the first green as it is crossed on six other occasions during the eighteen holes and in each instance forms a fine water hazard.

The property over which the links are spread is undulating and very inviting for golf purposes.

(Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 2 March 1899, p. 12)

On the redesigned course that opened for play in May of 1900, the first two holes described above would be so significantly lengthened through new green locations that one would be hard pressed to say that they remained Bendelow’s holes.

As Apawamis archivist, Robert A. Doto, pointed out in 2018, a detailed hole-by-hole course description in an “October 1900 story from the USGA publication Golf …. is consistent with the 1911 version [of the course] and our 2018 version,” yet, in his opinion, an early account of the length of each of the holes of the Bendelow design that appeared in a New York Journal article on 4 May 1899 indicates a layout that is “nothing like what we see today” (see Robert A. Doto, “Early Days of the Apawamis Golf Course,” July 2018, The Apawamis Club Archives, (https://www.apawamis.org/default.aspx?p=.NET_ArticleView&tview=0&plugid=1090427&ssid=3 27139&qfilter=RSC22481&itemID=314407).

Doto wonders “what happened between May 1899 [and] October 1900” (Doto, op. cit.).

Several things happened.

First, as it was under construction from February to October of 1899, the Bendelow course got shorter and shorter and original holes were modified.

Figure 2 William Frederick Davis (1861-1902), undated photograph. Golf (New York), vol 2 no 5 (May 1898), p. 16.

Second, in November of 1899, about a month after the Bendelow course was officially opened, the Apawamis Golf Club hired a golf professional named Willie Davis to turn the Bendelow layout into a championship golf course.

Unfortunately, about thirty-five years later, when Apawamis called upon the person who served as the Golf Committee Chairman from 1899 to 1902, Maturin Ballou, to write an account of how the original Bendelow layout was redesigned, he seems to have misremembered the name of the golf professional hired to do this work and instead introduced the name of another architect called “Willie” – but the Willie he named seems to have had nothing at all to do with Apawamis.

Unfortunately, ever since Ballou wrote that letter, William Frederick Davis has not received the recognition due to him for his role in designing the extraordinary golf course that is still played at Apawamis to this day.

The Bendelow Course Shrinks Towards a Do-Over

In February of 1899, the Bendelow course was planned to be 6,400 yards.

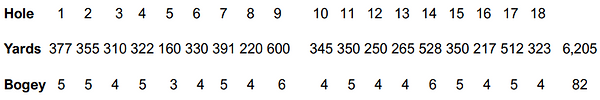

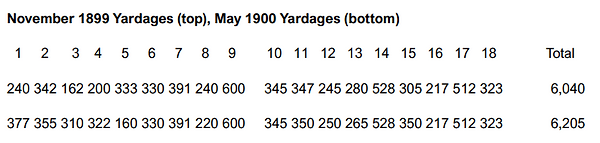

In November of 1899, the recently opened course (on which none other than Maturin Ballou set the amateur scoring record that month) was 6,040 yards.

Over the course of ten months, as a physical artifact, the golf course had become almost 400 yards shorter than it had originally been designed to be.

It turns out that Bendelow worked on this layout for many months and changed it many times.

We know that the original holes had been laid out by February of 1899. At the end of August, the New York Herald published an article called “New Golf Courses Near New York. Full Eighteen Hole Links to Open This Fall at Tuxedo, Rye and Elsewhere. Apawamis’ Fine Stretch”; regarding the Apawamis layout, the Herald reported that “‘Tom’ Bendelow is now busily engaged putting on the finishing touches to it” (29 August 1899). He was on site at various times over the course of at least seven months.

We know that the 6,400 original layout (described in newspapers on March 2nd) had been reduced in length by 11 May 1899, when work on the course was well underway:

The new eighteen-hole course of the Apawamis Club, at Rye, has been laid out by Bendelow, and already six of the greens are made.

It is to be 6,280 yards, making it one of the longest in the country.

Henry Cooper, treasurer of the club, said yesterday that the links will probably be finished and ready for playing on or about July 15.

(Port Chester Journal, 11 May 1899, p. 4)

The layout was now 120 yards shorter than originally planned.

We can see from the item cited above that the new eighteen-hole course was not expected to open before mid-July. For matches against other clubs in May and June of 1899, Apawamis planned to use its old nine-hole course on Jib Farm. Anticipating a July opening of the new 18- hole course, the New York Times reported: “the old course will probably cease to be used after this spring” (New York Times, 5 March 1899, p. 8).

But the old course may have been used far longer than expected, for the July opening of the new course never happened. In fact, the course would not open before the end of the summer – the New York Times later reporting that September 15th was the new target date: “everything will be in readiness to be used by Sept. 15, when the house and grounds will be formally thrown open with a tourney, either a club or invitation affair, which will last three days” (New York Times, 20 August 1899, p. 20).

When the New York Times wrote about the Bendelow course on August 20th, it indicated that the length of the course was still 6,280 yards, and it listed yardages for each of the eighteen holes that were identical to those listed in the New York Journal on May 4th . But by the fall, the length of the course was 6,040 yards.

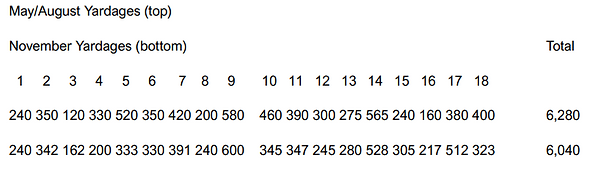

A comparison of the yardages for each hole as reported in both May and August, on the one hand, and as reported in November, on the other, is shown below:

Three of the November holes are quite different from the May/August holes: 4, 5, and 17 differ by more than 130, 187, and 132 yards, respectively.

Holes 1, 2, and 13, however, have virtually the same yardages, and holes 6 and 9 differ by just 20 yards. We may well have here the same holes in May/August and November.

In the fall, holes 3, 7, 8, 11, 12, 14, 15, 16, and 18 differ from their earlier lengths by between 29 and 77 yards: these November holes might be May/August holes made longer (in six cases) or shorter (in three cases). Or some of them may have been significantly redesigned. It is impossible to know for sure.

And so, the November yardages probably represent a combination of original May holes, slightly revised May holes, and several new holes made after 20 August 1899 – shortly after which Bendelow was reported on site again “busily engaged putting on the finishing touches to” the course.

I presume that the yardages reported in November (some of which are very different from the yardages reported in both May and August) were the result of these “finishing touches” apparently applied by Bendelow between the end of August and the opening of the course in the early fall.

Figure 3 Clearing stones March 1899 from Bendelow's new nine holes at Van Cortland Park, New York City. “Thomas Bendelow … began his labors on Monday of last week [13 March 1899], when he staked off the nine new holes and started a gang of workman at clearing up the course, picking off the loose stones and blasting the big rocks in the line of play” (Brooklyn Daily Eagle [New York], 19 March 1899, p. 9).

As superintendent of the Van Cortland Park public golf course, to which he had added nine holes beginning in March of 1899 in work that exactly paralleled his work at Apawamis, Bendelow was living and working less than twenty miles from Rye: up to the official opening of the new course, he could be on site virtually any day he was required.

It is reasonable to assume that the 6,040-yard November course is the one that Ballou describes in his mid-1930s letter as “our original layout” – a

Bendelow course that had been shortened and revised several times between its original conception in February of 1899 and its official opening in the fall of that year (Maturin Ballou, cited in William H. Conroy, Fifty Years of Apawamis [New York: Apawamis Club, 1940], p. 36).

Ballou’s explanation in his mid-1930s letter of how the “original” holes of the “original layout” were changed between 1899 and 1901 also makes clear that there was no other period of design between what he calls the “original layout,” which we know was produced by Bendelow between February and the fall of 1899, and the one produced by Golf Committee Chairman Ballou and the golf professional hired to assist him at the beginning of November in 1899.

Note Ballou’s description of the first two holes of the original course: “In our original layout, the first green was considerably short of the present one and to the left, near the present spring…. The second hole was at the foot of the hill on which our present green is now located” (cited in Conroy, p. 36). We know from what Ballou says here that the first and second holes of the original Bendelow layout were lengthened by Ballou and the golf professional who assisted him and we know that these two holes thereafter remained the first and second holes that have come down to the present day in pretty much the same form.

And note that Ballou reveals that the same is true of other holes: he indicates that the original fourth green was in a different location, identifies where “the original fifth hole” was located, describes how narrow the original seventh fairway was, explains how “the old ninth” tee was moved back and forth, indicates where the tenth and eleventh holes were “originally” found, and explains how “the original seventeenth hole” was problematic, and so on (cited in Conroy, pp. 36-38, emphasis added). In each case, he points to the original Bendelow hole and contrasts it with the hole revised by Bendelow and the professional hired to assist him – the hole that has come down to the present day.

There were just two periods of design between 1899 and 1901: the first between February and the fall of 1899, representing the original design work by Bendelow; the second between November of 1899 and January of 1902, representing the redesign work by Maturin Ballou and the golf professional hired to assist him.

Opening the Bendelow Course

Figure 4 The "Jib Farm" 9-hole course. Michael McCormack, "The Evolution of a Golf Course," Apawamis Now (Winter 2021-2022).

As we know, it was reported early in the 1899 golf season that “the club will continue to use the old nine-hole course until the new links are completed,” but precisely when the new 18-hole course opened for play is not clear.

The day before the August 20th New York Times announcement of a mid-September opening for the new course, the local golf report in the Daily Standard Union referred on August 19th to the “usual handicap” matches at Apawamis (Daily Standard Union [Brooklyn, New York], 19 August 1899, p. 20). Since the new course was not yet open, presumably this “usual” event – a “mixed foursome handicap sweepstakes” – was held on the old nine-hole Jib Farm course (Port Chester Journal, 17 August 1899, p. 4).

Then there was a “Women’s Handicap” held on the days of August 29th and September 1st , “fifteen holes to be played each day” (Port Chester Journal, 24 August 1899, p. 4).

And there were fifteen competitors on Labor Day in the “handicap sweepstakes for men” (Port Chester Journal, 7 September 1899, p. 4). Given, on the one hand, that Bendelow was on site putting “finishing touches” to the layout at the end of August, and given, on the other, that the New York Times’ anticipated a mid-September opening for the new course, one presumes that these late-August and early-September tournaments were also held on the old Jib Farm course.

There were no more club events reported for the month of September.

And so, it may be that Bendelow’s “finishing touches” required work on the new course throughout September. Such work may even have extended into October.

The New York Times had indicated in August that the club expected to open the new course and the new clubhouse simultaneously: “the house and grounds will be formally thrown open with a tourney, either a club or invitation affair, which will last three days” (New York Times, 20 August 1899, p. 20). It may well be, then, that the new course was opened at the same time as the new clubhouse was opened (with great fanfare) on October 7th:

The Apawamis Golf Club opened its new quarters at Rye on Saturday with a parade, band concert, informal reception, dinner and dancing.

The club house is 50 x 100 feet, Colonial style, over-looking the Sound.

The course is 6,400 yards. [presumably a typographical error, for by this point, the length of the course was 6,040 yards]

(White Plains Argus [White Plains, New York], 10 October 1899, p. 2)

After the Labor Day weekend events that were probably held on the old nine-hole Jib Farm course, the next club golf event seems to have been an October tournament, and it was held on the new 18-hole course. This event was a three-week match-play contest beginning late in October, with entrants qualifying for match play by means of a preliminary medal-play tournament:

On Saturday, October 21st, there will be an 18 hole medal play handicap for men on the Apawamis Golf Club links. The best 16 scores will qualify for match play.

The winner will receive a cup presented by the President of the Club.

The first match play round of 18 holes will be played on the morning of Election Day, November 7th, second round in the afternoon.

Semifinals and finals to be played Saturday, November 11th . (Port Chester Journal, 12 October 1899, p. 4)

We know from the description of a contest for a cup “given to be played for by the women members of the Apawamis Club” on October 31st that women were playing the new course 18-hole course – but not all of its holes: “Handicap match eleven holes, to be played either morning or afternoon, the first nine and the last two” (Port Chester Journal [New York], 26 October 1899, p. 4).

The final match of the men’s contest for the President’s Cup was deferred from November 7th to November 18th, and it produced an amateur course record for the new 6,040-yard course:

A new record was established for the Apawamis Golf Club links on Saturday by Maturin Ballou while playing the final match for the President’s Cup with F.H. Wiggin, whom he beat by 6 up and 5 to play.

The course is 6,040 yards long and Ballou covered it in 89 strokes.

(Brooklyn Daily Eagle [New York], 20 November 1899, p. 14)

This Bendelow course had taken the better part of a year to complete, but the Club never seems to have regarded it as satisfactory.

Flux

As we know, the yardages for the holes indicated in the New York Journal on 4 May 1899 are identical to the yardages indicated in the New York Times on 20 August 1899 – just before Bendelow was reported on August 29th to be on site applying “finishing touches” to the course. Bendelow seems to have been shortening the 6,280-yard May/August course even more, producing a playing length of 6,040 yards by the fall.

The state of certain holes seems to have been in such perpetual flux throughout the late summer and early fall that their playing lengths escaped reporting in contemporary newspapers. But thanks to Ballou’s mid-1930s letter, we know of the existence of these otherwise unrecorded holes.

For instance, Ballou says the original 13th hole was a “one-shotter” (cited in Conroy, p. 37).

He does not indicate the yardage of this version of the 13th hole. Note, however, that on the 6,280-yard version of the course, the 200-yard 8th hole was expected to take four shots to complete, so we know that it was regarded as a two-shotter. On that 6,280-yard course, the two one-shotter holes were 120 yards and 160 yards (New York Times, 20 August 1899, p. 20). And so, we know that Ballou’s reference to a one-shot 13th hole indicates that there was at some point a version of this hole that was significantly less than 200 yards.

Yet the 13th hole on the 6,280-yard course was 275 yards, and the 13th hole on the 6,040-yard course was essentially the same: 280 yards.

And so, there is no recorded version of what Ballou calls the original one-shot 13th hole.

Similarly, on both the 6,280-yard version of the course and the 6,040-yard version of the course, the 14th hole was 512 yards. Yet Ballou implies that there was at one time a shorter version of this hole: “the green, which was on the flat just across the brook, was moved back beyond the present green” (cited in Conroy, p. 37). We know, then, that the 512-yard hole was produced by a lengthening that came from moving the green back, yet there is no newspaper reference to the length of the “original” shorter 14th hole that preceded the 512-yard hole.

And Ballou says that “the eighteenth green was this side of the present green, but in the first year it was moved back” (cited in Conroy, p. 38). In other words, the original 18th hole was also lengthened by moving the green. Yet the length of the 18th hole both on the 6,040-yard course in the fall of 1899 and on the 6,205-yard course in the spring of 1900 was 323 yards. And so, the shorter version of the 18th hole to which Ballou refers also seems to have escaped mention in contemporary newspapers.

It seems that the Bendelow course never achieved more than a provisional final form, for it was being revised and redesigned perpetually throughout the spring, summer, and early fall of 1899.

Mixed Reviews

The Bendelow course had received good advance press.

From its first mention in the newspapers, it was anticipated that it would “be one of the finest in the country” (Port Chester Journal [New York], 2 March 1899, p. 4). The Apawamis Golf Club (“its membership … composed of New York millionaires”) “will overshadow every other club in the country and make even the New York millionaires envious at their golf links at Ardsley-on-the-Hudson” (Inter Ocean [Chicago], 12 March 1899, p. 41). Similarly, we read: “The links, according to the Apawamis men, will be the best on the line of the New Haven Railroad between the city and Connecticut” (Sun [New York], 21 April 1899, p. 4). The drumbeat of approval continued through the summer: “The golf grounds, it is said, will be one of the finest in the United States” (Port Chester Journal [New York], 27 July 1899, p. 4).

Late in August, the New York Times expressed hearty approval of the Bendelow design, characterizing it as a state-of-the-art accomplishment:

With all the expensive and carefully planned courses in this country … there are not a dozen which are laid out so as properly to penalize a poor shot, and to stop letting luck and not good play turn out the winner.

There are some courses, however, which are all that could be desired, and one which will shortly be added to that class is the new eighteen-hole links which the Apawamis Golf Club of Rye expects to throw open for play on Sep. 15. (New York Times, 20 August 1899, p. 20)

Yet for all the confidence in the Bendelow design that prevailed from the winter to the end of the early fall of 1899, Ballou indicates that there was almost immediate controversy about some of the original holes.

On the front nine, he noted that fairways on at least two holes were judged to be too narrow. And “there was a great deal of argument about the old ninth, the tee of which was moved back and then ahead and finally back again …. There was always a great deal of doubt as to the righteousness of this hole” (cited in Conroy, pp. 36-37).

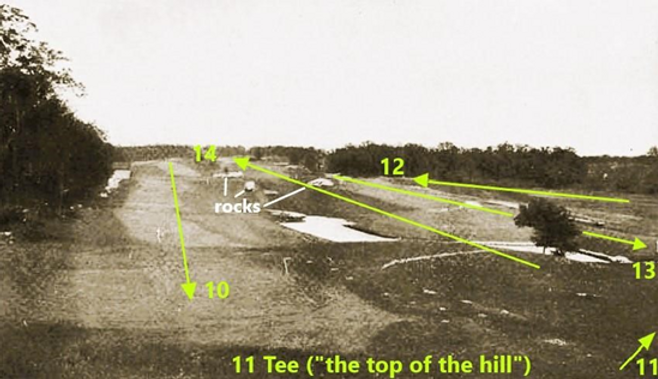

And the back nine, he observes, really needed stiffening. The 10th hole “was a comparatively easy par 4”; the 11th was “a very indifferent hole”; “the old thirteenth …. was a one-shotter and of no particular merit”; “the fifteenth was an easy two-shotter” (cited in Conroy, p. 37).

Most importantly, “the original seventeenth hole was a despair. The tee was at the foot of the hill and stretched across the entire fairway was a wide, deep trap. It took some years to correct this impossible hole” (cited in Conroy, p. 37).

It is no wonder that Ballou was eager to hire a golf professional to assist him with the redesign of the golf course.

A Draining Concern

That significant construction complications arose during work on the Bendelow course is implied by two things.

First, the opening date seems to have been continually deferred.

Granted, at the beginning of March 1899, the New York Times had heard from some Apawamis members that “in the Fall it is hoped to have an excellent eighteen-hole course in playable condition,” but it is clear that many more members anticipated a much earlier opening (New York Times, 5 March 1899, p. 8). These optimists told the Brooklyn Daily Eagle that they were anticipating they would be able to play golf on the new course by Decoration Day, May 29th (it is now called Memorial Day): “The property has been pasture land for some years and is covered with a rich turf, consequently it can be put in a playable condition, without much difficulty, before Decoration Day, when the club members are desirous of holding an informal opening” (Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 2 March 1899, p. 12).

We know, of course, that there was no golf at the end of May. The targeted opening date became July 1st. Then July 15th . Then September 15th. And then, perhaps, October 7th .

Second, as we also know, there was a continual reduction in the playing length of the course. The 6,400 yards planned in the winter became 6,280 yards by the spring, and then 6,040 yards in the fall.

Since the original layout seems to have been planned on a land bound by snow in February, it may well be that when the snow melted, Bendelow found conditions on certain parts of the course to be other than he had expected them to be. That is, since there were many swampy areas on the club’s new property, wet ground may have intruded into areas where Bendelow had originally thought he would be able to route some of his golf holes.

Note that in the fall of 1900 (a year after Bendelow had left the site), the property was still described as comprising a “Fair green of good old pasture sandwiched between boggy swampland and pebbly ridges” (Golf, vol no [October 1900], p. 242). Since in the fall of 1900, “boggy swampland” was still a prominent feature of the property – even after the installation in December of 1899 of what was characterised as a tremendously successful “new drainage system” – we may surmise that on the property acquired by the club at the beginning of 1899 (that is, well before a new drainage system had installed), there had been even larger areas of “boggy swampland” on the club’s property (New York Tribune, 29 January 1900, p. 9).

And even after the new drainage system was installed, of course, there remained low-lying areas and hollows prone to sogginess during periods of heavy rain.

It is certainly the case that by the end of the 1899 season, inadequate drainage of the property had become a significant problem, as suggested by the terms in which the new drainage system was celebrated at the club’s annual meeting at the end of January 1900:

As an instance of the care with which the new drainage system has been put in, it may be said that during and immediately after the recent heavy rain, coming upon the frosty ground, a combination usually fatal to a links, the course was playable and was played upon by many of the members.

(New York Tribune, 29 January 1900, p. 9).

By observing that now, even when the ground is frozen, heavy rain is no problem, the writer implies that the new drainage system has overcome a more serious difficulty that had prevailed hitherto: previously, heavy rain falling on ground that was not even frozen could make the course unplayable.

And so, It may be that Bendelow progressively shortened his original design at various points in 1899 because of drainage problems that progressively emerged as the seasons changed – emerged, that is, not just with the spring melt, but also when there were periods of heavy rain during the spring and summer.

That is, before the new drainage system was installed, perhaps it became clear that neither a 6,400-yard course nor even a 6,280-yard course was feasible along the lines of the original Bendelow routing.

In the fulness of time, Apawamis must have congratulated itself on the wisdom of exercising great care in installing the new drainage system, for (as fate would have it) heavy rain bedevilled the first big tournament played at Apawamis – the Metropolitan Golf Association Championship held in May of 1901:

“The recent rains left the course soggy in the hollows, while the putting greens were slow and not very true”;

[former U.S. Amateur Champion Findlay S.] “Douglas drove a high ball, which frequently buried itself in the ground”;

[the championship match was played in] “the most distressing weather conditions”;

“‘the rain spoiled matters just about as much as possible. The course was soggy and wet when they started, and rain soon began to fall. It ceased just as the morning round was finished but came down in torrents soon after the afternoon play was begun.”

(Brooklyn Daily Eagle [New York], 22 May 1901, p. 2; p. 2; 26 May 1901, p. 10; p. 10)

There can be little doubt that without the new drainage system, this tournament would not have been playable.

But the drainage system did its job, carrying water away and keeping the course playable every day: “The hard rain of last night left the Apawamis Golf Club links no better or no worse than it was yesterday” (Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 23 May 1901, p. 2).

The person responsible for the careful installation of this new drainage system was Maturin Ballou, who was by the end of 1899 being described as the “effective chairman” of the Golf Committee.

Maturin Ballou

As of May 1899, the official chairman of the Apawamis Golf Committee and thereby captain of the men’s golf team was prominent New York City real estate agent, appraiser, and auctioneer Herbert Augustus Sherman (1863-1919). It seems, however, that it was also in 1899 that Sherman “went into the real estate business” and immediately became busy and successful, which may explain why by the end of the year, one of the members of Sherman’s committee seems to have become the “effective chairman” in his place: Maturin Ballou (New York Tribune, 15 January 1919, p. 9; New York Tribune, 29 January 1900, p. 9).

In April of 1900, Sherman duly resigned as Chairman of the Golf Committee and was formally replaced by Ballou (although Sherman would continue to serve both on the committee and on the men’s golf team). Ballou would thereafter officially chair the Golf Committee until he was nominated to serve as Secretary of the United States Golf Association in January of 1902 (the same month, coincidentally, in which Willie Davis unexpectedly died).

Figure 5 Maturin Ballou (1853-1938). New York Tribune, 17 March 1902, p. 9.

Ballou had been born Levi Maturin Ballou in North Orange, Massachusetts, in 1853, a son of Reverend Levi Ballou and Mary Chase. In Franklin County, Massachusetts, he attended the co-educational Dean Academy (now Dean College) in the late 1860s and early 1870s, then enrolled in Tufts College (where his uncle had served as the first president). He was a keen athlete, playing throughout his time at Tufts for both the college football and college baseball teams, graduating in 1878. He also got married in 1878 and in the fall of the same year dropped his first name, legally changing his name to Maturin Ballou.

Ballou would live in Rye from the 1880s until about 1913 and then spent much of the year on a farm in Connecticut.

Although living in Rye, he worked as a broker in New York City, acquiring by the late 1890s an office at the prestigious address, 10 Wall Street. He served two years as secretary of the USGA from 1902 to 1904. Ballou died in Connecticut in 1938 but was buried neither in Connecticut nor in Rye, but rather back “home” alongside family members in Franklin County, Massachusetts.

From the early 1900s onward, Ballou was widely credited as the Apawamis official most responsible for the design of the present Apawamis course. In 1902, the Boston Globe observed: “Maturin Ballou … is a prominent member of the Apawamis Club of Rye, N.Y., and it is largely due to his efforts that the course of that club now ranks among the best in New York state” (Boston Globe, 30 March 1902, p. 36). In 1911, the club awarded Ballou an honorary membership in recognition of the fact that he was “instrumental in bringing the club links up to their … excellent condition” (New York Daily Tribune, 18 February 1911, p. 12).

As William H. Conroy (Club president from 1915 to 1927) observes in Fifty Years of Apawamis (1940):

Maturin Ballou, who was then Chairman of the Golf Committee, a proficient player and a man of vision, undertook the difficult task of developing from this large area the course over which we now play. How unusually sound was his judgement is evidenced by the fact that there have been comparatively few changes in the original design. (William H. Conroy, Fifty Years of Apawamis, 1940, p. 36)

Note that it was a habit in the 1890s and early 1900s for the wealthy members of golf clubs to give public credit for the “creation” of their golf course not to the lowly golf professional who designed it, but rather to the Chairman of their Golf Committee. After all, laying out the golf course and keeping the green were part of the job description of the golf professional in 1899. There was no such thing, yet, as a “golf course architect.” And so, although it was the golf professional who indicated where the tee should go, where the fairway should run, where the green should be located, and where the hazards should be placed, from the point of view of a golf cub’s managers of banks, businesses and investments, it was the club’s manager of this employee who deserved credit for the results of his work.

From the point of view of Apawamis members, then, it was Ballou who, as a member of the Golf Committee in 1899, participated in the hiring of the golf professional with whom he would work from 1899 to 1901 to redesign the Bendelow course. He deserved credit for that. And it may well be that by November of 1899, when Willie Davis was hired, Ballou was already acting as “effective chairman” of this committee and had taken the lead in hiring Davis. If so, he deserved even more credit.

Furthermore, as official Chairman of the Golf Committee beginning in the spring of 1900, he was the one who won approval from the club for the extensive redesign plans, and he was the one who regularly secured from the treasurer the funds necessary to keep the work going. So, of course, the Club accorded him an honorary membership in recognition of the fact that he was “instrumental in bringing the club links up to their … excellent condition” and the fact that it was “largely due to his efforts that the course … ranks among the best in New York state.”

But whether “proficient player” Maturin Ballou (who was accorded a handicap of 8 by the Metropolitan Golf Association in 1902) deserves credit for the sophisticated golf architecture introduced between 1899 and 1901 is another question altogether.

As Ballou himself acknowledged in the mid-1930s, he “was assisted” by a golf professional (cited in Conroy, p. 36).

Willie Dunn?!

Figure 6 Willie Dunn, Jnr, 1894. Dunn wears the medal awarded him as winner of the U.S. professional golf championship of 1894.

In his celebration of Maturin Ballou as “a man of vision” and “unusually sound … judgement” who “undertook the difficult task of developing … the course over which we now play,” Conroy quotes a letter written by Ballou “several years” before Fifty Years of Apawamis was published in 1940: “I was assisted by Willie Dunn, a young Scotch professional who came to this country to build the links at Shinnecock Hills” (cited in Conroy, p. 36).

Apart from Conroy’s 1940 quotation of Ballou’s mid-1930s letter, however, I can find no other document that connects Willie Dunn, Jnr, to Apawamis in any way.

We recall that regarding design work on the course between May of 1899 and October of 1900, Apawamis archivist Doto observes:

There are a number of stories, some documented, some shared from conversations with members over the years, about designers of our golf course.

Maturin Ballou, an important force during Apawamis’s early days at out current location, and Willie Dunn, a well-respected golf course designer, are generally credited with the design.

(Doto, “Early Days of the Apawamis Golf Course,” op. cit.)

A similar situation prevailed at the Shinnecock Hills Golf Club for a century. Willie Dunn was “generally credited with the design” until it was discovered that Willie Davis had come down from the Royal Montreal Golf Club in July of 1891 and laid out a nine-hole course for men and a ninehole course for women. Dunn did not arrive at the Club until May of 1893.

From the moment he first arrived in the United States, Dunn regularly made sure to provide news of his dozens of golf course designs to any newspaper he could think of. He was nothing if not a determined self-promoter. The fact would be remarkable, then, if, during Ballou’s three years as Chairman of the Golf Committee from 1899 to 1902, Dunn were to have designed a course for Apawamis and yet no contemporary newspaper or golf publication would ever mention him in connection with Apawamis.

Dunn, in fact, seems never even to have played the Apawamis course, let alone helped to design it.

Furthermore, contemporary newspaper references to the people who were responsible for the 18-hole Apawamis course mention just one golf professional as the original designer and just one golf professional as the redesigner:

The Apawamis course is situated about half a mile north of the Rye station ….

The property is the old Charles Park farm, consisting of about one hundred and twenty acres, and the financial outlay as the club appears today represents nearly $100,000.

The course was laid out two years ago by Thomas Bendelow and has since been improved and enlarged by “Willie Davis,” the man whom Apawamis players brought from Newport to aid them in securing a championship stretch of country.

(New York Tribune, 18 February 1901, p. 3)

Willie Dunn was well known to New York golfers by the time of this 1901 item, and, more important, he was extremely well known to the golf writers of all the main New York and Brooklyn newspapers, to whose offices he paid regular visits to make sure that his name stayed in the news. If he had ever been involved with the Apawamis design, it is surprising (to the point of being shocking) that his name is omitted from the above account of the designers of the course.

I suggest that thirty-five years after working with Willie Davis (thirty-five years during which Davis was thoroughly forgotten after his premature death), Ballou mixed-up the two Willies.

Is this possible?

Davis's Architectural Chops

In working with Willie Davis, Ballou was correct in recalling that he had worked at Apawamis thirty-five years before with a “professional who came to this country to build the links at Shinnecock Hills.”

As mentioned above, Davis had designed the first two nine-hole courses at Shinnecock Hills in 1891. Then there followed several layouts for the Newport Golf Club between Davis’s first arrival in Newport in November of 1892 and his departure for Apawamis at the beginning of November 1899: he laid out a nine-hole course on rented property in 1893; on new land that the club purchased subsequent to his recommendation, he laid out a nine-hole course (as well as a six-hole practice course) in 1894; he lengthened this nine-hole course in 1895; and he added nine new holes in 1897 to create Newport’s first 18-hole course.

And there were many other notable layouts.

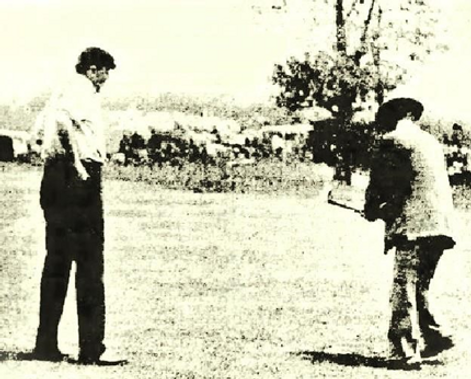

Figure 7 Golfers drive from the tee of the first hole (called "Oshkosh") of the 1891 Davis course of the Ottawa Golf Club. Collier's Once a Week, vol 11 no 45 (30 September 1893), p. 4.

Before his initial architectural venture in the United States at Shinnecock Hills, Davis had become famous in Canada for his “perfect greens” on Royal Montreal’s golf course at Fletcher’s Field. First laid out in 1873, eight years before Davis was hired, the course was re-laid several times on Mount Royal before Davis left for Newport in 1893 and Davis will have had a role in redesigning many holes. He also designed the first golf course for the Royal Ottawa Golf Club (Ontario, Canada) in April of 1891, and he may also have laid out at this time the new golf course for the reconstituted Kingston Golf Club (Ontario, Canada).

Several years after arriving at Newport, Davis listed in an autobiographical essay the courses that he had laid out in the United States between 1893 and early 1896:

Since I came to Newport, I have laid out links for the Country Club, Brookline, Mass.; Country Club, Providence, R.I.; Mr. Jas. Lawrence, Groton, Mass.; Dr. W. Seward Webb, Shelbourne Farms, Vt.; Messrs. Ogden Mills and W.B. Dinsmore, Staatsburg, N.Y.; at Hot Springs, Virginia; for Mrs. Wm. Goddard, East Greenwich, R.I., and George W. Vanderbilt, N.C.

(William F. Davis, autobiographical essay, undated, courtesy of Royal Liverpool Golf Club)

Davis’s list seems to be chronological: he laid out his nine-hole course for the Country Club of Providence late in the fall of 1893 or early in the winter of 1894; in Vermont, a nine-hole course was laid out for Webb early in 1894, with another nine holes added by Davis in the fall of 1895); begun in 1893 or 1894, the nine-hole Staatsburg course was opened for play in 1894 (anticipating the language of Ballou, a New York Evening Post article in 1896 says that this course was laid out by club member William Dinsmore, Jnr, assisted by Davis); Davis’s nine-hole Hot Springs course seems to have been laid out by the summer of 1894, when a newspaper referred to the imminent formation of a golf club in connection with the Hot Springs Hotel; his nine-hole course for Vanderbilt was laid out late in December of 1895 and early in January of 1896.

After 1896, Davis designed or redesigned several more layouts.

Figure 8 Thomas S. Barker, Spalding Golf Guide, 1898.

Early in 1898, he was called in to assist the local golf professional Thomas S. Barker in adding nine holes to the Chevy Chase golf course in Maryland. He continued to improve bunkers and tees on the course over the next two years.

In April of 1898, he was called to Wellesley College (Wellesley, Massachusetts), where the students at this women’s college had been playing golf since 1893, and where in 1898 it was said that the popularity of tennis “has been more than equally shared by golf perhaps …. There seems to be a larger number of young women at Wellesley whose collarbones are of masculine length and who can get a remarkably good swing of driver or lofter; and the tam and short golf-skirt are ubiquitous” (Times Union [Brooklyn, New York], 30 April 1898, p. 8).

Davis was said to be “getting the links in good shape for playing” (Boston Evening Transcript, 30 April 1898, p. 6). “Superintendent Davis of the Newport golf Club” is unlikely to have been called to Wellesley simply to perform greenkeeping duties; I suspect that he was asked to improve the layout (Boston Evening Transcript, 30 April 1898, p. 6).

Late in the summer of 1898, as the Morris County Golf Club prepared to host the U.S.G.A. Amateur Championship on its newly renovated course, “W.F. Davis” was celebrated as one of the four “professionals who have had most to do with planning it”: “It offers for the championship the most playable and the longest eighteen-hole course in this country and one that is better than many courses in Great Britain…. In brief, the championship course has arrived” (Sun [New York], 11 September 1898, p. 27).

In the fall of 1898, the Point Judith Country Club in Rhode Island decided to redesign its course: “Willie Davis of the Newport Club has been engaged to get the links in order…. The new course takes in four of the old and five new holes, which average about 300 yards” (Sun [New York], 14 June 1899, p. 9).

In the winter of 1899, in implicit acknowledgement of his high standing among contemporary golf course architects, Davis was commissioned by the USGA “to examine and report on all the golf courses available for either of the two national championship tournaments – the open and the amateur – for the coming season” (Baltimore Sun, 11 March 1899, p. 6).

In Baltimore, which hoped to host either the Amateur or the Open championship that year, excitement was great when Davis arrived in March “for the purpose of making a report to the Golf Association on the feasibility of using the links of the Baltimore Country Club for one of the national tournaments to be held by the United States Golf Association” (Baltimore American, 11 March 1899, p. 4). Club members were gratified by Davis’s generous extemporaneous comments on the day of his visit:

Mr. Davis, after going over the course, spoke in most enthusiastic terms about it.

He was so much delighted with the picturesque beauty of the links, the natural hazards, and the way the course is laid out that the members believe there may be a chance for the Country Club to get one of the national championship events.

The fact that the national association should consider Baltimore seriously enough to send Mr. Davis here to see the links … is considered a great compliment in itself ….

(Baltimore Sun [Maryland], 11 March 1899, p. 6).

There was a worry, however, that the golf course would be considered too short for a championship competition.

But Davis reported that “There is considerably more golf in it than you get on many golf courses that are much longer” (Golf [New York], vol 4 no 4 [April 1899], p. 2344). And he offered the USGA “his assurance that the total distance could be stretched to over 5400 yards” (Boston Evening Transcript, 18 March 1899, p. 20).

In fact, he planned the necessary changes himself: “W.F. Davis, professional of the Newport golf club, says he can lengthen the course at least 400 yards by moving back a number of the tees. The club has agreed to make the proposed alterations for the championship” (Standard Union, 16 March 1899, p. 8). Davis assured the USGA that “the character of the country is such that the distance of the course, as it will be, will equal any average course of 5800 yards” (Boston Evening Transcript, 18 March 1899, p. 20)

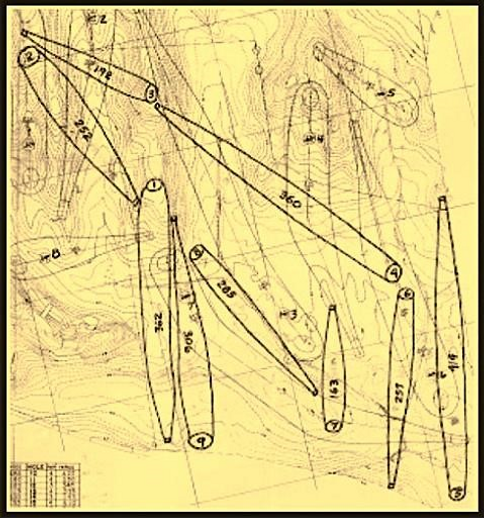

Figure 9 During the 1899 US Open, two golfers prepare to play from the 18th tee of the Baltimore Country Club course lengthened that year by willie Davis. Golf (New York), vol 5 no 4 (October 1899), p. 281.

Such was the USGA’s confidence in Davis that a week after receiving his report, it chose the Baltimore Country Club as the host of the 1899 US Open.

In 1897, after Davis added nine new holes at Newport to create the club’s first 18-hole layout, a Rhode Island newspaper noted: “Mr. Davis is one of the foremost … layout men in the business in America” (Evening Telegram [Providence, Rhode Island], 9 November 1897, p. 10). Five months after Davis moved to Apawamis and began his alterations on the course, the New York Times averred that “The name of Davis on a golf course is indication that the links will be worthy of a good test of golf” (New York Times, 11 March 1900, p. 20).

Clearly, since his first design work in the United States in 1891, Davis’s skill as a golf course architect had come to be widely respected and admired. It should be no surprise, then, to find Conroy declaring in Fifty Years of Apawamis that Davis’s premature “death in 1902 was a real loss, as he had done much to improve the layout” (p. 42).

Confusing Willies

As mentioned above, there seems to be no room for Dunn in the account of the creation of the present Apawamis golf course.

Bendelow was on site applying “finishing touches” to his layout at the end of August 1899. How long it took him to do this finishing work is not clear. Was he finished before the end of September? Willie Davis was hired by Apawamis during the first week of November. He was working at the club by 10 November 1899. After this, there was no need for any other architect’s advice, for Davis had laid out about twenty golf courses by this point, including the nationally renowned layouts at Shinnecock Hills and Newport.

What would have been the point of inviting Dunn to Apawamis after Bendelow left in September or October of 1899, only to replace any possible Dunn influence several weeks later with that of the celebrated architect and newly arrived resident golf professional, Willie Davis?

I think the more likely explanation is that when Conroy asked Ballou – shortly before the latter died in 1938 at eighty-four years of age – to write about the redesign of the original Apawamis course, Ballou misremembered the name of America’s first golf professional, Willie Davis, as that of America’s second golf professional, Willie Dunn, who in the interim had become much more famous.

When Ballou wrote in his mid-1930s letter, “I was assisted by Willie Dunn, a young Scotch professional who came to this country to build the links at Shinnecock Hills,” he was correct in recalling that he worked with the “professional who came to this country to build the links at Shinnecock Hills” – but that professional was Willie Davis. When discussing ideas with Ballou regarding the Apawamis redesign between 1899 and 1901, Davis no doubt mentioned to Ballou some of the things he had done at Shinnecock – thereby cementing in Ballou’s mind the connection between Shinnecock Hills and the golf professional named Willie who had assisted him thirty-five years before.

If Ballou indeed subsequently mixed up Willie Davis and Willie Dunn, he made the same error as Shinnecock’s founding member Samuel L. Parrish when the latter was asked in the early 1920s to write up for the Shinnecock Hills Golf Club his recollections of the laying out of Shinnecock’s original course more than thirty years before. Although Parrish had personally worked with Davis as the latter inspected Shinnecock Hills sites in 1891, thirty-two years later, he misremembered his name as Dunn.

Indeed, it is possible that Ballou was familiar with Parrish’s account of the founding of Shinnecock Hills and was accidentally led by Parrish to mix up the two early pioneering Willies in the same way.

Golf History's Second Accidental Davis Slight

If I am correct in my surmise that in his old age, Ballou misremembered his old golf professional’s name as Dunn rather than Davis, he was thereby accidentally responsible for American golf history’s second slight against Willie Davis, for, as mentioned above, exactly the same case of mistaken identity had occurred at Shinnecock Hills a decade earlier, with the same result: Davis’s fundamental role in laying out an iconic golf course was obscured for a century.

In the early 1920s, when the president of the Shinnecock Hills Golf Club asked Samuel L. Parrish, one of the few founding club members still alive at that time, to share his recollections of the origins of the golf course more than thirty years before, Parrish mistakenly attributed the original design to Willie Dunn:

We asked the late Charles L. Atterbury, who was about to visit Montreal on a business trip, if he would interview the authorities of the Royal Montreal Golf Club (organized in 1873, the oldest golf club in Canada, and therefore in the western hemisphere) and arrange with them to have their professional come to Southampton and look over the ground.

As a result of this interview, the scotch-Canadian professional, Willie Dunn by name, arrived at Southampton with clubs and balls in the early part of July, 1891, consigned to me.

Immediately upon his arrival, we drove out to Shinnecock Hills but had proceeded only a few hundred yards … when Dunn turned to me and remarked in a somewhat crestfallen manner that he was sorry that we had been put to so much trouble and expense, but that no golf course could be made on land of that character.

We had already turned our faces homeward toward Southampton when I said to Dunn: “Well, Dunn, what do you want?” …. He then explained that ground capable of being turned into some sort of turf was necessary …. I then drove him to a spot in the valley … composed of sandy soil comparatively free from brush and capable of some sort of treatment appropriate for golf at a reasonable outlay of time and money.

(Samuel L. Parrish, Some facts, reflections, and personal reminiscences connected with the introduction of the Game of Golf into the United States, more especially as associated with the formation of the Shinnecock Hills Golf Club [privately printed by Samuel Parrish, 1923], pp. 5-6)

The Montreal golf professional in question was of course Willie Davis, as Parrish himself well knew when he told the very same story – this time correctly – to the New York Times in 1896, less than five years after his day spent with Davis:

Mr. Atterbury, who had learned something about the celebrated Scotch professional, Willie F. Davis, now at the Newport Golf Club, but who at the time had charge of the Montreal Golf Club course, suggested that the Shinnecock Club secure the services of Willie Davis to lay out a course in the vicinity of Southampton. Davis was accordingly requested to come down and look over the sand hills of Long Island and pass his opinion upon their golfing merits.

He did not at first sight launch forth into eulogies of their similarity to the old St Andrews course in Scotland…. That portion of the Shinnecock Hills over which Willie Davis was first taken did not meet with his favor at all.

Mr. Parrish, in telling the result of this walk over hills, says that at one point, Willie Davis was anxiously asked what he thought of the grounds, [where] there was a large growth of underbrush, particularly thick. “With a sad voice and troubled look, Willie Davis replied,” Mr. Parrish said, “‘Well, Sir, I don’t think you can make golf links out of this sort of thing.’”

At this point, however, it was suggested that they visit the hills across the railroad track … where the ground had more of the qualities of a sandy turf, and it was while viewing this section … that Willie Davis’s face lighted up, and with true golfing ardor he exclaimed: “This is more like it.”

(New York Times, 8 March 1896, p. 25)

Davis was on the Shinnecock site for between four and five weeks in July and August of 1891, residing in a nearby cottage as he supervised members of the Shinnecock Indian tribe in the laying out a nine-hole course for men and a shorter ladies’ course of about 1,800 yards.

Figure 10 Some days ago ... I drove over to the farm house near Southampton which Mr. Davis has made his temporary home and induced him to escort me to the links he has planned out at Shinnecock …. In half an hour or so, we halted on the brow of a low hill just below the well-known windmill. Here Mr. Davis directed my attention to a round green clearing twenty-five or thirty feet in diameter. “This,” said he, in tones which sounded strangely solemn,” is a putting green. We golfers hold it sacred as a sanctuary.” (New York Herald, 30 August 1891)

The New York Herald sent a reporter to interview Davis. She was very impressed by the young golf professional, whose instruction in the game led her to overcome her scepticism about golf: “A professor at St Andrews once defined the game as ‘knocking little balls into little holes with clubs extremely ill adapted to their purposes’ …. I have shared the vulgar view myself, and it was only this week that I recanted, after taking a hand in an informal game on Long Island under the skilled guidance of that prince of golfers, Mr. Davis” (New York Herald, 30 August 1891).

Figure 11 "W.F. Davis, the Crack Golf Player." New York Herald, 30 August 1891.

In the summer of 1891, Davis’s work to develop grounds for this exotic foreign game was of such interest that the newspaper had Davis sit for a portrait by its sketch artist (seen to the left).

Yet so widely was Parrish’s inaccurate 1920s narrative disseminated, and so authoritative did his mistaken recollection thereby become, that Willie Dunn was credited as the original architect and Willie Davis’s responsibility for the original golf courses was entirely forgotten. It took almost ninety years for Shinnecock Hills to correct the record.

Parrish had personally accompanied Davis around Shinnecock Hills as Davis inspected possible golf sites, and Parrish had personally interrogated him about what was requisite for the construction of proper golf links.

And, not surprisingly, he had a perfect recollection of Davis’s name five years later when he recounted the events of 1891 to the New York Times. Yet thirty years later, he confused Davis with Dunn.

Similarly, Ballou worked with Davis on the redesign of Apawamis from 1899 to 1901. He even served as a pall bearer at Davis’s funeral in 1902. Yet more than thirty years later, he, too, seems to have confused Davis with Dunn, also obscuring – for more than a century – Davis’s fundamental role in the design of the Apawamis course that is still played today.

It is not too late to set the record straight.

Assisted by a Professional

Davis had laid out or redesigned some twenty golf courses in North America by the time he met Ballou in 1899, so we know which of them had the greater knowledge and experience of golf course architecture and construction when they began working together at Apawamis that year.

Ballou has been regarded by the Club as the main designer of its remarkable layout, but his mid-1930s letter about the Apawamis redesign between 1899 and 1901 does not come across as written by a person with much interest in or sophistication about golf course architecture. He describes the many changes that were made, but he is curiously silent about architectural motivations for them.

Ballou notes that fairways on at least two holes were judged to be too narrow. And he notes that the tee box of the 7th hole was moved to increase the angle for entering the 7th fairway. Apart from these hints regarding architectural concerns, he merely lists changes: a tee was here first and then it was there; a green was here first, and then it was there; a hole originally took one shot, and then it took two.

For instance, he remarks that “there was a great deal of argument about the old ninth, the tee of which was moved back and then ahead and finally back again …. There was always a great deal of doubt as to the righteousness of this hole” (cited in Conroy, pp. 36-37). But he sheds no light on the nature of the debate about the architectural “righteousness” of this hole. What were the golfer’s arguing about?

And his observations about how several holes on the back nine needed stiffening – the 10th hole “was a comparatively easy par 4”; the 11th was “a very indifferent hole”; “the old thirteenth …. was a one-shotter and of no particular merit”; “the fifteenth was an easy two-shotter” – provide no insight into how these holes were thought to be architecturally deficient or how these deficiencies were addressed by better architecture (cited in Conroy, p. 37).

Similarly, his observation that “the original seventeenth hole was a despair” – “The tee was at the foot of the hill and stretched across the entire fairway was a wide, deep trap” – does not offer an explanation of its architectural deficiency, and his remark that “It took some years to correct this impossible hole” provides no hint as to how the hole’s architecture was corrected (cited in Conroy, p. 37).

Writing in the mid-1930s, not only does Ballou not sound like an architect; he does sound as though he ever thought like one. If Willie Davis had lived long enough to have been asked to write about the Apawamis redesign of 1899-1901, I imagine that he would have mentioned architectural reasons for the changes made to the Bendelow design.

In fact, at the time of the 1899-1901 redesign, the golf writer for the New York Times seems to have talked to Davis about the new course and Davis seems to have explained why the opening holes were being redesigned:

Professional Willie Davis is still at work on the greens, and until May 1 temporary ones will be in use.

Some changes in distances of the first few holes are being made, so as to prevent an overcrowded condition on the links on big days.

The first hole is being lengthened to 375 yards, from 240 yards, and this will ensure more speed in getting players off.

(New York Times, 22 April 1900, p. 9)

Architects have always thought about how a first hole should be designed to get a round of golf underway, and Davis seems to have been no exception. Note that Davis explained why the first hole was lengthened, whereas Ballou observed only the fact that it was lengthened: “In our original layout, the first green was considerably short of the present one and to the left, near the present spring” (cited in Conroy, p. 36).

I suspect that this was the relationship between Davis and Ballou: Davis explained the need for changes; Ballou received the explanation and decided whether the changes would be made.

And so, I suggest that the primary redesigner of the Apawamis layout was Willie Davis and that Ballou, as Chairman of the Golf Committee, was credited with the design because “his efforts” were so “instrumental” in getting the course made.

In 1897, this sort of relationship obtained at the Newport Golf Club between Davis and the Chairman of its Green Committee, A.M. Coates. But the latter gentleman was celebrated more than the golf professional for the creation of the new layout:

The Newport Golf Club is now having its links extended [by nine holes] and by the middle of July, when the work of alteration is expected to be finished, members and visiting players may play over a links second to none in this country.

The course was laid out by W.F. Davis, the resident professional and clubmaker, and approved by A.M. Coates of the Greens Committee, who has made it his business to look after the condition of the grounds and to everything pertaining to the welfare of the sojourning players of this classic summer resort.

Mr. Coates has gone abroad, but before leaving he went carefully over the details of change and expressed his belief that it would be a fine sporting course and that visitors coming here for the open tournament in the early fall will have ample opportunity to use every club in their set as a round of the links calls for an endless variety of golf.

(The Golfer, vol 5 no 1 [May 1897], p. 21)

Newport members will have regarded Coates just as Apawamis members regarded Ballou: as a proficient player (Willie Davis regarded Coates as the equal of 1895 US amateur Champion Charles Blair Macdonald) and as a man of vision (with unusually sound judgement about golf course design). But today, of course, architects and golf historians alike regard Davis, and not Coates, as the designer of Newport’s 1897 course.

In the pages that follow, I treat the primary architect of the Apawamis redesign of 1899 to 1901 as Willie Davis, rather than Maturin Ballou.

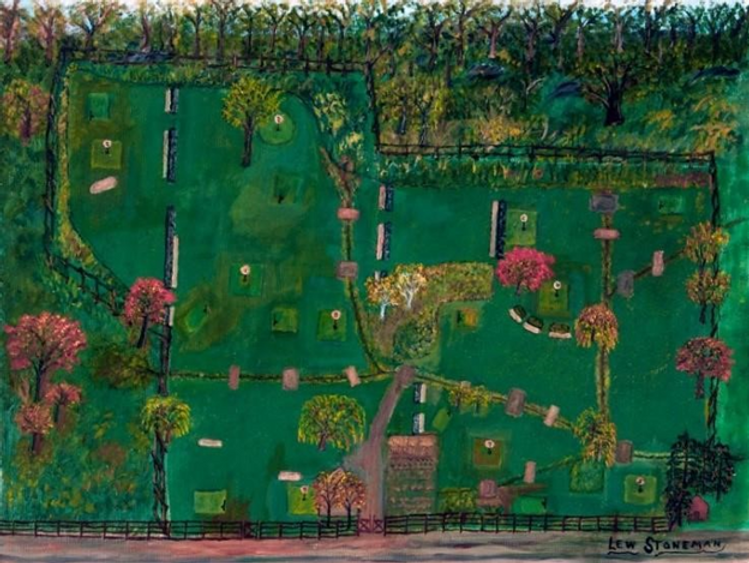

New Drainage and New Holes

Solving drainage problems seems to have entailed substantial grading work on certain parts of the property:

The Apawamis Club grounds are well adapted for championship games; it is one of the longest and is the finest course in the country.

The large grounds, which a few years ago were used as farm land, have been graded and remodeled until today they are like a vast lawn extending far from the clubhouse over the green hills to the valley beyond.

(Port Chester Journal [New York], 23 May 1901, p. 4).

This grading and remodeling must have produced new slopes and ditches designed to move water across the property – slopes and ditches that would have constituted a new terrain over which and through which certain of the original Bendelow holes would have had to have been rerouted.

Observing that “With all the expensive and carefully planned courses in this country,… there are not a dozen which are laid out so as properly to penalize a poor shot, and to stop letting luck and not good play turn out the winner,” the New York Times acknowledged that “There are some courses … which are all that could be desired, and one which will shortly be added to that class is the new eighteen-hole links which the Apawamis Golf Club of Rye” (New York Times, 20 August 1899, p. 20). The newspaper’s point is that Bendelow’s course had been designed on rational, scientific principles: the hazards were disposed on each hole at distances from tees and greens proper for the purpose of penalizing certain badly played shots.

Adding ditches to the land across which the Bendelow course was laid out would add hazards in places that Bendelow had not placed hazards and had not intended hazards to be found. Shots would now be penalized (by new slopes and ditches) that were not meant by Bendelow to be penalized. Unless the golf course were redesigned, it would no longer be a rational, scientific layout.

Similarly, significantly changing the length of a hole on Bendelow’s celebrated layout would change the way the existing hazards functioned on this changed hole. First, lengthening or shortening a hole would change the location of hazards relative to the tee shot. Second, on a lengthened or shortened two-shot hole, the subsequent approach shot would also be lengthened or shortened, changing the golfer’s challenge in relation to fairway hazards placed between the golfer and the green, on the one hand, and changing the golfer’s challenge in relation to hazards surrounding the green, on the other.

To make the disposition of hazards rational and scientific on a property with new slopes and drainage ditches, Ballou recognized that he would need the assistance of a golf professional.

Apawamis Ambitions

The first Amateur Championship of the Metropolitan Golf Association was conducted in April of 1899. The Apawamis Golf Club was ambitious to be recognized within the Metropolitan Golf Association as one of the best clubs – with one of the best golf courses – and so, it was eager to host a future MGA Championship tournament on its new course. Since the best and most accomplished amateur golfers in the United States at this time were members of the MGA, this championship tournament was second in standing only to the USGA Amateur Championship itself.

To be competitive with its bid for this honour, however, the Club knew that the question of proper drainage and the question of proper length would have to be addressed.

Fearing that golf clubs would be reluctant to dedicate a week to a championship tournament during the summer months (the busiest part of the golf season), the MGA had decided that it would stage its championship in May, and so, in determining the site each year of its championship, the MGA sought not only an eighteen-hole golf course of championship length, but also a course that was dry in the spring:

In regard to the championship course, it is generally understood that the Apawamis links, of Rye, will be the one selected.

This course offers an opportunity for early play – something the Association has always insisted on – while recent improvements there brings it within the requirements of a championship links.

(New York Tribune, 28 January 1901, p. 8).

Without proper drainage, there would have been no possibility of “early play” at Apawamis, and it seems that only because of the unspecified “recent improvements” made by Davis had the club’s eighteen-hole course now come to be regarded as a “championship links.”

These “recent improvements” had been undertaken in the fall and winter of 1899-1900:

The Golf Committee, under its effective chairman, Maturin Ballou, has had a large force of laborers at work all winter and recent changes and improvements have brought the total playing length up to 6,200 yards.

William F. Davis, formerly with the Newport Golf Club, is the club’s professional, and under his care the links promise to be the best in the State by another season.

(New York Tribune, 29 January 1900, p. 9).

The “changes and improvements” had no doubt been planned in conjunction with “the new drainage system.”

As suggested in the previous section, it was probably recognized by the club that the work of properly draining the course would not only allow a re-laying of certain golf holes through newly drained areas but would also require the re-laying of certain golf holes to make their hazards rational and scientific – “rational and scientific,” that is, according to the tenets of penal architectural theory.

Penal Architectural Theory

Following the tenets of the penal theory of golf course architecture that prevailed in the 1890s and early 1900s, golf architects made sure to arrange for each hole at least one hazard (whether natural or artificial) stretching across the entire width of the fairway. On a two-shot hole, a second fairway-wide hazard would be placed between the golfer and the putting green – often directly in front of the green. And there was generally an additional fairway-wide hazard to be crossed on a three-shot hole.

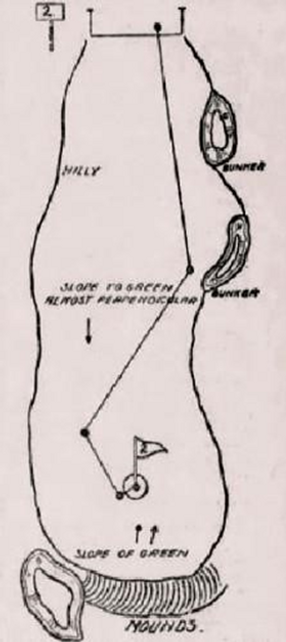

Note the following 1901 “suggestions by an expert on constructing hazards” in a newspaper article called “Bunker Building on American Links”:

Take a 150-yard hole …. If there are no natural hazards, it is advisable to place two copbunkers 110 yards from the tee, side by side clear across the course. About one-fourth of the bunker in front should overlap one-fourth of the other, leaving a path [for golfers] running sideways, and not straight for the hole, to prevent balls rolling through. Each of these bunkers should cover one-half of the width of the course. The trap should be twenty feet wide and two and one-half feet deep, while the height of the cop should be three feet….

Figure 12 Along the lines of those described above, a series of inked cop-bunkers (designed in 1901 by Walter J. Travis and John Duncan Dunn, a nephew of Willie Dunn, Jnr), with a sand-filled ditch in front of each, crossing the entire 8th fairway at the Flushing Country Club. Golf (New York), vol 9 no 1 (July 1902), p. 11.

For a hole 340 yards long, the theoretical arrangement of artificial hazards would be:

Place two bunkers two feet deep, end for end eight[y] yards from the tee, with cops eighteen inches high to catch topped or foozled drives….

For variety, and in order to add to the picturesqueness of the course, mounds [instead of cop bunkers] are sometimes erected to guard the green. They should be placed 285 yards from the tee, and built about six or eight feet in height, twelve feet wide, and extending almost across the course. The end of one mound should overlap the other with a patch between, sunning sideways [for golfers to walk through] ….

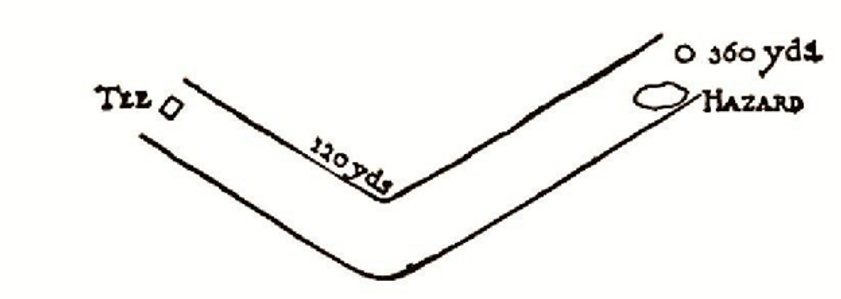

Figure 13 Willie Davis's overlapping cop bunker mounds on the 5th hole of the Newport Golf Club, 1895. Frederick Waterman, The History of the Newport Country Club (Newport, Rhode Island: Newport Country Club Preservation Foundation, 2013), pp. 118-19.

The player who can consistently negotiate a 500-yard hole laid out as follows in anything like bogey figures should make a dangerous opponent:

[First] Build a cop in two sections about three to five feet high, with a shallow bunker in front, extending across the course about fifty yards from the tee….

[Second] About 240 yards from the tee, it would be advisable to place a cop bunker twenty feet wide, three feet deep, and as long almost as the width of the course will permit….

[Third] Within fifty yards of the hole, an ordinary cop-bunker should be placed clear across the course to protect the green.

(Inter Ocean [Chicago], 19 May 1901, p. 49)

A person playing a golf course for the first time could tell the par of any hole by counting the number of cross bunkers on it: par equals the number of cross-bunkers plus two strokes for putts.

The idea was to punish golfers who could not get the ball into the air to carry it over these obstacles, for the general conviction, at a time when championship golf was almost exclusively decided by match play, was that it was unfair on a two-shot hole, for instance, to allow players first to top a drive and then top a fairway shot and thus roll a ball all the way to the putting green with two bad shots, thereby still having a chance to be “level” with the player who had reached the green with two perfect sots. Such a hole was called a “leveller” hole, and it came to be despised by scratch players and golf architects alike.

And so, at Apawamis, new ditches that had been made for drainage purposes would in some places have introduced a capriciousness in the way the original Bendelow layout punished shots. For instance, according to penal theory’s understanding of proper punishments, a drive should clear a ditch 80 to 100 yards from the tee (deserving to be in the ditch if it did not), but a perfect 200-yard drive should not be punished by finding a ditch 200 yards from the tee. After the drainage work, however, ditches would have been introduced where they had not been when Bendelow designed his version of the course. Good shots would have rolled into ditches that were never intended to roll into ditches.

On certain holes at Apawamis, therefore, it would have been necessary to reconfigure distances and lines of play to ensure that ditch hazards were located in the appropriate places on fairways and at the appropriate distances from tees and greens.

Figure 14 W.G. Van Tassel Sutphen (1861-1945), circa 1900.

When he reviewed the redesigned Apawamis golf course in the fall of 1900, W.G. Van Tassel Sutphen, editor of Golf (New York), found that the new course had achieved the objective of correctly punishing misplayed shots: “in this country of kopjes [that is, mounds or hillocks] and sluits [a gully or dry ditch], … the punishment is made to fit the crime with unfailing regularity” (Golf, vol 7 no 4 [October 1900], p. 242).

He implicitly awards kudos to Davis for routing holes across and through mounds, on the one hand, and across and alongside ditches, on the other hand, so that players who ended up in these areas got what they deserved as punishment for the bad shot that put them there.

Golf course designs that meted out punishments rationally rather than randomly were regarded as “scientific,” to use the contemporary term.

And so, Sutphen observed about the 14th hole what he thought was true of the course in general: “the course is wide, the lies are good, and the hazards come at the proper distances for first-class play” (p. 247).

Figure 15 Walter J. Travis. Spalding Official Golf Guide 1899, p. 56.

Sutphen understood the relationship between distances and “firstclass play” as US Amateur Champion and golf course architect Walter J. Travis did in 1901:

We will assume that we can drive from 175 to 210 yards; brassey, 170 to 190 yards; get from 150 to 180 yards with cleek or driving-mashie; 120 to 150 yards with a mid-iron, and lesser distances with a mashie.

There is nothing extravagant in these distances with class players.

(Golf, vol no 5 [May 1901], p. 355).

And at Apawamis, the work of Davis in matching hazards to the distances that first-class players hit the ball was not just a matter of adjusting the length of holes to new ditches; as Sutphen observes, Davis also eliminated a ditch that had been regarded as unfair since Bendelow laid out the original course: on “No. 1, the walled ditch that used to unfairly trap a well-hit ball has been covered over” (Golf, vol 7 no 4 [October 1900], p. 243).

Both Davis and Sutphen, that is, regarded the original ditch on the 1st hole as irrational and unscientific.

Acquiring Davis

Apawamis seems to have specifically targeted Davis as the man “to aid them in securing a championship stretch of country,” and probably approached him through its “effective” Golf Committee chairman in 1899, Maturin Ballou – the reigning club champion, and the player who would one year later partner Willie Davis in a best-ball match against Harry Vardon at Apawamis in November of 1900.

Davis was well-known in the United States as the first person to have earned a living in North America as a golf professional: that is, by instruction, club making, greenkeeping, and laying out courses.

Figure 16 Willie Davis in Montreal, circa 1890. The Golfer, vol 2 no 2 (December 1895), p. 51.

Born in Hoylake, Cheshire, England, in the fall of 1861, Davis was taught to play golf in the early 1870s by Young Tom Morris and Davie Strath, for each of whom he caddied when they visited Royal Liverpool Golf Club to play in professional competitions. Davis then apprenticed at Royal Liverpool from late 1876 or early 1877 to the spring of 1881 under Young Tom’s first-cousin John (“Jack”) Morris. During this period, he instructed young Harold Hilton, who would win the 1911 US Amateur Championship on the Davis-redesigned course at Apawamis.

Davis was hired by the Montreal Golf Club in 1881 and spent the next 12 years in Montreal. He served as the club’s golf professional in 1881 and from 1889 to 1892, earning a living as a club maker and ball maker in the interim.

As we know, during his last two years in Montreal, he began to lay out golf courses. In 1891, he was borrowed from Royal Montreal by golf enthusiasts in Ottawa and (perhaps) Kingston (Ontario, Canada) and Shinnecock Hills (Southampton, New York) to lay out the golf courses at these sites.

In 1892, he provided a surrogate designer for the first nine-hole layout of the Tuxedo Golf Club (for which he had supplied clubs and balls in 1889) and at the end of the year he travelled personally to Newport to choose a site for a golf course he would build there when hired as the Newport Golf Club’s professional at the beginning of 1893. When the Newport Golf Club moved to a new site in 1894, Davis laid out a new nine-hole course (as well as a six-hole beginners’ course), and then added another nine holes in 1897. In fact, up to 1899 (when he left), Davis “aided materially in the many improvements and extensions … made at the links of the Newport Golf Club” (Boston Evening Transcript, 23 September 1899, p. 24). And, as we know, he also designed or redesigned other golf courses in Rhode Island, Maryland, Massachusetts, New York, Vermont, and Virginia.