Early Golf in Picton:

Of Presbyters & Proselytes,

1897 - 1907

Preface

Today’s Picton Golf and Country Club was incorporated in 1968. It replaced the Picton Golf Club that was incorporated in 1907. The membership of the Picton Golf and Country Club in 1968, however, was continuous with the membership of the Picton Golf Club of the year before. And so today’s golf club regards itself as having been founded in 1907.

Yet, as we shall see, there was also a Picton Golf Club founded in 1902, and its membership was continuous with the membership of the Picton Golf Club incorporated in 1907.

And there was a Picton Golf Club founded in 1897.

So there is a history of golf in Picton before 1907, and it needs to be told.

In 1980, Fred Rose hinted at part of this story in an article in the Picton Gazette, in which he outlined a process that extended over seven years, involving several elements and stages – introduction to the game, incorporation of a club, and acquisition of land:

The game of golf was introduced to Picton and Prince Edward County in the years 1903 to 1907. The charter for the Picton Golf Club Ltd. was issued in 1907. This club was reincorporated in 1968 as Picton Golf and Country Club.

The land to establish the golf course was obtained … in 1907 with final registry taking place Oct. 1910. (Picton Gazette, 1980)

So Rose alludes to golf developments in Picton as early as 1903. What did he have in mind?

In 1930, as we shall see, the Picton Gazette suggested an even earlier introduction of golf to Picton: sometime in the 1890s.

It seems that we must investigate events at least a decade before the present club’s first incorporation to understand the earliest days of golf’s history in Picton.

Golf Club versus Golf Course

Rose implicitly acknowledges that in discussion of the origins of a golf club, one must bear in mind the distinction between a golf club and a golf course.

A golf course is a piece of land, a geographical location fixed on the earth. A golf course does not change its location: course and location are identical.

A golf club, however, is an organization of people – whether as a legal entity or as a less formal grouping – and so a golf club can change its geographical location without becoming a different club. Golf clubs often move from one piece of land where golf is played to another, as conditions may require or suggest. In Scotland today, for instance, some of the oldest golf clubs in history find themselves playing not just on land remote from where the club began to play, but also on land developed for golf hundreds of years after the club was formed.

And so a golf club may be the same age as the golf course upon which it plays golf, or it may be older or younger than the golf course on which it happens to play the game at any particular time.

The Picton Golf Club has been located on several different golf courses over the years, so of course one must beware confusing the physical duration of one of its golf courses with the club’s own duration as a golf club. The physical duration of particular tees, fairways, and greens in a specific location is less relevant to the history of a club than its duration as a fellowship of people sharing the common cause of developing and promoting the royal and ancient game of golf.

The Royal Ottawa Golf Club makes this point on its website. It was not legally incorporated until ten years after its founding as a golf club. Similarly, the Royal Montreal Golf Club was not incorporated until seventeen years after its founding in 1874. And like both Royal Montreal and Picton, the Ottawa Golf Club had played at different locations before its incorporation:

The Royal Ottawa is one of the oldest golf clubs outside of Britain. It was founded in the spring of 1891, in the dying years of Queen Victoria’s reign, by a group of businessmen and professionals who decided they should organize themselves “for promotion of this healthy and satisfying game” …. The first nine-hole course was on 50 acres of land lent to the club by … a real-estate developer, in Sandy Hill, on the banks of the Rideau …. As Sandy Hill became a more fashionable place to live and property values increased, the club found a new site in Quebec, a mile north of Hull, along the old Chelsea Road. For $15 a year they leased 108 acres of farmland …. In 1901, in order to buy the house and land from the owners, the club became legally incorporated. (Royal Ottawa Golf Club website)

Royal Ottawa incorporated only to enable the purchase of its own land for a golf course.

It turns out that the Picton Golf Club did the same thing in 1907: it incorporated in order to buy land. Yet it had existed as an unincorporated golf club for several years before that, complete with an executive committee comprising a president, vice-president, secretary, treasurer, and members without portfolio.

Many people were part of the story of the pre-1907 Picton Golf Club, and they each had a story of their own.

The Epic Fail of Forgetting D.G. Macphail

In its “centennial number” published on December 29th, 1930, the Picton Gazette explains the origins of golf in the town of Picton: “Golfing was introduced into Picton over thirty years ago by Rev. D.G. Macphail, who was at that time minister of St. Andrew’s [Presbyterian] Church here” (Picton Gazette, 29 December 1930, cited in Canadian Golfer, vol 12 no 9 [January 1931], p. 693).

Written in 1930, the newspaper’s phrase “over thirty years ago” clearly refers to the 1890s, which was the Picton decade in the eventful life of Reverend Donald George Macphail.

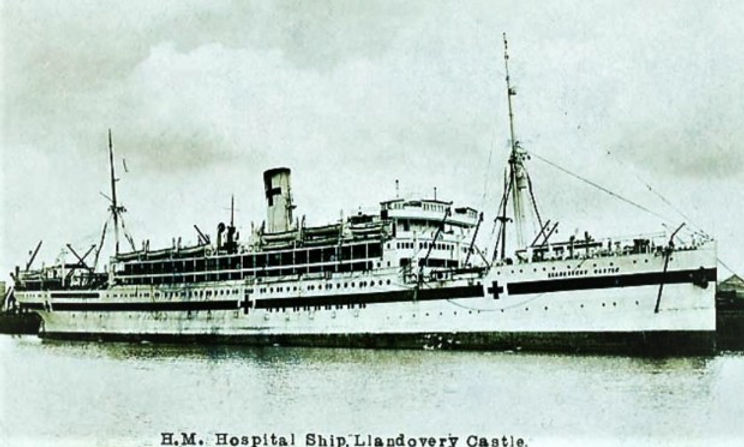

Figure 1 Donald George Macphail, 1889, aged 25, Queen’s Review (October 1929), p. 236.

Macphail (often also spelled Mcphail, and sometimes spelled either way with a capital “P”), was born on a farm near Perth, Ontario, in 1864.

Attending the public schools of that town, he was a very good student, but it was once a week at Sunday School that he was an intellectual superstar, taking to heart Francis Wayland’s The Elements of Moral Science (1835), a careful, accessible explanation of “Theoretical Ethics” and “Practical Ethics” as understood and expressed via a Christian conscience.

Years later, Macphail delivered a speech to fellow Presbyterians in which he implied that the kind of Sunday School stimulation of personal growth that he had enjoyed at Perth could help to build the nation as a whole if it were made available to all: “If Canada is to become a great nation it must produce great men …. Now the Sunday School should be a producer to supply this need” (Jarvis Record, 12 October 1910, p. 1).

Graduating from Perth Collegiate in the late 1880s, Macphail had already determined that he would become a Presbyterian minister. He therefore enrolled at Queen’s University, which was affiliated with the Presbyterian Church in those days.

Macphail studied in the Faculty of Arts, perhaps following a literary inclination instilled by his mother, who was “a remarkably well-read woman in the literary traditions and not afraid to address any question of her day” (Malcolm McGillivray, The Presbyterian and Westminster [1 August 1918]). He easily earned his B.A., even though devoting much of his time in his final year to editing the Queen’s Journal. Upon graduation he immediately enrolled in Theology at Queen’s, combining study in Kingston with study at Knox College in Toronto.

His first posting as a minister was to St. Andrew’s Presbyterian Church in Picton in May of 1892. Once installed at the church, according to the Picton Gazette, the new minister Macphail proselytized not just on behalf of the Christian faith, but also on behalf of the royal and ancient game of golf: “He interested some of the young men of the town and they used to do some golfing wherever a bit of suitable open ground could be found” (cited in Canadian Golfer, vol 12 no 9 [January 1931], p. 693).

The ground where they did “some golfing” seems to have been within sight of people travelling about Picton and so news of the arrival of an ancient Scottish game in town began to spread, and golf attracted the attention of the curious.

It is not clear where Macphail himself was first introduced to golf. Although the game had been played at Montreal since 1873, and the first version of the Kingston Golf Club had been established in 1884, golf did not come to Macphail’s home town until around 1890:

In the 1890s Capt. Roderick Matheson, manager of a local bank, was transferred to Montreal and while in Montreal was introduced to the game of golf at the Royal Montreal Golf Club. Upon his return to Perth, Capt. Matheson decided that his friends might enjoy this new form of recreation, so he invited them to come up to his farm on the banks of the Tay River to try their hand at the game…. The pioneer golfers who accompanied Capt. Matheson were as follows: Charles Stone, T.A. Code, John Code, Judge Scott, W.P. McEwen and Senator MacLaren. From these seven men the Links O’Tay was born. (Perth Courier, 1960).

Macphail had left Perth before Matheson laid out a three-hole course on his farm (which is still the site of the present golf course in Perth, into which the original holes have been incorporated). Yet he certainly returned to town regularly during the 1890s to visit his parents, particularly after his marriage in 1894 and the birth of two daughters, the first in 1895 and the second in 1897, so it is possible that he was introduced to the game at Perth in the 1890s and then brought the game to Picton.

Figure 2 Professor James Cappon, 30 September 1898, Official Golf Guide 1899, p. 312.

Before golf came to Perth, however, Macphail may have been introduced to the game at the Kingston Golf Club.

An early member of that club was Queen’s University’s first Professor of English, James Cappon, who arrived at Kingston in 1888.

Cappon was a Scot who had studied at the University of Glasgow, graduating in 1879 and beginning his career in Europe as a teacher of history. When he was hired by Queen’s University to develop its first Department of English Literature, he brought his love of golf with him to Canada.

As soon as he arrived in the “Limestone City,” he immediately joined the new Kingston Golf Club. He served for decades on its executive committee. He represented the club in inter-club matches, and he represented Ontario in interprovincial matches against Quebec as early as 1892.

In the course of studying for his degree in Arts, Macphail would have taken courses from Cappon and may have learned of the game from conversations with him. Classes were quite small in those days, and Macphail would have had many opportunities for informal conversations with his instructor. The Kingston Golf Club, furthermore, made memberships available to Queen’s University students at favorable rates.

"Suitable Open Ground"

The space needed for golf in the 1890s was not the same as the space that is required today.

On the one hand, an amateur golfer like Macphail and the novice golfers of Picton that he introduced to the game would not have been able to drive the golf ball of the 1890s much more than 200-225 yards, even with a perfect hit. At that time, a hole of 200-225 yards was regarded as a proper “four-shotter,” so Picton’s first golfers could have laid out a primitive three-hole golf course in a field a couple of hundred yards long, and perhaps half as many yards wide.

When Macphail first brought golf to Picton, the ball in use was the gutta-percha ball, or guttie (made from the rubbery sap of a Malaysian tree). In one of the first books on golf ever published in North America, Golf (1898), Gardener G. Smith explained to people who were new to the game that “The ball used in playing golf is made in various sizes, but that most in use measures about 1 ¾ inches in diameter. It is usually made of well-seasoned gutta-percha, grooved or notched on the surface and painted white” (New York: Frederick A Stokes Co, 1908, pp. 11-12.). Note that the rubber had to be “seasoned”: a golfer who ordered a new line of golf balls would have to factor six months of seasoning time into the expected delivery date. Golfers would also buy cans of white and red golf-ball paints, since the gutta-percha rubber would not retain its original paint, and so balls would begin to return to their natural black colour after several rounds of golf began to wear off the paint.

As at Perth around 1890, so at other places in Canada like Brantford and Nova Scotia in the 1870s, a rudimentary three-hole course that was laid out on a commons or in a farmer’s field sufficed to get golf underway. Only a small number of people in these communities knew of the game – Roderick Matheson was the only one in Perth, and that was because he had gone to Montreal! – and an even smaller number of people possessed golf clubs.

Macphail and his small cohort of golf proselytes could easily have laid out a makeshift course within the open area inside the racecourse at the Crystal Place fair grounds. Compare below the 1919 aerial view of the Picton fair grounds with a contemporary aerial view of the racetrack within which the ancient Musselburgh Links (near Edinburgh, Scotland) are laid out (this nine-hole golf course hosted the Open Championship four times in the 1800s).

Figure 3 1919 aerial photograph of Picton (left) and a contemporary view of the Musselborough Links, Scotland.

In Musselburgh, seven golf holes – in whole, or in part – are laid out within the infield of the racetrack.

If Macphail and his fellow devotees of the royal and ancient game ever used the fair grounds for “some golfing,” they did not use it regularly, for the Gazette refers to their doing “some golfing wherever a bit of suitable open ground could be found,” which implies that their golf grounds never became associated with any one location.

A slightly earlier photograph of the same fair grounds from the opposite direction shows that the racetrack area was surrounded to the north, east, and west by open fields. People could have played golf in these fields.

Figure 4 View northward beyond the Crystal Palace fair grounds circa 1912. Picton: the Scenic Town of Canada, the Angler’s Paradise Home (1912), p. 18.

Any pastureland grazed by cattle or sheep, or even horses, would have sufficed to allow Macphail to drive several stakes into the ground a couple of hundred yards apart, and then drive balls toward each in succession as a circuit of golf holes.

That was how golf was introduced to hundreds of communities in North America from the 1870s to the 1890s.

Other Golf in the Neighbourhood

Macphail may have observed how the game was being played in the mid-1890s on Le Nid Point on the Bay of Quinte across from the Glen Island resort, which was frequented by Pictonians at that time. Each summer from the mid-1890s onward, a provisional golf course was laid out at a place called Camp Le Nid. In the open fields to the east of the Camp Le Nid tents, play on this golf course was clearly visible across the open water on all sides of the point.

Figure 5 1954 aerial photograph of Le Nid Point in the Bay of Quinte between Perch Cove and Bass Cove.

In 1886, Walter S. Herrington, of Napanee, had led a band of fellow Victoria College law graduates to a camping site on Le Nid point belonging to a farmer named Ruttan, whose United Empire Loyalist ancestor Peter Ruttan had arrived there in the 1780s. Camp Le Nid was the site of summer vacations by Herrington’s widening band of colleagues and friends from 1886 to 1946 (the year before Herrington died). The annual vacations at Camp Le Nid were to allow Herrington’s fellow graduates across Canada and the United States (and one other who came from South Africa!) to rough it in the bush, living in tents, and learning to know each other “as we are,” as Herrington later wrote (Reveries of Camp Le Nid, 1908). The campers’ motto was “Sans souci, sans cérémonie, sans peur, et sans reproche”: without worry, without ceremony, without fear, and without reproach (Dominion Illustrated, Vol vii no 168 [19 September 1891], p. 267).

We find the first reference to golf at the camp in Herrington’s account in the Napanee Express of 1897 of the opening of the camp that summer. He describes club members arriving from Baltimore, Montreal, Toronto, Ottawa, and Oshawa and then departing “per steam yacht Jessie Forward” for Ruttan’s Point: “After a pleasant sail down the river and bay we arrived at Ruttan’s Point at 5 p.m. and before dark had our tents pitched and our baggage under shelter”; the baggage included golf clubs: “The Golf links, as usual, are the main source of attraction for the sporting members of camp” (30 July 1897).

For golf to have become “usual” at the camp by 1897, we can infer that it had been played there since the mid-1890s.

Figure 6 Herrington (standing), with two unidentified golfing companions, at Camp Le Nid in the late 1890s. Photograph N10992 Courtesy of Lennox and Addington County Museum and Archives.

The earliest photographs of the golf course at Camp Le Nid show that it was quite primitive. The first photograph below was taken on one of the “Visitors Days” at the camp (when the exclusively male camp members entertained women and children for a day). A woman poses with a golf club in hand as though she is about to tee off. Note in each of the two photographs below the flags stuck in the ground as tee markers.

Figure 7 First tee at golf links of Camp Le Nid late 1890s. Photograph N-02720 courtesy of Lennox and Addington County Museum and Archives.

Figure 8 Another teeing ground on the golf links of Camp Le Nid late 1890s. Photograph N-11016courtesy of Lennox and Addington County Museum and Archives.

Simple poles of some sort, not flagsticks, marked the location of golf holes in the 1890s, as seen below.

Figure 9 Camp Le Nid putting green late 1890s. Photograph N-02691 courtesy of Lennox and Addington county Museum and Archives.

Figure 10 Seven men gathered around a putting green at Camp Le Nid late 1890s. Photograph N-11070 courtesy of Lennox and Addington County Museum and archives.

The putting green in the photographs above is about three feet in diameter. Its grass is trimmed shorter than that of the fair green (today called the fairway). The hole at the centre of the putting green is marked by a pole about two feet in height, to which is fixed a rectangular piece of wood, measuring about four inches by ten inches.

Golf holes being very short on rudimentary courses of this sort, Herrington and his golf-mad band of Le Nid campers somehow routed a 14-hole golf course through the fields that Ruttan allowed them to use. We learn of this 14-hole layout from a second story in the Napanee Express about the 1897 season at the camp: “The golf championship rests between Mr. Herrington, of Napanee, and His Honor Judge Ingram of Baltimore, each having covered the links (14 holes) in 67 strokes” (13 August 1897). The newspaper also notes that “Several excellent photographs of camp life have been secured this year. These will be bound in albums and preserved by the members as souvenirs of the summer’s outing” (13 August 1897). We might suspect that the photographs of the golf course above were among these photographs “secured” in 1897, and so might speculate that the photograph of the seven men above documents the climax of the club championship that summer.

The men of Camp Le Nid that we see in the photographs above were very aware of nearby Glen Island, which was developed extensively as a resort during Macphail’s time in Picton.

According to an article by Jane Lovell in The Neighbourhood Messenger, Glen Island was originally known as Hog Island in the 1880s and a hotel of some sort was built on it at that time, but in 1890 it was “bought by the Dingman brothers of Picton and the resort was renamed Glen Island” (Jane Lovell, “Vacation Destination: The Bay of Quinte,” The Neighbourhood Messenger, June 2013, p. 10).

The island stayed in the Dingman family for the next 32 years and during that period the resort flourished. While there was never a hotel, as such …, there were up to 29 cabins and cottages. In 1892, furnished and unfurnished cottages could be had from $3 to $5 per week …. The …. resort may have been able to accommodate 150 people in the cabins, in the area partitioned for sleeping quarters above the dance hall, and in the “tent camp” erected yearly at the far eastern end of the island. Mail and newspapers were delivered daily by steamer from Picton and Kingston, and by 1900 a summer post office had been established on the island. Rail and steamer timetables were coordinated to allow convenient travel to and from the resort from Toronto and Rochester, and from a wider net of American cities, including Buffalo, Philadelphia, Niagara Falls, Baltimore and Pittsburgh. Croquette, quoits, lawn bowling and tennis vied with fishing trips and soirées at the dance pavilion as amusements for the resort guests. (Lovell, pp. 10-11)

Figure 11 Glen Island ferry wharf circa 1900. Lovell, p. 11, indicating the photograph courtesy of Harry Wells.

The men from Camp Le Nid regularly visited Glen Island:

The many attractions of Glen Island held an irresistible draw for the men who annually attended a “gentlemen’s camp” across Bass Cove on Ruttan’s Point, just to the north of the Island…. Initially, the camp was a very rough affair consisting of a few canvas tents erected on an acre or so of land leased from the local farmer. Over the years, however, more commodious structures were erected, including a kitchen and dining hall in 1897, and an icehouse soon thereafter. It was during this period that Glen Island’s dining hall and dance pavilion, as well as the potential for congenial social interaction on the island, enticed the campers from Le Nid to make the crossing from the camp to the island by boat. (Lovell, p. 12)

I note that it “was a popular destination for excursions by steamer out of Napanee, Deseronto and Picton” and that “The most numerous were Sunday school excursions and picnics” (Lovell, p. 11). And so I wonder if Reverend Macphail, Picton’s great promoter of Sunday School as a foundation for the formation of Canada’s future leaders, arranged these sorts of outings to Glen Island for his congregation.

Whether or not Macphail visited Glen Island either in connection with outings by his church, or perhaps as a vacationer, it is certain that Macphail enjoyed fishing in this area. Even after he had been transferred to other churches in Alberta and Ontario, Macphail returned to the area to fish. And of course the golfers at Camp Le Nid were quite visible from the water.

One way or another, it seems inevitable that Macphail would have learned of the like-minded men in the Bay area who were also doing “some golfing.” Given the passion for golf shown by Macphail’s pioneering efforts in Picton on behalf of the game, one wonders if he contrived an opportunity to talk with the men of Camp Le Nid about their golf course, or perhaps an opportunity to play a round of golf with them.

The 1897 Golf Club

There is evidence from Napanee that by 1897 Macphail had produced a critical momentum in the development of the game of golf in Picton:

Figure 12 Napanee Express, 8 October 1897, p. 1.

By the end of the summer in 1897, there was clearly a large enough group of people in Picton playing the game for the desire to form a club to have arisen. Perhaps the local devotees of the game formed this club in order to organize formal competitions amongst themselves. Perhaps they wished to pool their resources by means of membership fees to finance the rental of a pastureland where they could set up a permanent golf course.

At this point, all we know is that the first Picton golf club was formed by the fall of 1897.

"Several Pictonians" Proselytized

The sight of Macphail and his band of “young men of the town” trekking across Picton to their various makeshift golf courses had piqued the curiosity of an older generation of Pictonians. The Picton Gazette observes – with regard to Macphail’s popularizing of the game with some of the young men of the town – that “It was about this same period that several Pictonians became interested” (cited in Canadian Golfer, vol 12 no 9 [January 1931], p. 693).

In those days, when the device known as a golf club appeared in Canadian towns, most people had never seen one before, so they were invariably interested to learn what this odd tool was for and how it was used.

James E. Darling, an employee of the Bank of British North America who introduced golf first to Brantford and then to Halifax in the 1870s, spoke of the reaction of people in those days to the site of golf clubs. On his way from Brantford to Halifax in 1873, Darling found that his golf clubs made him a curious figure: “I remember, going down the St. Lawrence on my way to Halifax, the many inquiries as to what my clubs were for. We had to change to a small steamer to run the rapids, and, having no cabin for this part of the trip, I was carrying my clubs in my hands. The boat was full of American tourists, and the strange clubs, especially the irons, seemed to excite their curiosity” (Canadian Golfer [July 1915], vol 1 no 3, p. 189).

And of the site of a golf course itself was equally exotic and mysterious, as we can see from an account in the Orillia Packet of the way community members misinterpreted what a sequence of flags appearing across a farmer’s field meant:

The report that the C.P.R. was surveying a line into Orillia had a rather amusing origin. Some who saw the men placing the flags in laying out the golf links on the Dallas farm at once jumped to the conclusion that it was a C.P.R. survey party running a line, and immediately brought the good news to town. (cited in the Barrie Examiner, 5 May 1898, p. 8)

Darling’s account of reactions to his travelling across Canada with golf clubs in his hands and the amusing item in the Orillia Packet allow us to imagine the response of Picton residents in the 1890s to the site of Macphail and his golf converts strolling through the town centre with golf clubs in hand on the way to the open ground where they would play golf on a field with flags arranged across it.

The “several Pictonians” who also “became interested” in golf at this time were probably no different from fellow Pictonians generally in gossiping about Macphail’s obsession with this ancient Scottish game, and they were probably no different from others in watching intently as Macphail and his converts swung the strange hickory sticks with a never-before-seen motion. The difference was that these “several Pictonians” probably asked to be allowed to handle a club and ball, and then to take a swing with a club at a ball.

And then the die was cast.

Like many people before and since, those who hit a pure shot, long and straight, experienced the usual epiphany: I must do that again!

Pictonians Who Count

Although the Picton Gazette says in 1930 that all these things happened “about [the] same period” “over thirty years ago,” the order of events seems pretty clear: first, Macphail came to town and played golf; second, he thereby inspired some of the young men of the town to take up the game; third, Macphail and the young men in turn inspired “several Pictonians” to become interested in the game.

The newspaper’s narrative of these events implies that it was the “several Pictonians” who “became interested” in the game (in addition to Macphail’s “young men of the town”) who were the most important converts to golf.

Oddly, these men are named “Pictonians,” whereas Macphail and his young golfing cohort are not. Macphail and the “young men of the town” are implicitly distinct from these other men. One presumes that the “Pictonians” in question were older and of greater standing in the community than the “young men of the town”: these were the men who counted when it came to whether or not the game of golf would have a future in the town.

By the ambiguous conjunction “and,” the newspaper’s sentence links these Pictonians’ interest in the game and the laying out of Picton’s first permanent golf course: “It was about this same period that several Pictonians became interested and a course was laid out just outside the town limits” (cited in Canadian Golfer, vol 12 no 9 [January 1931], p. 693). It is not clear whether the “and” marks two events that simply happened to occur around the same time, or whether it marks two events related as cause and effect.

Whatever the case may be with regard to the missing explanation of any relationship between these two events, there is something else missing from this part of the newspaper’s account of the introduction of golf to Picton, and that concerns the necessary stage between the interest in the game taken by “several Pictonians,” on the one hand, and the laying out of the first permanent golf course, on the other.

We miss an account of the formation of the golf club that must have arranged for the use of the land where the course would be laid out.

Was it the golf club formed at the end of 1897?

Or had a different club been formed since then?

The Picton Golf Club of 1902

As we shall see in another section below, the Daily British Whig published items in March of 1903 and March of 1904 that named the people elected each year to the executive committee of “the Picton Golf Club” (28 March 1903, p. 4; 31 March 1904, p. 2).

Similarly, in March of 1903, the Toronto Globe referred to the election of officers “at the annual meeting of the Picton Golf Club,” so it would seem that the Club had been formed prior to 1903 (27 March 1903, p. 10). Otherwise, the Globe would have referred to the first meeting of the Picton Golf Club.

But how long the club had existed before 1903 was not exactly clear. Later in the spring of 1904, however, in a general item about events in Picton, we read in the Daily British Whig that “The golf club is in its third year” (27 May 1904, p. 6).

We know, then, that the Picton Golf Club was formed in 1902.

Confirmation of this fact comes from Cleveland, Ohio, in the summer of 1922. That is when a man named Arthur Field wrote to the Cleveland Sunday News-Leader to tell readers about the Picton Golf Club: “Picton is a beauty spot in the Bay of Quinte district, and the nine-hole course overlooks the bay. It is one of the best kept courses we’ve seen for many a day” (Arthur Field, Sunday News-Leader [Cleveland, Ohio], July 1922, cited in Canadian Golfer, vol 8 no 4 (August 1922), p. 364). He tells of “the influx of the numerous American visitors who have recently invaded Glen Island, an ideal camping place,” and suggests that because of the increased play on the course caused by this influx “there is some talk amongst the moguls behind the game of enlarging the course” (Field p. 364). He then describes two of the club members he has met (both were directors of the club in those days): Colin Hepburn, “who has the best private putting green that one will find in many a day’s travel,” and H.B. Bristol, “another great enthusiast” (Field, p. 364). It seems to have been from these “moguls behind the game” that he learned the following: “The Picton Golf and Country Club [sic] was first established in 1902 and incorporated in 1907” (Field p. 364).

The First Executive Committee

The relationship between the golf club formed at Picton in 1897 and the “Picton Golf Club” formed in 1902 is not clear.

After the 1897 reference to the former in the Napanee Express, the next reference to a golf club in Picton that I can find in a local newspaper comes in March of 1903 in the Daily British Whig: “The Picton Golf Club has organized with these officers ….” (28 March 1903, p. 4).

As we know, this statement does not mean that the club was organized for the first time in March of 1903. In fact, it means almost the opposite, for this locution was the way newspapers of the day indicated that a pre-existing club like Picton’s had organized for the coming season by electing the officers in question.

We shall meet in sections below the officers elected to the executive committees of 1903 and 1904. Unfortunately, however, I can find no newspaper references to the executive committee of 1902.

It is interesting to note, however, that only one person left the executive committee between 1903 and 1904. Every other member of the 1903 committee continued to serve on the 1904 committee. We might presume, then, that the constant figures on the committees of 1903 and 1904 were also the founding committee members of 1902.

Before meeting these committee members, however, let us review a few of the decisions made anonymously by the first executive committee.

Location! Location! Location!

One of the most important actions of the 1902 executive committee was to arrange for the laying out of a permanent golf course.

New golf clubs invariably organized in the late winter or early spring – when a sportsman’s fancy turns to golf. A meeting of interested persons was called, a committee was appointed, and a top priority was to arrange for the use of land as a golf course.

The Picton Gazette concludes its 1930 account of the introduction of golf to Picton by observing that “It was about this same period that … a course was laid out just outside the town limits along the Cherry Valley road” (cited in Canadian Golfer, vol 12 no 9 [January 1931], p. 693).

Fred Rose explains that the first golf course was laid out “on the north side of Lake Street, near Sandyhook” (Picton Gazette, 1980). This land can be seen from an oblique angle in the annotated aerial photograph shown below that was taken in the 1940s.

Figure 13 Detail of an aerial photograph of the Picton air base taken in the 1940s.

Land Ownership

Did the golf club own the land on which this first permanent golf course was laid out?

Was this land north of East Lake Road regarded as a commons?

We can see on an 1878 map of Hallowell Township that part of the land in question was marked out even then for residential development. We can see below that rectangular lots on the north and south sides of what would be named Upper Lake Street were marked precisely on the map (appearing just below the center of the map under the name “D. Platt.”)

Figure 14 Detail from Hastings and Prince Edward Counties 1878 (H.Beldon & Co., 1878).

After the golf course was laid out on this land, it continued to be used by other groups. We read in the fall of 1904, for instance, that “The young ladies’ walking club had their tramp to the golf links this week” (Daily British Whig, 11 November 1904, p. 4).

The Picton Gazette writes ambiguously about this property on which the Picton Golf Club’s first permanent golf course was located: “Later this property was sold and the present links purchased” (cited in in Canadian Golfer, vol 12 no 9 [January 1931], p. 693).

The passive construction of the sentence makes it impossible to determine whether it means “Later this property was sold” by the Picton Golf Club, or “Later this property was sold” by the person who had allowed the Picton Golf Club to use it.

As the club had not yet been incorporated, however, it seems more likely that the land where its first golf course was laid out had been either loaned or leased to the club, as was the case for the Ottawa Golf Club in the 1890s before it incorporated in 1901.

Laying Out the First Golf Course

Whether or not the new Picton golf Club hired a golf professional to lay out its first golf course is not clear. In 1902, the pickings were slim: there was a golf professional at Royal Montreal, another at the Ottawa Golf Club, and a third at the Toronto Golf Club.

Note that to lay out a golf course around 1900 did not take long, and it could be accomplished with local resources.

No earth was moved during the building of such a course, either to shape a fairway or to build up a green. A farmer’s pastureland was generally chosen for a golf course because the land had been cleared and had well-established pasture grass growing on it – grass that only needed to be cut regularly in order to produce a decent fairway surface from which to play a golf shot.

Putting greens were developed on a level area of the field. Rakes and shovels might be used to fill in minor depressions or to shave off little rises in order to produce a flat surface. The preference in those days was not for an undulating or wavy surface, but rather for a fairly level surface that would minimize the break of putts made across it.

The green comprised grass cut shorter than the fairway grass, and it was usually cut in the shape of a square, with sides of perhaps 20 to 30 feet.

The putting green would be compacted to produce a relatively smooth putting surface on which the bounce of a rolling ball would be minimized. With a minimum of manpower, the compacting would be achieved in one of three ways:

(1) by rolling the entire putting surface with a heavy barrel-shaped cylinder on a horizontal axis attached to a handle (designed to be pulled by two men);

(2) by thoroughly soaking the putting surface with water, then placing planks over it, and finally pounding the planks with a heavy object;

(3) or simply by pounding every square foot of the putting surface with a heavy-handled instrument with a flat square bottom, as in the photograph below.

Figure 15 A late nineteenth-century golf groundsman (greenkeeper) flattens the surface of a tee or green by pounding it. Michael J. Hurdzan, Golf Greens: History, Design, and Construction [Wiley, 2004], chapter 1).

In the early 1900s, the construction of a golf course by these methods could be completed in several weeks from start to finish. Play on the course would then commence immediately.

And as for the routing of the golf holes?

Practical advice on building a golf course was scant at the turn of the century. James Dwight’s section on “Laying Out Links” in his 1895 book Golf: A Handbook for Beginners comprised just seven sentences: “It should be understood that links vary greatly in length as well as in the character of the ground. There is no definite distance between the holes. If you possibly can, get some competent person to lay out the course for you. It is hardly likely that a beginner can take all advantage of the different natural hazards, etc. The distance between the holes must vary according as open places occur with some hazard in front. As to distance, an average of 300 yards makes a good long course. Some of the holes should be 400 to 450 yards apart, and one short hole of 100 to 120 yards” (p. 41). That is all the advice he offers. Now build it!

In 1897, the Wright & Ditson sporting company published a Guide to Golf in America, which included a section on how to lay out a golf course that must have seemed encyclopedic compared to Dwight’s book. I provide here a summary of the sections “Laying Out a Course” and “Construction and Upkeep”:

Laying Out a Course

The game may … be played on any fields affording requisite room and turf that can be kept in condition to afford reasonably good lies between the holes…. It is not possible or desirable that the distances between the teeing-grounds and holes should everywhere be the same…. Holes should not be too much alike .… The distances and hazards should be as varied as possible. The putting-greens may be sometimes on the flat turf, sometimes on the top of a ridge or knoll, or even on the side of a gently sloping hill. The first drive from the tee should be sometimes from the crest of a low hill, and sometimes on the flat; and the hazard to be surpassed (for there should be always some hazard or bunker to trap a poorly played drive) should be sometimes near the teeing-ground and sometimes at nearly a full drive’s distance from it….

Selecting a convenient place for the first teeing-ground, not too far from the club house, and having determined from the general “lay of the land” the direction in which the first hole is to be, walk in that direction and seek a convenient stretch of level turf which may be used as the putting-green, at least 250 yards from the tee, for the first hole should not be a short one. See that a full drive will be rewarded with a tolerably good lie. Having placed a stake in the centre of the spot selected for the first green, consider where is the most favorable spot for the next teeing-ground to be placed….

Do not be afraid of hazards. A good sporting hole may be often made in the most unpromising place if a good drive can place the ball where a good lie can be obtained for a second shot….

Where nature, by some oversight, has forgotten to provide hazards or bunkers, they should be built by man. The best are made by building a pile of earth work, about waist high and with sloping sides…. The trench behind the mound should be filled with loose sand, if possible, as … it is less unpleasant to play a ball out of sand than out of the mud that is sure to collect in such a place in wet weather….

Running water and small ponds add to the variety of the course and are desirable hazards.

Returning to the second teeing-ground, we continue as before, weighing considerations of distances, difficulty of ground, favorable spots for putting-greens and position of hazards, and driving our little stake that marks the position of the future putting-greens as we go along, constantly bearing in mind that we must return to a point somewhere near where we started, and arriving at the last hole but one choose our last teeing-ground, so that we may return to the home green in such a way as not to endanger the lives of members who may be watching the game from the clubhouse veranda or grounds, and at the same time not make the hole too easy, for the last hole should be a difficult one.

Now we may go over the whole course again and see if it cannot be improved by shifting this hole or that teeing-ground a little. If it cannot be so improved we may return home and give our orders for the construction of such holes, teeing-grounds and bunkers as we have described.

Construction and Upkeep

It is not necessary or desirable that the greens should be absolutely flat, but … it is essential that they should be as smooth as may be. Wetting and pounding under heavy boards will work wonders, and grass treated in this way takes far less time to become playable than when the whole is re-sodded…. To keep the greens in the best condition, they should be cut and rolled every morning and after every rain. A heavy roller drawn by two men should be used, and the lawn mower should be set low…. The putting-green is defined by the rules as all ground within twenty yards of the hole, not including hazards, but all putting-greens are not kept in that swept and garnished condition we have a right to expect for so great a distance. Indeed, on many links we have to be satisfied if we find tolerable smoothness within five yards of the hole….

The teeing-ground is sometimes indicated by a parallelogram in whitewash marked upon the ground…. This is drawn upon the level ground or on a gentle upward slope, and is the simplest and cheapest form. Sometimes, however, there is not sufficiently large or level space for this, and a teeing-ground has to be built. These are built of earth, well pressed and pounded down and covered with sod….

Through the green, the amount of care required to keep the course as it should be depends altogether on the quality of the soil. Loose, sandy-soiled links practically look out for themselves; but many inland courses on rich, clayey soil require constant attention with a horse mower. In any case, the grass should certainly be short enough anywhere near the middle of the course to afford a good lie to the ball … for few things are more provoking than to find a well-played ball lying so deep in grass that a stroke must be sacrificed to play it out. At the sides and edges of the course longer grass does not matter so much, as it may be considered a fit punishment for erratic play. (pp. 29-35)

Longer Courses for Longer Balls

Incidentally, by 1902, Picton golfers may have been motivated to find a place to play golf that was larger in area than the “open ground” where they had played previously, for a new golf ball had been invented, and its increasing popularity meant that more space for playing golf was required than had ever been needed before.

From 1900 to 1902, the gutta-percha golf ball was gradually replaced by the rubber-wound, rubber-core golf ball invented by a man named Haskell, who patented it in 1899. This ball – called the “Haskell Flyer” – could be driven twenty yards further than the gutta-percha ball.

The latter had not been dimpled, but rather scratched and scored in various ways when golfers discovered that the gutta-percha ball that was roughed up after play (losing its smooth manufactured surface) flew further than it did when new. The scratched golf ball could also be played with better control by the golfer. These discoveries led to the study in the early 1900s of the aerodynamic effects of dimples on a golf ball. When the new rubber-wound, rubber-cored golf ball received scientific dimples, it flew another twenty yards further.

After both the British and US Opens were won in 1902 by players using the new rubber-wound, rubbercore ball, it became the golf ball of choice. The gutta-percha golf ball went the way of the Dodo bird.

Consequently, golf courses began to be lengthened to accommodate the new ball.

Five Holes

Fred Rose points out that the golf course designed in this area was “a five-hole layout” (Picton Gazette, 1980). The executive committee of 1902 may have been confined to a five-hole layout because of constraints relating to the size or nature of the golf course property.

Note, however, that in the 1890s and early 1900s, five-hole layouts were popular all over the world when it came to designing a community’s first golf course. At Saint John, New Brunswick, in the mid1890s, “The original course was a five-hole layout with the longest hole being 200 yards” (https://www.riversidecountryclub.ca/news/a-brief-history-of-the-riverside-country-club). The first planned golf course in Kansas City was a five-hole course built in 1894. Along the shores of Lake Michigan near Chicago in 1896, the exclusive Edgewater Golf Club built a five-hole course. In 1893, the first golf course in Kuala Lumpur was “a makeshift five-hole golf course” (Sun Daily [Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia], 25 April 2017).

And so on, and so on.

Perhaps most importantly, the nearby Napanee Golf Club had a five-hole golf course, which had served the members well since 1897. The golfing communities in the two towns seem to have been close. Recall that the Napanee newspaper had reported the formation of the Picton Golf Club in the fall of 1897. In 1904, a team from the Napanee Golf Club visited the Picton five-hole golf course: “The golf tournament held at the links this afternoon resulted in a victory for Picton against Napanee. The ladies of the club served a delightful supper after the game” (Daily British Whig, 26 May 1904, p. 8). In 1905, a Napanee team again travelled to Picton to contest a match: “The tournament held on the golf links, Wednesday, was in every way a delightful success. Napanee sent a contingent of ten, and they were the victors by two points. The ladies of the club served a delicious supper after the game” (Daily British Whig, 27 May 1905, p. 4).

At a time when a small-town golf club like Picton’s might have between one and two dozen members in total, and seldom (if ever) had its full membership on the course at the same time, five golf holes laid out parallel to each other could easily be played as nine. Because the holes would all be side-by-side, with a green at the end of one hole not far from the tee of another hole, once golfers had finished the fifth hole, they could return to where they had begun by playing their way back in reverse order on the very holes played on the way out: golfers would play the fourth hole as their sixth hole, the third hole as their seventh hole, the second hole as their eighth hole, and the first hole as their ninth hole.

Of course the holes could also have been arranged in a circuit (either clockwise or counter-clockwise) so as to bring golfers back to where they began, or the holes could even have criss-crossed each other, and so on.

Whither Macphail

Of all the advice in the self-help books that might have been relevant to the situation of the new Picton Golf Club, perhaps the most important was offered by Dwight: “If you possibly can, get some competent person to lay out the course for you. It is hardly likely that a beginner can take all advantage of the different natural hazards, etc.”

The Picton Golf Club may have felt that it had just such a competent person ready to hand: Reverend D.G. Macphail.

Note, however, that Macphail left Picton at the end of June in 1902. At his Sunday sermon on March 12th , 1902, Macphail announced to his congregation that he would be leaving Picton for Alberta (Ottawa Citizen, 22 March 1902, p. 1).

There was no obvious church-related reason for making this announcement when he did. He would not be leaving town for three and a half more months and the officials of the Presbyterian Church in Eastern Ontario would not be able even to consider the matter until their regular April meeting a month later, so it is not clear why he decided to make his announcement early in March.

I wonder if the timing of Macphail’s announcement to his congregation was determined by the impending organization of the Picton Golf Club for its inaugural season in 1902.

In 1903 and 1904, the club’s organizational meetings took place in March. The planning to create the new golf club in 1902 may have begun even earlier than March. If, as seems likely, Macphail was invited to participate in the planning of the new club, it is possible that he spoke to church members when he did because the organization of the golf club forced his hand.

Macphail seems to have been the most experienced golfer in Picton. He may well have struck the “several Pictonians” who had become interested in the game as the “competent person” that Dwight said should take charge of laying out a club’s first golf course. I expect that he was asked to stand for election to the executive committee. Macphail knew that because he was planning to leave Picton at the beginning of the summer, he would not be able to serve out a full term on that committee. He would have to explain this matter to his fellow golf enthusiasts. But he would have recognized immediately that members of his congregation, not his fellow golf-club planners, deserved to be the first to hear the news that he was leaving town.

My suspicion is that he agreed to serve as vice-president of the new Picton Golf Club for as long as he was in town.

In any event, Macphail did not leave Picton until the end of June. Whether or not he had an official role on the Picton Golf Club’s executive committee, he was the golfer in town with the most experience, so he is likely to have been consulted about the selection of the East Lake Road land as the site of the club’s first permanent golf course. And he was also probably asked to advise on the routing of golf holes across it.

I expect that he also played golf on the new course.

When Almonte established its first golf club in the spring of 1902, at exactly the same time as Picton did, play was underway on its newly laid-out course by the middle of May. Before Macphail left town, he would have had plenty of time to play quite a few rounds of golf on the new course, and I cannot imagine that he would have passed up the opportunity to do so. He must have been quietly satisfied by the fact that the town’s first permanent golf course had developed organically out of what he had begun in the 1890s.

The Presbyterian Succession

The Presbyterian minister who succeeded Macphail at St. Andrew’s was Walter Wallace McLaren.

Figure 16 Walter Wallace McLaren, circa 1908.

Like Macphail, McLaren was from Eastern Ontario. Born in Renfrew in 1877, he achieved sustained success in the local schools and, like Macphail again, attended Queen’s University, enrolling in the Arts programme in 1894. As an undergraduate he won many prizes and scholarships, including the medal in political science. And once again like Macphail, he served as editor of the Queen’s Journal. McLaren graduated with an M.A. in 1899 and a B.D. in 1902. After half a year at a Presbyterian church in Hamilton, he was called to St. Andrew’s at Picton in the fall of 1902.

He quickly adopted the life of a Pictonian. He served as the minister of Picton’s Sons of Scotland Society (alongside the society’s “senior Guard,” future Picton Golf Club director James de Congalton Hepburn).

He invited to his sermons groups ranging from the Citizens’ Band to the local lodge of the Ancient Order of United Workmen. The congregation loved it: “Rev. W.W. McLaren’s sermon was much enjoyed” (Daily British Whig, 7 June 1904, p. 3).

More importantly, just as Macphail had brought a love of golf with him to Picton, so did McLaren. As soon as he arrived in town, he not only became a member of the Picton Golf Club; he was elected its vice-president. It is almost as though to do so were part of the Presbyterian ministry at Picton!

And perhaps, in a way, it was.

It seems likely that members of the 1902 executive committee carried on in the same roles for at least the first three years of the club’s existence. The person who was president in 1903 was president also in 1904; the same is true of the people who served as vice-president and secretary. The 1903 treasurer left town, so he was replaced by another person in 1904. So as I indicated above, I regard the president, secretary, and treasurer of 1903 as probably the president, secretary, and treasurer of 1902.

Now we know that the vice-president of 1903, W.W. McLaren, was not the vice-president of 1902, for he arrived at St. Andrew’s only in October of 1902, so there was a different vice-president of the Picton Golf Club in 1902.

Was it Macphail? Was his departure for Alberta in the early summer of 1902 the reason that there was a position open on the golf club’s 1903 executive committee for the new Presbyterian minister?

For some reason, newcomer McLaren was slotted right into the vacant executive committee position.

Interesting in this context is the fact that McLaren was about the same age as “the young men of the town” that Macphail had converted to golf in the 1890s. McLaren’s age definitely stands out: at twentysix years of age, he was the youngest member of the 1903 executive committee by thirteen years. He would have been an appropriate representative on the committee of the younger members of the community whom Macphail had converted to golf. And of course there may have been a higher than usual proportion of young Presbyterean churchgoers amongst that group, the ones most likely to have been the first to have been converted by Macphail’s passion for golf.

McLaren’s service at the Picton Golf Club is notable. Although he was a member of the club for just three years, while he was vice-president of the club it established its first ground committee and built its first clubhouse.

When he left Picton in 1905, it is clear that he had also made a notable impact upon St. Andrew’s: “Rev. W.W. McLaren conducted service in the Presbyterian church, Picton, on Sunday. Large congregations assembled as this was his leave-taking, prior to his departure for Harvard” (Daily British Whig, 21 September 1905, p. 6).

He received his Ph.D. from Harvard in 1908 and thereafter pursued an academic career.

He began his teaching career in Tokyo, Japan, being appointed professor of economics and politics at University of Keio, Tokyo, from 1908 to 1914. While there he wrote the Political History of Japan and Present-Day Japanese Government (1914), a work still cited by scholars today. He then joined the staff of Williams College (Williamstown, Massachusetts). He was also appointed economist for Far Eastern countries in the United States Department of State, secretary to the American delegation and chief of the international secretariat at the Washington Conference on Electrical Communications in 1920, executive secretary of the Institute of Politics at Williamstown (which taught government officials from around the world), and chairman of the executive committee of the Conference on Canadian-American Affairs in 1935, which brought him back to Canada frequently in negotiations with Canadian government officials regarding trade relationships between the two countries. He received honorary doctorates from Lawrence College (Wisconsin) and Queen’s University, retired in the late 1940s, and moved to Pasadena, California, where he died in 1970 at 93 years of age.

1903 Executive Committee Members

Nowhere on the Reverend Doctor’s curriculum vitae was it ever mentioned that McLaren was a founding father of the Picton Golf Club.

Yet the Picton Gazette said in 1937 that another person who served alongside vice-president McLaren on the 1903 executive committee as its treasurer, Edward Augustus Bog, “was a co-founder of the county’s first golf club” (Picton Gazette, 1937, cited in Picton Gazette, 20 April 2017, p. 8).

McLaren and Bog were listed along with the other officers in the Daily British Whig in March of 1903:

Figure 17 Daily British Whig, 28 March 1903, p. 4.

Born in Picton in 1858, Bog was a banker. He worked in the Campbellford branch of the Standard Bank from 1883 to 1900, serving most of that time as manager, but he was then transferred to the Picton branch to serve as its manager. But he was also a man on the rise, for he was concurrently serving as the Standard Bank of Canada’s Assistant Inspector.

Bog immediately entered into Picton public life. In 1902, he was named a future public-school trustee (for the 1904 year). He served that year as vice-president of the Picton cricket club and as honorary president of the Picton association football club, but in terms of his avocations, his enthusiasm for golf was perhaps rivalled only by his enthusiasm for gardening: Bog was secretary of the Campbellford Horticultural Society in 1899; he worked his way up to president of the Picton Horticultural Society by 1904. But just when he became king of the horticultural castle, Bog was appointed Chief Inspector of the Standard Bank and had to move to Toronto.

Bog was the only member of the 1903 Executive Committee of the Picton Golf club not on the 1904 executive committee, presumably unable to serve because he was moving to Toronto.

As of 1905, Bog appears in directories for the city of Toronto, where he and his wife took up residence in “The St George Apartments.” They were listed thereafter in the “Society Bluebook” for Toronto, Hamilton, and London. He eventually retired to Picton, and when he died there in 1937, the newspaper observed two facts about him: first, “The Picton native was a financial wizard and he rose to become the chief inspector with the Standard Bank”; second, “Bog was a co-founder of the county’s first golf club, which was located on East Lake Road” (Picton Gazette, 1937, cited in Picton Gazette, 20 April 1917, p. 8).

Residing in Picton for just four years at the turn of the century, Bog nevertheless left a lasting mark on the history of the Picton Golf Club.

Like vice-president McLaren, 1903 and 1904 club president James Roland (or sometimes Rowland) Brown was never spoken of as a co-founder of the golf club, but he seems to deserve as high a standing as a founding father of the club as any of the members of the first executive committees.

Born in 1855, Brown was a Picton barrister and solicitor. He was called to the bar in 1881 and had practised law for many years before he took up golf. In the early 1880s, he established a law office in Picton, taking a partner there in 1885. He had been appointed King’s Council (or Crown Attorney) by 1892. In 1898 he was elected vice-president of the Picton Horticultural Society. He served again as vicepresident in 1904, when Bog was president. He himself had served as president in 1899, with Mrs. H.B. Bristol serving as his vice-president (her husband would become a member of the golf club’s executive committee in 1904). When Brown died in 1913, the Daily British Whig said that “Picton has lost one of its best citizens in the death of James Roland Brown, the well-known county crown attorney of Prince Edward County” (30 August 1913, p. 8).

The club secretary in 1903 and 1904 was Sandford C. Woodworth, born in 1849 in Crowland Township, near Welland, Ontario. Like Bog and McLaren, he had arrived in Picton only recently. He had begun his career as a teacher in the late 1860s in Elgin County, Ontario, teaching in Ontario’s Model Schools (county-based schools for training students to become teachers). By the early 1880s he had become a Principal and served as such at a number of schools in succession. In the late 1890s he was the Principal of a Model School in Welland, his old stomping grounds. But in 1901 he received an appointment in Picton. Like Bog and McClaren, one the first things he did when he arrived in town was to join the golf club. But he also loved soccer, serving as vice-president of the Picton association football club in 1902.

There were two other members of the 1903 executive committee, officers without Portfolio: Allison and McMullen. The newspaper gives them neither first names nor initials.

“Allison” seems to have been Malcom R. Allison, a barrister. He was the same age as McPhail, having been born 1864, which made him the second-youngest person on the executive committee. He was on the cusp of a substantial legal and political career. He was elected Mayor of Picton at the end of World War I. He was appointed a Crown Attorney, and he was appointed Clerk of the Peace for Prince Edward County. (In the Daily British Whig’s list of 1904 executive committee members, his name seems to have been misspelled as “M. Ellison.” There is no person named Ellison living in Prince Edward County at the time of the 1901 Canadian Census.)

Figure 18 Daily British Whig, 28 March 1904, p. 2. The information in this item seems to have been transmitted to Kingston via a poor telephone connection: Roland is misspelled Rowland; the wrong Porte is listed; Allison is misspelled Ellison; Pettet is misspelled Pettit; McMullen becomes M. Mullen.

The McMullen in question is probably one of two brothers: George Whitman McMullen or Harvard Conger McMullen. These brothers were two of the twelve offspring of Daniel McMullen, the first Methodist preacher in Prince Edward County.

George McMullen, born in 1844, left Picton at a young age for Chicago, and, along with another brother, became a successful businessman there by his mid twenties. In the 1870s, he became involved in providing American backers for the trans-Canada railway being built by John A. Macdonald’s government. McMullen’s exposure of unethical behaviour by Macdonald’s government and some of the businessmen with whom he was dealing led to Macdonald’s defeat as a result of what became known as the “Pacific Scandal.” Undeterred by his sullied reputation in Canada, McMullen prospered in dozens of other business ventures, focussing in Prince Edward County on the development of railway lines running north from Prince Edward County into southern Ontario’s mining areas, from which ore was brought to ports along Lake Ontario for delivery to American industries.

In later life back in Picton, McMullen also led another life as experimenter and inventor. In 1910, he had his lawyer, Picton Golf Club president J. Rowland Brown, negotiate options on boggy lands to the west of Picton along the East Lake Road. Purchasing a large part of this area, he built an experimental farm, machine shop, and laboratory. He and his three sons built huge dams and causeways to control water levels and stream water flow through areas growing various crops and hosting various species of waterfowl. They experimented with the growing of mushrooms, celery, ginseng, and sugar turnips; they produced maple syrup; they raised chickens; they manufactured explosives. They had a drying kiln where they dried various kinds of food, including eggs and milk. In 1914, McMullen and his eldest son George Barrett McMullen received a U.S. patent for a process enabling the preservation of railway ties by a special kiln-drying process that infused them with a creosote oil-mixture made from the wood tar of beech trees.

But then, in 1915, G.W. McMullen unexpectedly died of a heart attack while visiting his brother in Chicago, and then, just four years later, his son George Barrett McMullen, who continued his father’s work, also died prematurely. With the deaths of their most eccentric leaders, the McMullen family saw its experimental energies dissipate in the succeeding years, and eventually the property was sold.

Now government-owned, this site is known as the Beaver Meadow Conservation Area, and the remnants of the eccentric McMullen enterprise are fast disappearing under a tangle of vegetation.

Brother Harvard Conger McMullen, born in 1838, worked with George in the railway business in Prince Edward County. He never wandered far from home. In fact, he became a local politician. In 1904, he defeated a large number of opponents to win the contest for mayor of Picton. In 1908, not able to secure the nomination of the Liberal Party for the provincial election, he ran as an independent liberal, earning the scorn of his opponents: “As far as the candidature of Harvard McMullen, as an independent liberal, is concerned, he is being treated as a huge joke” (Daily British Whig, 23 September 1908, p. 1). But Harvard McMullen always soldiered on. In 1911, he became the agent in Prince Edward County for the Children’s Aid Society.

As George Whitman McMullen’s son George “Barrett” McMullen eventually also became a member of the club’s executive committee after his father died in 1915, I presume that it was probably his father who was the McMullen on the 1903 executive committee – father passing on to son not just his eccentric business activities, but also his love of golf. As George Barrett McMullen himself was just nineteen in 1903, however, it seems unlikely that he was the McMullen who was a member of that year’s executive committee.

The McMullen in question also seems to have served on the executive committee in 1904. Although there is a mysterious figure named “M. Mullen” in the Daily British Whig’s item about the 1904 executive committee, I assume this name to have been produced by a compositor’s mistaking a small “c” for a period, accidentally turning McMullen into M. Mullen. (In the 1901 Canadian Census, there is only one person named Mullen in Prince Edward County: Margaret Mullen, a servant.)

The 1904 Executive Committee

Bog was the only person from the 1903 executive committee who did not appear on the 1904 committee. Yet he was more than replaced on the 1904 committee; two more members were added to the new committee.

Figure 19 William Varney Pettet, 1857 - 1938.

One of the new executive committee members was a man named William Varney Pettet. Born in 1857, Pettet was by the end of the nineteenth century a farmerturned-politician. In a long campaign for the provincial legislature, he was from 1895 to 1896 the Prince Edward County candidate for the brand-new provincial Patrons of Industry party, winning election in 1896 to Queen’s Park. The party lasted for just a one term. He ran as an independent in 1900 and eventually became heavily involved in the provincial Liberal party.

He was perhaps a bit of a rascal, an inverse of Solomon in his practical wisdom:

in 1899, he was in charge of filling the vacant postmaster position in Picton, a patronage appointment for which there were between 30 and forty applicants – a difficult situation that he resolved by temporarily appointing himself postmaster! He was properly awarded the position in 1908 and served in it for six years.

Pettet went on to become secretary of the Prince Edward Liberal Association, holding the office for 20 years. He was also “paymaster with the old Bay of Quinte Regiment, holding the rank of Major” (Ottawa Citizen, 22 June 1938, p. 14).

Pettet regularly served on the executive committee of the Picton Golf Club for decades to come.

The Daily British Whig’s naming of W.J. Porte as 1904 treasurer of the Picton Golf Club is a mistake. William James Porte, who had immigrated to Picton from County Wexford Ireland in 1854 and worked in town for 45 years as watchmaker and jeweler, had died on Christmas morning of 1899. He had been joined in his business since the late 1870s by his son James H. Porte, born in 1862, who was presumably the one who had been elected treasurer of the Picton Golf Club in 1904. The Portes maintained their shop in the same downtown building that is still known as the Porte building today. The same year he was elected treasurer of the Picton Golf Club, Porte was also elected treasurer of the management committee of the Glenora-Adolphustown ferry. He was named a public-school trustee for 1905. In 1910, he was elected Mayor of Picton. More than twenty-five years after first being named to the executive committee of the Picton golf Club as treasurer, James Porte was elected president in 1930.

Figure 20 Hazard Benjamin Bristol, 1856 - 1936. Canadian Golfer vol 16 no 9 (January 1931), p. 693.

From the perspective of later club history, perhaps the most important new person named to the 1904 executive committee was Hazard Benjamin Bristol, an important Picton merchant and owner of Picton’s Canadian Department Stores, an enterprise that H.B. Bristol built up from the store his father had started in the 1850s and bequeathed to him in the early 1900s:

He was born at Newburgh in 1856, attended school until he was sixteen, and then spent some time upon the survey of the Central Ontario Railway. He served in the Council and was active in making changes to the electric light system, having served upon the Board of Commissioners of Light and Heat since 1900. It must be gratifying to father and son alike to note the great advance from the first general store at Hallowell Bridge to the metropolitan proportions of the triple fronted emporium of general dry goods now known as “A. Bristol & Son.” Mr. Hazard Bristol has been in partnership with his father since 1897, and in the conduct of his store employs … all modern methods of handling his wares and serving the public. He goes to Europe twice a year, to purchase goods, and has crossed the ocean a number of times. (William Felix Edmund Morley, Pioneer Life on the Bay of Quinte [Toronto: Rolph and Clarke, 1904], p. 164)

Hazard Bristol thereby became a very experienced traveller: in 1910, in fact, he set the record for the fastest trip from London, England, to Picton (he covered the distance in one hour less than seven days).

Bristol’s store was eventually sold to the Eaton’s company in 1928 (when Hazard Bristol retired after 53 years of business in Picton).

Bristol was much more than a local store owner. He was active in the Reform Association of the Liberal Party, being elected to its Council for Eastern Ontario in 1897. He was one of the first commissioners of Picton’s Public Utilities Commission. He was honorary president of Picton’s cricket club in 1902. He was a charter member of the Canadian Seniors’ Golf Association, and of course he has long been regarded as an important figure in the establishment of the Picton Golf Club. He served in various capacities on the club’s executive committee for three decades, frequently serving as president, and he also donated the original trophy for the men’s club championship

The First Clubhouse

The 1904 executive committee was the first to name a “ground committee,” and it was responsible for building the first clubhouse, about which the Kingston newspaper jested:

Figure 21 Daily British Whig, 1 June 1906, p. 8.

Figure 22 Ottawa Citizen, 21 June 1907, p. 8.

Regarding the value of a golf ball at the time of this outrage, consider the following facts.

In Ottawa at this time, George Sargent, the golf professional of the only golf club in the area, the Ottawa Golf Club, was offering a relatively large assortment of golf balls. The top brands were selling for $6 per dozen, and even “Old Ones” or “Recovered Balls” were fairly expensive. A single golf ball would have cost about 50 cents.

At this time in Almonte, Ontario, a town about the same size then as Picton was, the annual membership fee of the Almonte Golf Club was $2, so in that town a golf ball cost the equivalent of 25% of a person’s membership at the golf club!

Perhaps it is not surprising, then, that one of the most common prizes for winning a club tournament at the Ottawa Golf Club in those days was a single golf ball.

The Picton clubhouse is first mentioned in the Daily British Whig in 1904: “The golf club … intend erecting a small club house on their links this year” (27 May 1904). Perhaps its main function was simply to store clubs and balls, as was the case for one of the buildings at the Napanee Golf Club at this time.

Figure 23 The outbuilding for storing golf clubs at the Napanee Golf Club circa 1906. Club member Mary Vrooman stands in front of it. Photograph N-08790 courtesy of Lennox and Addington County Museum and Archives.

The newspaper indicates that the window pins of the Picton clubhouse were accessible to thieves from the outside, which suggests that the building was not designed with much concern for security.

It would have been quite understandable if in 1904 the Picton Golf Club had refrained from building a substantial clubhouse with kitchen, dining room, members’ lounge, and changing rooms, for it does not seem to have had much control over the land on which its golf course was laid out.

Yet we recall that after the club’s match against Napanee in May of 1904, “The ladies of the club served a delightful supper” (Daily British Whig, 26 May 1904, p. 8). Exactly one year later, the report after a similar match is the same: “The ladies of the club served a delicious supper after the game” (Daily British Whig, 27 May 1905, p. 4).

One supper was “delicious”; the other was “delightful.” The question is where the meal was served and where the meal was made.

Was the meal served at the clubhouse? Did the clubhouse have a dining room?

Was the meal prepared at the clubhouse? Did the clubhouse have a kitchen?

Whatever the size and amenities of this clubhouse, however, to have had any sort of clubhouse on a permanent golf course was golf luxury from 1904 to 1906 compared to the homeless condition of the golf pioneers who accompanied Macphail just a decade earlier in search of any “suitable open ground” for playing the royal and ancient game.

"First Directors" .... Really?

In its 1930 discussion of the early history of the Picton Golf Club, the Picton Gazette mentions that “The first directors were: H.B. Bristol, D.J. Barker, J.R. Brown, S.B. Gearing, W.V. Pettet, J. de C. Hepburn and M.R. Allison” (cited Canadian Golfer, vol 16 no 9 [January 1931], p. 693).

There are three new figures here: David John Barker, Sidney Barker Gearing, and James de Congalton Hepburn. Gearing had replaced Bog as manager of the Standard Bank; Barker was owner of the thriving Picton Foundry and possessed a new patent on an innovative stove design; Hepburn was the son of shipping magnate A.W. Hepburn.

James de C. Hepburn was also general manager and passenger agent for the Ontario and Quebec Navigation Company, and he was later elected MLA for Prince Edward County, serving briefly as House Speaker. He was also an officer of the Bay of Quinte Yacht Club at Picton. Born in 1878, Hepburn would have been in his late teens when Macphail began playing golf on “suitable open ground” in Picton and may have been one of the “young men of the town” that the presbyter proselytized on behalf of golf.

In the Picton Gazette article of 1930, there is no mention of McLaren, Woodworth, McMullen, Bog – all members of the executive committee in 1903, the latter of whom was later described by the Picton Gazette as a co-founder of the county’s first golf club!

Furthermore, note that one of these so-called “first directors,” Gearing, did not even come to town until 1905, when he arrived from Brighton to become Bog’s replacement as manager of the Standard Bank, so he was not even around when the not-yet-incorporated Picton Golf Club was electing its first executive committee in 1902.

He cannot have been one of the “first directors” of the Picton Golf Club.

Of course he could have been one of the first directors of the newly incorporated golf club of 1907, which is probably what the Picton Gazette’s list represents.

A New Location and the Prodigal Macphails

Fred Rose says that “The land to establish the golf course was obtained from Louise A. Stafford in 1907” (Picton Gazette 1980). The Picton Gazette says that the land for the golf club’s first nine-hole golf course was “purchased from John Laird and others in 1907” (cited in Canadian Golfer, vol 16 no 9 [January 1931], p. 693). Several parcels of land seem to have been put together at this time.

As we shall see, it turns out that two main parcels of land were bought at two separate times: first, a parcel on the south side of the highway; second, a year or two later, another parcel on the north side of the highway.

The clubhouse and the first nine-hole course were immediately built on the south side of the highway.

In a curious twist of fate, during the summer that the Picton Golf Club built its first nine-hole golf curse, D.J. Macphail returned to town. He was on another proselytizing mission:

Rev. D.J. Macphail, who is associated in the interests of the endowment fund of Queen’s University, has been in town the past week, looking up possible students to enter the Kingston college this fall. It is likely that Picton High School will send down some six students to augment the Prince Edward contingent already studying there. (Daily British Whig, 30 July 1907, p. 4).

Macphail had left town, but he had not been forgotten during the years he had been away, both because the friendships that he had made in town between 1892 and 1902 were strong and lasting, and because his name was in the news.