Caledonia Springs Golf Courses

CONTENTS

The Hotel’s Property and Amenities

Building a Golf Course in 1900

The Golf Grounds of the Grand Hotel

The Short Life of the First Golf Course

The Honorable Robert L. Borden’s Restoration by the Murray Course

The First Invitational Professional Golf Tournament in Canada (1909)

Jimmy Newman and Four Years of “Improvements”

The Other Professional Tournaments

Introduction

In 1900, at Caledonia Springs (a small village forty miles from Ottawa and seventy miles from Montreal, eight miles inland from the Ottawa River), the Grand Hotel Company built one of the earliest golf courses in Eastern Ontario.

Since the 1830s, hotels at Caledonia Springs had traded on the idea that the spring water in the area had special healing properties. So, by 1900, if a resort offered restorative hydrotherapies that were to be enhanced by recourse to modern recreational facilities, it pretty much had to have a golf links.

The upshot of this venture into golf course construction by the Grand Hotel was that when the property was purchased by the Canadian Pacific Railway Company in the early 1900s, and thereby incorporated into the company’s coast-to-coast chain of hotels, golf architects of considerable substance – such as Charles R. Murray and Thomas Bendelow – were brought in to design new golf courses at Caledonia Springs, and the hotel eventually became so enthusiastic about golf that it sponsored the first “invitational” professional golf tournament ever held in Canada.

In 1914, the Caledonia Springs Hotel Golf Club had become so well-established that it officially joined the Royal Canadian Golf Association.

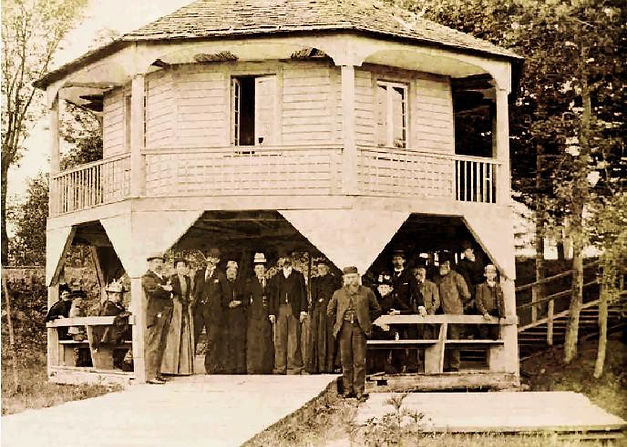

In 1915, however, the hotel went out of business and closed its doors forever. And soon those doors fell off, the wood rotted, and the concrete crumbled. Today, hardly a trace of the hotel’s many buildings remains, except for one of its “water houses” where guests once accessed the healing water piped into this building from one of the hotel’s sulphur springs and from one of its saline springs.

Figure 1 The photograph on the left shows the exterior of the last surviving water house of the Caledonia Springs Hotel. The photo on the right shows the interior of this building, with the words “Magi Springs” still legible on the floor, as well as the word "Sulphur" on the floor at the left side of the tiled tub (indicating the pipe that still feeds water into the building from a sulphur spring) and the word “Saline” on the floor at the right side of the tiled tub (indicating the pipe that still feeds water into the building from a saline spring).

There is now no physical trace of the nine-hole golf course that ran past this water house.

But the newspapers and magazines of the day carry textual traces of the story of golf at Caledonia Springs. And this story includes the names and exploits of some of the most significant professional golfers in Canada and the United States in the first two decades of the twentieth century.

It is time that the story of the Caledonia Springs golf courses was told again.

The Springs

Legends about the original discovery of the special medicinal properties of the waters of Caledonia Springs are many. Whether the supposed medicinal properties of the water were first identified by indigenous peoples or by European settlers is not clear. The Iroquois, for instance, are said to have known of the health-giving properties of the springs and to have introduced them to European settlers in the early 1800s. What is indisputable, however, is that it was the settler community that figured out how to turn the water into money by building a hotel at Caledonia Springs in 1835.

By the 1840s, word of the wonder that was the resort at Caledonia Springs reached London when the resort was visited by Canada’s Governor-General, Sir Charles Metcalfe:

[From Ottawa] the Governor-General continued on his route to Montreal, but on arriving at that part of the canal from which the road to the Caledonia Springs proceeds, he turned off, and reached that place in a few hours by stage.

This delightful spot – where every recreation is to be found, and where every luxury and want is provided by its indefatigable proprietor, for those who may be in search of enjoyment, or for the more unfortunate, though the more benefited, invalids who may be attracted there by the known virtues of its waters – is the resort of great numbers from the United States as well as from all parts of the province, and, although situated in the midst of the forest, may very justly be called the Cheltenham of Canada. (Morning Post [London], 27 September 1843, p. 7)

Figure 2 The original hotel at Caledonia Springs as depicted on the cover of William Parker's The History, Rise and Progress of the Caledonia Springs, Canada West (Montreal: James Starke, 1844).

Forty years later, the resort was still well-known in England, now “dubbed the Saratoga of Canada,” although a snarky writer characterized it as having become the resort of the pretentious: “here flock all the fashionably halt, the fashionably maimed, and the fashionably blind from all parts of the Dominion” (Manchester Weekly Times, 5 September 1885, p. 14).

By 1875, a new hotel built by King Arnoldi had opened. Seen below, it was raised on the site of the original building and was known as the Grand Hotel (one of its main springs was located in front of the hotel where the two-storey pavilion appears on the right side of the photograph below).

Figure 3 The Grand Hotel of Caledonia Springs, circa 1875. Library and Archives Canada.

In 1905, the Grand Hotel was sold to the Canadian Pacific Railway Company and renamed the Caledonia Springs Hotel, but the C.P.R. continued to promote the spring waters.

The hotel’s advertisements continued to cite testimony by experts about the water’s healing properties:

Authority Speaks

Extract from an Article by Sir James Grant, M.D., F.R.C.P. Lon., K.C.G., M.P.

One of the chief watering places of the day is MAGI Caledonia, the seat of the springs, at present attracting considerable attention.

To see the sickly arrive each day, unable to walk, assisted by crutches and such like, and in the course of one week, or so, to observe the changed condition, active, lively and nimble, walking about unaided by anything except the props of nature, is proof positive of the curative influence of these waters.

Jaundiced faces, changed to clear skins, swelled limbs reduced to their natural size, distorted joints regaining their normal elasticity, and, in fact, the general transformation from a state of infirmity to activity, so pointed that one cannot avoid coming to the conclusion that in the MAGI Caledonia Springs, nature has placed at the disposal of the public one of the grandest levers possible for the restoration of health. (Quebec Daily Telegraph, 22 June 1905, p. 4)

By the beginning of the nineteenth century, the waters of Caledonia Springs were shipped world-wide.

Figure 4 The shipping platform at Caledonia Springs. Magi Caledonia Springs brochure (1899), p. 8

Although shipped far and wide in barrels, the water was sold in attractive bottles with labels proclaiming its origins in Caledonia Springs.

Figure 5 Surviving bottles of Magi Caledonia Water from Caledonia Springs.

From the point of view of the present essay, however, the most important aspect of the famous water at Caledonia Springs is that what was not bottled for sale, or fed into in salubrious mineral baths, flowed freely in creeks that meandered across the property of the resort – creeks that provided excellent water hazards for the three golf courses laid out on the resort site between 1900 and 1915.

Good for the health of the hotel’s visitors, the water was bad for the golfer’s scorecard when confronting the player as what newspapers of the day called the golf course’s many “water jumps” (Montreal Star, 17 August 1909, p. 2).

The Hotel's Property and Amenities

Figure 6 The 1899 brochure of the Grand Hotel Company, Caledonia Springs.

In 1899, the Grand Hotel Company published its largest brochure to date: eighteen pages of text, photographs, and maps that described its location, property, accommodations, baths, and recreation facilities (the cover of this brochure is seen to the left).

Competition with other resorts for visitors from Ontario, Quebec, and the American Northeast was intense, so the company strove to distinguish itself from the dozens of other hotels advertising in the major newspapers of the region’s cities.

The Grand Hotel’s greatest claim to distinction was the salubrious waters of its numerous springs (billed as “Fountains of Health”), so it listed the ailments that could be treated by its hydrotherapies:

the waters could relieve gout, rheumatism, sciatica, lumbago, neuralgia, jaundice, biliousness, dyspepsia;

they could treat all derangements of the stomach, indigestion, nausea, acidity, want of appetite, constipation, kidney complaints, disordered liver, diseases of the urinary organs, passages of gall stones;

the baths were good for eruptions and skin diseases, scrofula, ivy poisoning, inflammation of the eye, ague, spinal irritation;

a course of drinking the waters and bathing in them could cure want of sleep, nervousness, St. Vitus’s dance, even teething in children;

women would find the hydrotherapies capable of addressing “female complaints,” hypochondria, hysteria, barrenness;

the waters could address the effects produced by the improper use of mercury, cases of wasted constitution, and so on.

But the hotel also needed facilities for the entertainment of those who accompanied the “invalids” seeking restoration from the hydrotherapies, and so the hotel became increasingly interested to attract those who wished simply to enjoy a vacation away from the oppressive summer heat of the cities:

What the Hotel and Grounds Comprise

Adjoining the Grand Hotel is a commodious Amusement Hall with Gymnasium, Dancing Floor, Bowling Alleys, Billiard Room, etc., …

Figure 7 A 1911 view of one of the billiard rooms of the Caledonia Springs Hotel Company, successor to the Grand Hotel Company. Postcard dated December 1911.

The grounds are tastefully laid out with walks, shade trees, Tennis, Croquet and Quoit Lawns….

Figure 8 A photograph of the avenue leading to the springs in front of the hotel from the Handbook to Caledonia Springs for 1896, p. 3.

The property of the Company comprises about 200 acres; a grove occupies about 30 acres, and the enclosure around the Grand Hotel about 25 acres. In the latter is the Post Office, Protestant and Catholic churches, etc.

Figure 9 From the Handbook to Caledonia Springs for 1896 (pp. 7 & 6, respectively) a photograph of the Catholic Church (left) and a photograph of the inside of the Protestant Church (right).

Many visitors seem to put in their entire stay without ever thinking of quitting the grounds, immediately outside of which is the train station….

Figure 10 Caledonia Springs train station 1910.

The Grand Hotel has accommodation for 250 guests.

Figure 11 One of the hotel's parlours. Postcard dated December 1911.

It is most conveniently laid out and comfortably furnished, has spacious, airy halls, bedrooms, parlors, reading and card rooms; the dining room is sufficiently large to seat all residents at the same time. The kitchen, pantries and other domestic offices are very complete. Many changes and improvements in every department recently made add greatly to the comfort and convenience of this House….

The Baths are in the main building of the Grand Hotel; the Gas, Saline and White Sulphur Springs immediately in front…. The Duncan Springs … about 2 miles distant….

Figure 12 From the Handbook to Caledonia Springs for 1896 (p. 2), a view of the springs in front of the hotel (the roofline of which appears above the trees in the background). In the bottom right corner of the photograph, two men put spring water into containers.

Situation, Characteristics, Etc.

The site of Caledonia Springs is in the midst of an elevated plateau; the country generally has been well cleared and is almost devoid of bush or trees, except such as are preserved in the immediate vicinity for ornamental purposes.

There is an almost constant breeze and excessively warm weather is rare. The soil is impregnated with Saline material and the air strikes all as having great similarity to that of the seaside. At night the temperature is always agreeable and blankets to the beds are usually a necessity…. The drainage of the grounds, together with the clearing up of the surrounding country, has practically banished the mosquito…

Figure 13 A view to the south-west from the roof of the Grand Hotel. Handbook to Caledonia Springs for 1896, p. 14.

The proprietors carry on extensive farming and keep a large stock of cattle, enabling guests to be furnished with the best and freshest products in this line…. (pp. 5-7)

Figure 14 A view from the roof of the Grand Hotel looking toward the Ottawa River to the northeast over some of the resort’s farm buildings to the extreme right, as well as some of the other buildings of the village (including some of its cottage hotels). Handbook to Caledonia Springs for 1896, p. 2.

The farming operation established by the Grand Hotel Company and maintained by its successor, the Caledonia Springs Hotel Company, increased in size and scope every year.

By 1910, the farm was supplying products to other of the C.P.R.’s hotels. When members of the Ottawa Press Club visited the resort in the spring of 1910, some going “to the elaborate swimming bath, some to the billiard tables, others to the bowling alleys,” and so on, they all later toured “the big farm buildings … of the big 150-acre farm which is so well managed … that the whole institution is self sustaining” (Ottawa Citizen, 16 May 1910, p. 7).

Figure 15 Early 1900s postcard shows the view from the hotel roof to the northwest. Seen in the foreground is the part of the hotel’s farm known as the hennery. The dirt road between the hotel and the hennery is the Leduc Side Road, which runs up to the Adanac Road to the right (along which the farm houses are ranged across the top of the postcard).

Although the great Caledonia Springs hotel was already virtually self sustaining by 1899, what selfrespecting summer resort could make a pretense of catering fully to the needs of holiday seekers if it did not have facilities for golfers?

And so, in 1900, the last year of the nineteenth century, there would be a golf course laid out by the Grand Hotel Company at Caledonia Springs.

Eastern Ontario Resort Golf

On 21 May 1900, the Grand Hotel Company announced that “All amusements usual at summer resorts are found at Caledonia Springs. With the opening of the season, a golf club is to be formed from among the visitors and the new links inaugurated” (Gazette [Montreal], 21 May 1900, p. 4).

At Caledonia Springs, golf had been missing, but now it was found. The Grand Hotel thereby joined in the North American golf fad of the late nineteenth century, which began in the United States in the early 1890s and soon spread to Canada.

Golf, mind you, had certainly become established in three major Canadian cities almost a generation before it became established in the United States: twenty years before the fad began, golf clubs had been established in Montreal (1873), Quebec (1874), and Toronto (1876).

Figure 16 Royal Montreal Golf Club, 1882.

But when the popularity of golf spread south from Scotland into England in the early 1890s, resulting not just in the construction of many new golf courses on the links land of coastal England, but also in the construction for the first time of many inland courses, interest in the game was aroused in the United States. The development of architectural strategies for designing golf courses on non-links land was the key, for North America had little accessible links land but a virtually limitless supply of inland real estate.

Reflecting on the astonishing speed with which the game of golf spread throughout the United States from 1893 to 1895 – as what the San Francisco Examiner called “the fad of the hour” (30 June 1895, p. 32) – the New York Sun observed:

Golf is outstripping all the outdoor games just now in its rapid growth. It took years to fully acclimatize tennis, and, with the exception of baseball, which is a home product, the other fresh-air games and recreations have only become popular by slow degrees. But golf is advancing with seven-league strides, like Jack in the fairy tale, and will soon travel the continent over, from the Arctic line to the Mexican border, for the game is spreading through Canada as well as the United States. (Sun [New York], 8 March 1896, p. 9)

This golf fad perhaps first crossed from the United States into Ontario at Hamilton in the fall of 1894. But it quickly spread eastward through Ontario, first at Cobourg in 1895 (where regular summer visitors from Rochester were among those interested in the formation of Cobourg’s first golf club that year), and then at Cornwall and Port Hope in 1896. Golf enthusiasts in Merrickville laid out a golf course in the spring of 1897. At the same time in Napanee, the present golf club was established to play golf on the very land on which it still plays today. Picton also first organized a golf club in October of 1897 (Napanee Express, 8 October 1897, p. 1).

And we read in the same month that “A golf club is to be organized in Smiths Falls” – an effort that would soon produce the Poonahmalee Golf Club (Almonte Gazette, 9 October 1897, p. 7).

Figure 17 Two unidentified women on the first tee of the Poonahmalee Golf Club of Smiths Falls, Ontario, in the early 1900s.

In Perth, although Captain Roderick Matheson had laid out a three-hole golf course on his farm in 1890 for the use of six or seven of his friends shortly after he had first encountered the game himself in Montreal, it was only in October of 1897 that the Almonte Gazette observed that interest in the game had finally become so widespread in that town that “Perth is to have a golf club” (29 October 1897).

Brockville was only slightly behind the curve:

Figure 18 An unidentified woman putts on the ninth green of the Links O' Tay golf course in Perth, Ontario, in the early 1900s.

its first golf club was organized a few months later in the spring of 1898 (Ottawa Journal, 28 April 1898, p. 6). And Carleton Place, known as “the junction town,” also became interested in the game in 1898, prompting the newspaper in the rival town of Almonte to mock its neighbour for its pretentiousness: “The junction town is putting on frills. It is to have a golf club” (Almonte Gazette, 2 September 1898, p. 8).

Casting an equally ironic eye on the golf fad, the Arnprior Chronicle implied that sportsmen and sportswomen of Arnprior were wise to resist the new sport in favour of a more traditional one:

“Instead of going in for golf, the greatest fad of the day, Arnprior has reverted to lawn tennis” (cited in the Almonte Gazette, 6 July 1900, p. 3). The Chronicle, however, spoke too soon: Arnprior had its own golf links less than a year later (Ottawa Citizen, 1 June 1901, p. 10).

Perhaps, so far as our understanding of the development of golf at Caledonia Springs is concerned, more important than the general spread of the golf fad through the towns of Eastern Ontario was the fact that hotels along the Ottawa River and in the American and Canadian Thousand Islands had also established golf courses by the turn of the century. As James Shields Murphy, editor of The Golfer, observed in the spring of 1898, “Probably the list of summer hotel golf links in the United States will next season eclipse that of the other side [Great Britain and Ireland], judging by the spread of the game at present. The amount of money the hotels are spending to lay out links equals that spent by many clubs” (vol 6 no 6 [April 1898], p. 249). American and Canadian summer hotels had to build golf courses to attract wealthy visitors from the eastern United States, Ontario and Quebec who had become enthusiastic members of golf clubs in their hometowns and now expected to be able to play golf when they were on vacation.

This was the demographic that the Grand Hotel of Caledonia Springs sought to attract.

But competing with the Grand Hotel for these guests was the Hotel Victoria in Aylmer, Quebec. Built in 1897, the hotel by 1899 hosted the Victoria Golf Club, which was formed in February of that year. Its golf links had been laid out by the spring of 1899, stretching for about a mile from the grounds of the hotel northwest along the shore of Lac Dêschenes (a widening of the Ottawa River). The golf course began and ended within a few minutes’ walk of the hotel’s front door. Play was underway by the end of April.

Figure 19 A postcard view, circa 1900, of the lawns on the golf-course side of the Hotel Victoria. The first tee and final green of the golf course were not far from where the family in the photo is shown.

In the Montreal Star’s news of sports played at the resorts in the “Thousand Islands” during the summer of 1899, it reports that “Golf is resolving itself into perhaps the most popular athletic sport. It is probable that matches will be arranged between several clubs which have been organized throughout the islands” (5 August 1899, p. 8).

By the spring of 1900, the Algonquin Hotel on Stanley Island (which was in the middle of Lake Francis, a widening of the St. Lawrence River near Cornwall, Ontario) had laid out a nine-hole golf course on its 50-acre property. It would be called the “Stanley Island Golf Cub” for many decades.

Figure 20 The 300-room Algonquin Hotel on Stanley Island, circa 1900.

In its first year of operation, the Stanley Island Golf Club became so confident of both the golfing abilities of its members and the quality of its new golf course that it challenged the Cornwall Golf Club to a match.

The challenge was accepted, and in announcing the match, the Montreal Star reported: “The links are in excellent condition” (7 July 1900, p. 9).

Like the Montreal Star, Kingston’s Daily Whig reported in 1898 that “Golf is the coming game among the islands” and the next year observed: “Golf is booming at Thousand Islands resorts. There are flourishing clubs at Alexandria Bay and Round Island Park” (11 July 1898, p. 2; 2 August 1899).

There were other golf courses opened at this time in the Thousand Islands, too, but it may have been the golf course at Round Island that was the greatest spur to the Grand Hotel Company’s decision to build its own golf course in 1900.

A hotel had been established on Round Island in 1878, and since 1888 it had been known as the Frontenac Hotel, but in 1898 it was acquired by a new owner who completely renovated the building and re-opened the hotel as “The New Frontenac” in the summer of 1899.

Figure 21 Ottawa Journal, 18 June 1899, p. 8.

A golf course may have been laid out on Round Island a year before, but, if so, it was also thoroughly renovated and redesigned between 1898 and 1899. The new golf links were prominently featured in the hotel’s 1899 advertisements(seen to the left), the words “NINE HOLE GOLF COURSE” being emphasized.

This golf course was widely discussed in newspapers and magazines after its opening in 1899:

The golf links of the New Frontenac, which were laid out by Willie Dunn of New York, are at last completed. The course is one of the finest in the country. The links [i.e., the golf holes] average nearly three hundred yards each and the many bunkers, as well as natural hazards, will test the skill and try the patience of the most experienced golfist. (Montreal Star, 22 July 1899, p. 9)

Figure 22 Willie Dunn (1864-1952). Golf, vol 5 no 3 (September 1898), p. 175.

For the Montreal Star to have observed that “The course is one of the finest in the country” is one thing. But it is a different order of magnitude for New York newspapers to have drawn this golf course to the attention of readers in “The Big Apple,” where Willie Dunn was regarded as the best golf course architect in North America.

Born in England (although a descendent of a great Scottish golfing family), Dunn had been based in New York since his appointment as golf professional at the Shinnecock Hills Golf Club in Southampton, Long Island, in 1893 and had won notoriety for his design and construction of the most expensive golf course ever made: the Ardsley Casino Club golf course that he built between the fall of 1895 and the spring of 1897.

Of Dunn’s work on Round Island, we read in the New York Tribune as follows:

One of the most attractive features of the New Frontenac is its excellent golf course laid out at great expense by “Willie” Dunn of New York. A golf club was formed early this month, and the semi-weekly tournaments contribute largely to the interest of the hundreds of guests that have enjoyed and are enjoying the hospitality of the house. (New York Tribune, 20 August 1899).

Brooklyn Life observed:

Golfers will find every preparation for their comfort. The links are adapted by nature for the sport, the hazards being mainly natural. The course was laid out and constructed under the personal supervision of Mr. Willie Dunn, and is in charge of a professional greenkeeper; and the necessary paraphernalia can be procured at the hotel. (Brooklyn Life, 10 June 1899, p. 4)

And for the growing numbers of visitors to summer resorts who were now putting golf above all when it came to vacation planning, there was an even more enthusiastic review in in September of 1899 by Paul R. Clay in the magazine called Golf, which was widely read by golfers:

Of the notable golf courses laid out this year, the blue ribbon for picturesque location, and general charm and attractiveness, must go to the course laid out by Willie Dunn at the New Frontenac, on Round Island, one of the far-famed Thousand Islands of the St. Lawrence…. The course is elliptical, roughly following the contour of the island, and measuring 2,500 yards….

Figure 23 A postcard map circa 1900 of the New Frontenac’s “Frontenac Island Golf Course.”

The surface is rolling, broken in places by short, sharp ledges, and with the exception of a few short stretches is covered with springy turf.

The hazards are natural, save for four picturesque [artificial] bunkers through the more open green [the phrase “open green” refers to fairways]….

The tee for the sixth hole is prettily perched on the crest of a ledge and favors a clean, long drive to the green 200 yards away.

A topped ball will, however, land in a sand gully ….

Figure 24 A view of Dunn’s Round Island golf course. Golf, vol 5 no 3 (September 1899), p. 196.

The eighth tee is also very picturesque, lying in a clump of trees on a point of land hanging out over the water.

A long sandy rise stretches out from the tee for nearly a hundred yards, but from the top a good turf runs level to the green. The hole measures 304 yards….

Figure 25 A view of a teeing ground at Dunn’s Round Island golf course. Golf, vol 5 no 3 (September 1899), p. 197.

The weekly tournaments of the New Frontenac Golf Club … are prominent features of the life of the hotel, and the members of the club and the players numbered among the guests at the New Frontenac are very enthusiastic in their praise of the course. Walter Fovargue, of the Cleveland Golf Club, is greenkeeper, and he has with him an expert club maker and repairer. (Golf [September 1899], vol 5 no 3, pp. 196-98)

Did the Grand Hotel Company notice not just the good reviews that the new golf course on Round Island was receiving, but also the repeated observation that the golf course was a big attraction for the hotel’s guests?

By the turn of the century, golf courses had become so ubiquitous at summer hotels and resorts that jokes began to be published for the sake of those who pretended it was saner to resist the golf fad:

“You are having a remarkably successful season, Mr. Whicks,” said Atterbury.

“Yes,” replied Mr. Whicks. “I advertised this place as the only hotel in the mountains that had no golf-links, and we have had nine applications for every room in the house.” (Almonte Gazette, 15 September 1899, p. 1)

At the end of the 1899 resort season, the Grand Hotel at Caledonia Springs found itself standing out as one of the few resorts drawing guests from Ottawa, Montreal and the American Northeast that could not offer its guests a golf course. In the face of the success of golf courses at nearby resorts in Quebec, Ontario, and New York, the directors of the Grand Hotel Company knew that they could not follow the strategy of the mythical manager Mr. Whicks: they had to lay out a golf course.

Interestingly, after its golf course was built in the spring of 1900, the Grand Hotel’s advertisements throughout the ensuing summer season specifically mentioned that its facilities now included those for “Golf and concomitants of the other Spas,” suggesting that its construction of a golf course was indeed part of a determined strategy to keep up with developments in premier summer hostelry at “the other” spas and resorts with which it was competing.

Building a Golf Course in 1900

The first golf course at Caledonia Springs was probably not a very sophisticated layout.

A farmer’s pastureland was generally chosen for a golf course at that time because the land had already been cleared of trees and had well-established pasture grass growing on it – grass that only needed to be cut regularly in order to produce a decent grass surface from which to play a golf shot. No earth was moved to add slopes or mounds to a fairway (which was called the “fair green” in those days). And greens were not built up by moving earth and shaping an undulating surface. Walter J. Travis claims that it was only as a result of his own work in 1906 that North American golf architects began to raise greens above the level of the fairway and to build into them challenging contours and elevation changes; before this, says Travis, golf course designers generally accepted the lie of the land as they found it and looked for flat areas with good drainage as possible green locations (See Walter J. Travis, “Twenty Years of Golf,” American Golfer [9 October 1920]).

As Ottawa Citizen golf writer Bruce Devlin observed, putting greens on Ottawa area golf courses were not much different from fairways until around 1912:

The building of greens nowadays [1923], with the extensive backing-up and contouring necessary to the requirements of modern golf, is not the simple matter it was a decade ago. Then, the ground merely was cultivated, the line between fairway and green being but a difference in grass texture. But now, each putting surface is constructed from accurately drawn plans, each conforming to the type of shot required and each having its own individual characteristics. (Ottawa Citizen, 17 August 1923, p. 11)

In 1900, putting greens were generally located on a relatively flat and level area of a field. Cut shorter than the fairway grass by means of a mechanical mower or a scythe, a putting green was usually cut in the shape of a square or rectangle, with sides of perhaps 20 to 30 feet.

Figure 26 Scyther at the Ottawa Golf Club on Aylmer Road, Gatineau, Quebec. Circa 1904.

The preference was not for an undulating or wavy surface that would require calculation of how the golf ball would break this way or that on its way to the hole, but rather for a surface as flat and as level as that of a billiard table on which a ball would roll precisely where it was aimed.

The putting green would be compacted to produce a relatively smooth putting surface on which the bounce of a gently rolling ball would be minimized. A crew might roll the entire putting surface with a heavy barrel-shaped cylinder on a horizontal axis attached to a handle (designed to be pulled by two men), it might thoroughly soak the putting surface with water, then place planks over it and pound the planks with a heavy object, or it might pound every square foot of the putting surface with a heavyhandled instrument with a flat square bottom, as in the photograph below.

Figure 27 Around 1900, unidentified groundmen at work on the construction of a golf green, using s shovel, a rake, and two square-bottomed pounding tools. Michael J. Hurdzan, Golf Greens: History, Design and Construction (Wiley 2004), chapter 1.

In the late 1890s and early 1900s, the construction of a golf course by these methods could be completed in less than two weeks from start to finish, after which play on the course would commence immediately.

In the photograph below, we can see an example of a golf course laid out in the late 1890s at Penetanguishene, Ontario, by a summer hotel comparable to the Grand Hotel at Caledonia Springs.

Figure 28 Golf links of the Penetanguishene Hotel, Ontario. Golf, vol 5 no 1 (July 1899), p. 10.

The putting green visible in the photograph was merely a small circle of grass cut shorter than the surrounding fairway. There are no artificial bunkers near the green. The land is flat and relatively featureless. Previously, it had probably been pastureland. I expect that the first golf course at Caledonia Springs looked a lot like the one above.

Who was the Architect? Not!

The owners of the Grand Hotel would have known that the well-received golf course commissioned in 1898 by the owner of the New Frontenac Hotel had been laid out by the most famous golf architect in North America at that time: Willie Dunn, Jr.

So, who did they hire to lay out their own golf course?

In 1900, laying out a golf course generally fell within the job description of the golf professionals who were coming to North America from Scotland and England at that time. Dunn himself had come to New York in 1893 to serve as a golf professional for the Shinnecock Hills Golf Club. He immediately added six holes to its existing twelve-hole course. As demand for golf courses in the American Northeast exploded from the mid-1890s onward, Dunn stepped into the role of golf course architect with a confidence that soon became a swagger.

In Canada, however, there were only about six officially established golf professionals when the Grand Hotel Company looked for someone to lay out its golf course, and few of then had yet established a reputation as a golf course architect, so it is not clear that the Grand Hotel Company, which was looking to compete with first-class resorts, would have hired any of these six golf professionals to lay out a golf course that was going to have to compete with nearby golf courses laid out by Willie Dunn.

Figure 29 John M. Peacock. Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 27 December 1910, p. 23.

A notable golf professional in the Maritimes, hailing from St Andrews, Scotland, was John M. Peacock of the Algonquin Golf Club at St Andrews, New Brunswick. He served at the Algonquin Golf Club for seven months each summer but then went south for five months each winter to serve as a golf professional at the famous Pinehurst Resort in North Carolina. He would serve there alongside fellow golf professional and prolific golf course designer Donald J. Ross after the latter’s arrival in the early 1900s.

Peacock would lay out several golf courses in New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island in the early 1900s, but he is not known to have travelled east to lay out golf courses in either Quebec or Ontario at this time. In 1900, Peacock would not have been a likely candidate for the commission to lay out the Grand Hotel’s first golf course.

Figure 30 Arthur W. Smith. Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 5 September 1901, p. 7

As of 1895, the Toronto Golf Club employed a well-established golf professional named Arthur W. Smith. He was certainly capable of designing a golf course.

Born in 1874 in Great Yarmouth, Norfolk, England, Smith became an accomplished tournament playerin Canada and the United States. Her played in an early international tournament between Canadian and American professionals at Niagara Falls in 1896, he won the Western Pennsylvania professional championship twice in the early 1900s, he won the Ohio professional championship several times after that, and in 1905 he won the Western Open, which was in those days regarded as a “Major” championship.

While at the Toronto Golf Club, he laid out eighteen-hole courses at Toronto, Rosedale, and Rochester, and he laid out nine holes in Hamilton. But he left Toronto at the end of the 1899 golf season and went to the Edgewood Golf Club of Pennsylvania in the spring of 1900. He was not available to do the work at Caledonia Springs.

Figure 31George Cumming. Canadian Magazine, vol 17 (May to October 1891), p. 346.

From the dozens of applications from British golf professionals that the Toronto Golf Club received during the winter of 1900 in the competition to replace Smith, the club chose twenty-year-old George Cumming of Glasgow, Scotland.

In the spring of 1900, young Cumming had not yet arrived in Toronto when the Grand Hotel Company went looking for a golf course architect, and he was still unpacking his bags, so to speak, when the first Caledonia Springs golf course was laid out. He would not have been the begetter of the first golf course at Caledonia Springs.

On the one hand, as an architect, Cumming would have been too unknown and too untried for the Grand Hotel’s purposes.

On the other hand, even if he had been asked to lay out such a golf course, as the 1900 golf season was beginning, Cumming would have been too busy learning the operation at the Toronto Golf Club to have left town to lay out a golf course in Eastern Ontario.

Figure 32 Nicol Thompson, circa 1900.

Figure 33 David Ritchie. Canadian Magazine, vol 17 (May to October 1891), p. 347.

The Hamilton Golf Club golf professional in 1900 was Nicol Thompson (who was an older brother of Stanley Thompson). He had begun his career in golf as a caddie at the Toronto Colf Club in the 1890s. He was then invited by Arthur Smith to serve as his apprentice:

Thompson learned all he knows of the professional’s duties from Smith …. Thompson, who was born in Scotland, … spent four years in the same golf club repair shop with Smith. Arthur Smith recommends him as a strong player and conscientious instructor. (Pittsburgh Weekly Gazette, 10 February 1902, p. 7)

Thompson was appointed golf professional at Hamilton in 1899 when he was just nineteen years old. Although he would later design many golf courses on his own and then form a golf design and construction company after World War I with George Cumming and Stanley Thompson, he had not yet designed a golf course by 1900, so twenty-year-old Nicol Thompson would not have been the one called upon by the Grand Hotel Company to lay out its course.

David Ritchie was the golf professional at the Rosedale Golf Club in Toronto, and he would become a minor golf architect in due course: laying out of a nine-hole course for the Bruce Beach Golf Club on the shores of Lake Huron in 1907 (and again laying out a new nine-hole course for the club in 1929), laying out a nine-hole course for the Stratford Country Club in 1913, redesigning a nine-hole course for the Kincardine Golf Club in 1920, and laying out a seven-hole course for the Listowel Golf Club in 1920.

Born in a home overlooking the Old Course at St Andrews, Scotland, in 1873 (the son of a stone cutter), Ritchie had learned how to play golf by age three, but when his family immigrated to Toronto in the late 1880s, his interest was not golf, but literature and theology, so after several years of work as a plumber he became a student at the University of Toronto in 1896, engaging in three years of course work preparatory to study at Knox College to qualify for ministry in the Presbyterian church.

At the University of Toronto, he laid out a ten-hole golf course on the university grounds across Devonshire Place and Taddle Creek ravine for student and faculty golfers.

The golf-mad registrar of the University of Toronto convinced him during his first year of study that the best way to finance his university education was to serve as the golf professional of the Rosedale Golf Club. In Britain’s Golf Illustrated, he was celebrated by Miss A.B. Pascoe in her article on “Ladies Golf in Canada” for his work with Rosedale’s women members: “The Rosedale ladies get good coaching from D. Ritchie, a native of St Andrews, who is a divinity student at Knox College, and the local ‘pro’” (18 January 1901, p. 51).

Ritchie entered Knox College at the turn of the century but remained Rosedale’s golf professional. Note that he had not apprenticed as a golf professional in Scotland (and so, for instance, another man, John Dixon, had to serve as the greenkeeper at Rosedale). Ritchie had established no reputation as a golf course designer by 1900, so he would not have been sought out by the Grand Hotel Company as their architect in the spring of 1900. (Ritchie later duly became a minister in the Presbyterian Church of Canada, his first posting being in Saskatchewan, where he won the provincial amateur golf championship before he returned to Ontario in 1911.)

There were two golf professionals working relatively close to Caledonia Springs in 1900: Tom Smith, of the Royal Montreal Golf Club, and William Divine, of the Ottawa Golf Club. Since the Grand Hotel drew most of its guests from Montreal and Ottawa, among whom were many prominent members of the Royal Montreal Golf Club and the Ottawa Golf Club, the hotel’s directors may well have sought advice fromthe Montreal and Ottawa clubs as to who might be asked to lay out their golf course. And it is likely that the clubs would have agreed to loan their golf professionals to the Grand Hotel for such a job – had the club thought its golf professional up to the task! (Royal Montreal, for instance, sent their pro James Black to Almonte to lay out the town’s first golf course in 1902, and the Ottawa Golf Club sent its pro George Sargent to lay out the same town’s new golf course in 1907.)

Although Divine had been trained as a golf professional in North Berwick, Scotland, and was licensed as one of the few freelance golf professionals entitled to work on the town’s West Links, he had just arrived at the Ottawa Golf Club in the fall of 1899 or spring of 1900. The club would not yet have drawn any conclusions as to his abilities as a keeper – let alone as a designer – of golf courses. Within a short while, it seems that Divine came to be regarded by many members as merely a “ground man.” And when the club purchased its new golf course property on the Aylmer Road at the end of 1902, it did not have Divine design the new course, but rather brought in Tom Bendelow. At the end of the 1903 season, it decided to replace Divine with a “first-class professional.” So, when the Grand Hotel Company began looking for a golf architect to lay out its first golf course, Divine was just as unknown and untried as Cumming, Thompson, and Ritchie. It is unlikely that he was called down to Caledonia springs to lay out a golf course.

A similar story can be told of Tom Smith, the older brother of Arthur Smith.

Figure 34 Tom Smith. Pittsburgh Weekly Gazette, 10 February 1902, p. 7.

Born in 1873 in Great Yarmouth, Norfolk, England, he had in 1894 succeeded Bennett Lang at the Royal Montreal Golf Club. Smith had apprenticed under George Fernie at Great Yarmouth in England and had won the position of greenkeeper at the Royal West Norfolk Golf Club in Brancaster, Norfolk, when it opened in 1892. He jointly held the course record that year on the new links course that he regarded as “the finest course to be found in England for first class golf” (Pittsburgh Weekly Gazette, 10 February 1902, p. 7). His subsequent application to Royal Montreal was the winning one from among the forty applications from Scotland and England that the club received (Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 8 November 1920 p 18). He became known as “a strong player” and as “a good groundskeeper” (Pittsburgh Weekly Gazette, 10 February 1902, p. 7)

At the urging of his brother Arthur, Smith left Montreal for the Westmoreland Country Club in Pennsylvania in the spring of 1902.

Within two years, he had moved to Pennsylvania’s Oakmont Country Club. He then accepted the position as golf instructor in Springfield, Ohio, until 1910, when he moved to Toledo, but he eventually returned to the Northeast via the Hackensack Golf Club, of New Jersey. He settled in Brooklyn, New York, working in the United States as a golf professional for the rest of his life (still employed late in his sixties), except for service in the Canadian Expeditionary Force during World War I, after which, when demobilized in the spring of 1919, he took up the position of golf professional at the Brantford Golf Club for a single season.

When Royal Montreal moved from Fletcher’s Field to its Dixie property in 1896, its new nine-hole course there was probably laid out by Simpson. And in the spring of 1898, he laid out a nine-hole golf course for an America summer resort on Lake Champlain. But when the Royal Montreal Golf Club decided to lay out an eighteen-hole championship course on its Dixie property in 1899, it was not Smith who has asked to design the new golf course, but rather Willie Dunn.

And so, had the Grand Hotel asked Royal Montreal for advice about who should be hired to lay out a golf course at Caledonia Springs, one presumes it would have recommended not its own Tom Smith, but rather the ubiquitous Willie Dunn.

Who was the Architect? Maybe

Figure 35 Willie Dunn, Jr, circa late 1890s.

My suspicion is that the first golf course at Caledonia Springs was laid out by Willie Dunn, Jr. He was the most prominent golf architect in North America in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

He was known in Ottawa even before the Ottawa Golf Club was founded in April of 1891, two years before Dunn came to the United States. When Hugh Renwick of Lanark, Scotland, helped to organize the Ottawa Golf Club in the spring of 1891, he recommended that the club invite Dunn to come to Ottawa to lay out a golf course and work thereafter as the club’s professional (Renwick played golf with Dunn at Biarritz, France, where Dunn was the golf professional). Club members did not follow Renwick’s advice, but they had learned from him a good deal about Dunn’s prowess as a golfer and as an architect and no doubt followed the news of his feats in America in the 1890s.

If the Grand Hotel Company’s managing director, Ottawa architect King Arnoldi, had asked Ottawa Golf Club directors for a recommendation regarding an architect, they might well have told him of Dunn.

Dunn was frequently in Canada in 1899 and 1900 – not just to lay out the new eighteen-hole championship course for Royal Montreal, but also to lay out many other nine-hole courses.

In the spring of 1899, Dunn visited Montreal to lay out a new eighteen-hole course for the Royal Montreal Golf Club: “Willie Dunn left for Montreal last night to superintend the new course of the Royal Montreal Golf Club, the oldest organization of the kind on the continent, it having been forced to lease new land, which it proposes to convert into a fine links” (Sun [New York], 26 April 1899, p. 9).

Dunn was in Dayton, Ohio, by 12 May 1899 to participate in the next day’s matches that officially inaugurated play on the course that he had earlier laid out. But he was back in the Thousand Islands in the summer. In July, we read in Kingston’s Daily Whig that “’Willie’ Dunn, New York, champion American golfer, was in the city Saturday. He left for Gananoque to lay out a links” (10 July 1899, p. 6).

Gananoque! Who knew?

Dunn was probably in the Thousand Islands area that spring to inspect his newly opened layout for the New Frontenac Hotel on Round Island, which, as we know, was very well received when the resort opened on June 20th . From Round Island, steamboats travelled twice a day to Gananoque, as well as to Kingston (the latter trip taking three hours).

It is possible that when Dunn was working in the Thousand Islands in the summer of 1899, he staked out a course at Caledonia Springs and that the construction and inauguration of the golf course was deferred until the opening of the 1900 season at the end of May.

Or the course may have been laid out and built in the spring of 1900. As we know, in those days, a golf course could be laid out and brought into play in less than two weeks.

Dunn was busy playing a great deal of golf in the early spring of 1900, practising extensively in advance of two matches scheduled against the reigning British Open champion, Harry Vardon. Since his victory in the first professional championship of the United states in 1894, Dunn had nursed his reputation as one of the best golfers in North America and had by this point ducked a number of challenges by other accomplished professionals lest he lose a match and harm his market value, but he could not duck a match against the touring Vardon.

On 31 March 1900, Dunn played a 36-hole match in Virginia against Harry Vardon, and the two played again in a 36-hole match on 10 April 1900 at Scarsdale Golf Club in New York. Dunn lost by sixteen holes in the one match and by seventeen holes in the other.

So, Dunn went off to lick his wounds on an extended trip laying out golf courses in northern New York State and the Thousand Islands.

In the third week of May, Dunn laid out a nine-hole course near Utica, New York, at Eagle Lake on Blue Mountain (Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 20 May 1900, p. 7). With nary a flat field in sight, he set 150 men at work blasting rock and filling ravines on the Blue Mountain slopes across which he had routed the holes. He collaborated on this project with Tom Bendelow (who was the golf professional of the public golf course at Van Cortland Park in New York City but who was also a golf course architect who claimed that by the turn of the century he had already laid out 150 golf courses):

On Eagle Lake, in a part of the Adirondacks until this year not readily accessible, the owner of a vast tract of land, with a liberal and thoughtful expenditure of time and money, has planned and had laid out, under the supervision of Willie Dunn and Tom Bendelow, a golf course, which for beauty of surroundings and excellence in itself is of special attractiveness. (Boston Evening Transcript, 11 July 1900, p. 6).

As was typical of the designs of the day, the greens were square: “The course is 3,033 yards, nine holes. The putting greens are of fine turf, 60 x 60” (Standard Union [Brooklyn, NY], 25 July 1900, p. 11). Dunn and Bendelow were unusually attentive to the ongoing work: “The Eagles Nest Club has undertaken to make a golf links in the Adirondacks that will rival any in the North Woods, and to this end both ‘Tom’ Bendelow and ‘Willie’ Dunn have been making frequent trips there to superintend the construction” (New York Tribune, 12 July 1900, p. 6).

Dunn seems to have used Utica as a base for trips north to the border. He played a match in the Utica area on May 19th, and we read on May 20th that Dunn was heading north next: “Dunn now goes to the Thousand Islands where he will lay out three different courses” (Sun [New York], 20 May 1900, p. 10).

In fact, as the Philadelphia Inquirer reported, Dunn laid out more than three courses:

The Thousand Islands is the latest centre of golf.

The proprietors of the isolated manors are breaking their fishing rods into golf clubs and bending the boat hooks into putters.

Willie Dunn laid out a score of links on a number of islands, and now George Low has laid out a course on Well’s Island, this being the property of Mr. George Boldt, who has also become an enthusiast of the game. (27 May 1900, p. 13)

One of the score of courses in the “Thousand Islands” that Dunn laid out may well have been the one on Stanley Island, where, like the Grand Hotel at Caledonia Springs, the Algonquin Hotel began advertising its golf course in June of 1900.

Dunn’s trip north to Canada may have been of about two weeks’ duration, for we read that he was back in Utica on 4 June 1900 to play an exhibition match against local players (Sun [New York], 8 June 1900, p. 4).

Dunn probably included a visit to Montreal on this trip, for the Royal Montreal Golf Club had twelve holes of the new Dunn course ready for play by the beginning of the 1900 golf season but planned to complete the remaining six holes by the end of the summer. This 18-hole project in Montreal was even bigger than the 9-hole Adirondacks project where Dunn was regularly on site, so it seems likely that he would have checked on how things were going in Montreal.

Was Caledonia Springs another of Dunn’s stops?

Several trains ran daily between Montreal and Caledonia Springs. Dunn might well have gone out to the Grand Hotel on a morning train and returned to Montreal the same day on an evening train.

A Dunn-Style Golf Course

By the mid-1890s, Willie Dunn had become the most famous North American exponent of “penal design theory.”

In 1898, in the chapter called “The Making and Keeping of Golf Courses” in his 1898 book, The World of Golf, Garden Smith explains the philosophy behind penal design:

As a general principle, at every hole, except on the putting green where it brings its own reward, a bad shot should be followed by a bad lie, and a good shot should be correspondingly rewarded by a good one.

Now it is impossible, at every hole, to provide a fitting punishment for every kind of bad shot…. But there is one kind of bad stroke which by universal consent must be summarily punished, whenever and wherever it is perpetrated, and that is a “topped shot.”

The reasons for this are obvious. The shot has been missed and missed badly, but on hard ground or against a wind, a topped ball will sometimes run as far, or even further, than a clean hit one, and the player will suffer no disadvantage from his mistake.

Wherefore, in making your first tee, select a spot some sixty yards in front of which a yawing bunker stretches right across the course, and if it be so narrow, or so shallow, that a topped ball will jump over it, dig it wider and deeper, so that balls crossing its jaws will inevitably be swallowed up. (The World of Golf [London: A.D. Innis & Co., 1898], pp. 87-88)

One can see that according to this architectural theory, inveterate duffers were to experience just punishment for their ineptitude at least once on every hole.

Penal design theory had been popularized in Britain in the late 1880s and throughout the 1890s by the golf course designs of Willie’s older brother Tom, under whom Willie had apprenticed at North Berwick in the early 1880s. Tom Dunn – and, in turn, his brother Willie, as well as several of their nephews – became particularly notorious for a certain style of earth-bank bunkering laid out transversely across the entire width of fairways: these obstacles came to be called “cross-bunkers.”

Although Tom Dunn may not have been the only architect to use cross-bunkers spanning the entire width of fairways, he “is believed to [have been] the first to use turf dikes (dug-up earth piled high to form a wall) …., occasionally placing sand at the base” (Forrest L. Richardson and Mark K. Fine Bunkers, Pits & Other Hazards [Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley, 2006], p. 104).

There were often two sets of earth-banked cross-bunkers per two-shot hole:

Tom Dunn's courses were rudimentary given the lack of earth moving equipment available at that time.

His standard design feature was to lay out a ditch or bunker on the near side of the green, often right across the course, which had to be carried from the tee.

It was the same kind of carry for the second shot, and if the player had to hack out of the first bunker, the next hazard was in reach. (Famous North Berwick Golfers http://www.northberwick.org.uk/dunn.html).

Golf historians suggest that the rudimentary earth-banked cross-bunker hazards for which Tom Dunn became famous – and for which he subsequently became infamous when they went out of fashion – were the simplest and most economical way for him to introduce hazards onto the otherwise featureless land where he was asked to build most of his golf courses.

Figure 36 Tom Dunn (1849-1902), circa 1900.

Because Tom Dunn was the leading figure in the late 1800s’ movement to build golf courses near the big cities in the south of England – building them, consequently, not on the traditional golf course sites (the seaside links land that was generally remote from cities) but rather on inland sites such as heaths, parks, commons, pasturelands, croplands, and so on – his style of “earth-bank” or “turf-dike” bunkering became ubiquitous.

In the late 1880s, Tom and Willie had together laid out what became a very famous eighteen-hole championship course in Biarritz, France, where Willie served as the resident golf professional until he was lured to Shinnecock Hills in Southampton, New York, in 1893.

And at Shinnecock Hills, Willie Dunn immediately added six holes to the twelve holes that had been laid out by the Royal Montreal Golf Club’s professional Willie Davis in the summer of 1891. (Davis had laid out the twelve-hole links of the Ottawa Golf Club in the spring of 1891 before going to New York to lay out the course at Shinnecock Hills.)

As the USGA explains in “The Evolution of Shinnecock Hills Golf Course,” Davis and Dunn between them laid out a course absolutely in accord with penal design principles:

The Davis/Dunn course … reflected the architecture then prevalent on late Victorian English inland courses. The course’s mostly straight holes were traversed by cross hazards in the form of “cop” bunkers, ravines, ditches, roads, rail lines or other obstacles.

Following Victorian design tenets, such hazards were placed so that players were required to hit over them and for that reason they were often called “carry” hazards. They could be quite severe, on the rationale that the worst miss – the dreaded topped shot – deserved the most severe punishment.

Typical of courses of the period, Shinnecock’s cross hazards were set at prescribed distances from tees or greens …. that were often flat, square and largely without bunkering.

In North America, Willie began designing golf courses with earth-banked bunkers within months of his arrival at Shinnecock Hills. Among the earliest of his bunkers of this sort were those constructed in the fall of 1893 on the otherwise featureless land of the Golf Club of Lakewood, New Jersey. Three of Dunn’s crude earth-bank bunkers at Lakewood are seen in the photograph below

Figure 37 Earth-bank bunkers that Willie Dunn, Jr, designed for the Golf Club of Lakewood, New Jersey, in 1893.

At Round Island, Dunn had been blessed with many natural hazards: ranging from gullies to large areas of exposed sand. And so, he had routed as many of his golf holes as possible across these hazards in order to force golfers to hit the ball over them in the air to avoid loss of strokes:

“The Cliff” [the fourth hole] is the sportiest hole in the course. A good drive clears the bunker ….

The tee for the sixth hole [“The Landing”] is prettily perched on the crest of a ledge, and favors a clean, long drive to the green 200 yards away. A topped ball will, however, land in a sand gully ….

[On the 304-yard eighth hole, called “Over the Hill,”] A long sandy rise stretches out from the tee for nearly a hundred yards, but from the top a good turf runs level to the green. (Golf [September 1899], vol 5 no 3, pp. 196-97, emphasis added to highlight the carries required)

Still, even at Round Island, Dunn had to use his distinctive artificial bunkers in areas where there were no natural hazards: “The hazards are natural, save for four picturesque bunkers, through the more open green [i.e. fairways]” (Golf [September 1899], vol 5 no 3, p. 196).

Not everyone agreed that Dunn’s earth-banked bunkers were “picturesque.”

Dunn apparently added one of his fairway-wide cross-bunkers on the final hole: “The home hole, ‘The 400,’ is the longest (401 yards) and prettiest of the course, lying straightway over a level turf, with only a cluster of spherical bunkers and a transverse [bunker] of sand to prove at all troublesome” (Golf [September 1899], vol 5 no 3, p. 198). The “tranverse” bunker was the Dunn family signature.

As we know, in 1899, around the same time that Dunn laid out the nine-hole golf course on Round Island for the New Frontenac Hotel, he also laid out an 18-hole course for the Royal Montreal Golf Club. Here, we find the same determined routing of golf holes across fairway-wide hazards, each of which will have to be carried by a shot through the air if the golfer is not to lose strokes:

The Sidey Hole, No. 1. 395 yards, A good straight drive … will enable a long brassey to carry the ditch….

The Highway Hole, No. 2. 235 yards. A moderate drive will just reach the ditch ….

The Kopje Hole, No. 3. 150 yards. A short drive is punished by bunker and sand….

The Lower Brook, 400 yards. A good drive must be made to enable brassey to carry the railway….

Figure 38 The putting green of "The Lower Brook" of the Royal Montreal Golf Club. Golf, vol 9 no 5 (November 1901), p. 346. Note the stone wall beyond the green. Stone walls had to be carried on several holes.

[Because of an error in its typesetting, the Montreal Star accidentally omits descriptions of the 180-yard par-three fifth hole, called “The Upper Brook,” as well as the 125-yard par-three sixth hole, called “The Corner.”

Fortunately, however, we know from accounts of the match that Harry Vardon played in September of 1900 against the best ball of Royal Montreal professional Tom Smith and Toronto Golf Club professional George Cumming that the latter hole involved crossing a substantial water hazard, for although Vardon and Smith carried it, Cumming did not.

We can see in the photograph below a view across the water towards the teeing ground of “The Corner,” where a caddie departs from this tee on the left side of the photo.]

Figure 39 The tee on "The Corner" at the Royal Montreal Golf Club. Golf, vol 9 no 5 (November 1901), p. 348. Note the railway tracksin the background, over which Dunn routed at least two of the golf holes.

[A good drive on No. 7, the 342-yard par four known as “The Elm Tree Hole,”] will enable cleek shot to carry bunker and reach the green.

The Meadow Hole, No. 8. 370 yards. The drive must carry bunker; the brassey, unless very long, may reach sand bunker guarding green ….

The Hawthorn Hole, No. 9. 100 yards. A well played mashie shot will drop on the green, which is guarded by the brook on the near, far and right sides.

The Spring Hole, No. 10. 250 yards. A good drive diagonally across the brook will give a mashie shot over stone wall into the hollow of the green.

The Plum Lane Hole, No. 11. 377 yards. The drive must carry the railway ….

The Home Hole, No. 12. 240 yards. The drive must carry bunker and avoid road to left. (Montreal Star, 22 September 1900, p. 18).

Almost every hole required the golfer to carry at least one shot over a fairway-wide hazard or to play a shot carefully short of a hazard.

What hazards would Dunn, or any other architect, have had at his disposal for a penal layout over the Grand Hotel Company’s property?

The Golf Grounds of the Grand Hotel

Recall that according to the description provided in the brochure of 1899, the land around the hotel was relatively flat and deforested:

The property of the Company comprises about 200 acres; a grove occupies about 30 acres, and the enclosure around the Grand Hotel about 25 acres. In the latter is the Post Office, Protestant and Catholic churches, etc…. The Baths are in the main building of the Grand Hotel; the Gas, Saline and White Sulphur Springs immediately in front…. The site of Caledonia Springs is in the midst of an elevated plateau; the country generally has been well cleared and is almost devoid of bush or trees, except such as are preserved in the immediate vicinity for ornamental purposes…. The drainage of the grounds, together with the clearing up of the surrounding country, has practically banished the mosquito… (Magi Caledonia Springs brochure 1899, pp 5-7)

From the point of view of any golf architect in 1900, there were two important geographical features of the Grand Hotel’s land not mentioned in the brochure: first, several branches of the Ruisseau des Atocas wound through the hotel’s property; second, the springs that were located “immediately in front” of the hotel were at the bottom of a fairly wide and deep gully.

Figure 40 William Parker, The History Rise and Progress of the Caledonia Springs, Canada West (Montreal: James Starke, 1844).

This gully, with steps leading down to the bottom of it, can be seen in the earliest images of the resort at Caledonia Springs (as shown in the sketch from 1844 to the left).

The same gulley (along with what may be the same two-storey pavilion from 1844 at the bottom of it) can be seen in a mid-1870s photograph of the new Caledonia Springs hotel built by King Arnoldi.

Figure 41 Photograph dated 1875. Library and Archives Canada.

By the early 1900s, plaster was falling from the second-floor ceiling of the pavilion, but this building at the bottom of the gully where springs were located clearly remained a focus of guests’ interests.

Figure 42 Guests crowd the pavilion in front of the Caledonia Springs Hotel in the early 1900s.

Whether the golf course of 1900 was laid out by Dunn himself or by another North American golf professional (who would inevitably have subscribed to the tenets of the penal design philosophy that the Dunn family popularized), we can be certain that one or more of the golf holes of the 1900 course would have been routed across this natural hazard, and others might have been routed alongside it so that the gully served as a penalty for wayward shots played left or right of the intended line.

Reproduced below is a detail from a topographic map of the Caledonia Springs area drawn up in the early 1900s and published in 1909.

Figure 43 Enhanced and annotated detail from 1909 topographic map.

The map shows the Grand Hotel (as an “H” highlighted within a yellow circle) in its location on the east side of the Leduc Side Road south of the village. It also shows the two churches, the Post Office and the 30-acre grove within the hotel’s grounds as these grounds are described in the excerpt above from the hotel’s 1899 brochure. (The other hotel marked with an “H” on the map above is the Queen’s Hotel, which was found guilty in the early 1900s of infringing on the Grand Hotel Company’s copyrighted names for the local spring waters). I have marked with orange arrows both the north-east perspective of the first photograph below (which looks from the hotel roof toward the village) and the south-west perspective of the second photograph below (which looks from the hotel roof across the fields and grove on the other side of the hotel).

Figure 44 View northeast from the roof of the Grand Hotel. Handbook to Caledonia Springs for 1896.

The view in the photograph below is 180 degrees opposite to the view in the photograph above.

Figure 45 The view southwest from the roof of the Grand Hotel. Handbook to Caledonia Springs for 1896.

All the golf courses built at Caledonia Springs were said to have been laid out close to the hotel.

And so, as we shall see, the photographs above (taken in 1896) provide a view of the locations of at least four of the golf holes to be laid out in the near future.

The Short Life of the First Golf Course

As noted above, the first reference to golf at Caledonia Springs was made by the Grand Hotel in an announcement published on 21 May 1900: “All amusements usual at summer resorts are found at Caledonia Springs. With the opening of the season a golf club is to be formed from among the visitors and the new links inaugurated” (Gazette [Montreal], 21 May 1900, p. 4).

Since it was also announced that the “Season of 1900 opens May 30th,” we know that the golf course was supposed to be ready for play at the end of May (Gazette [Montreal], 21 May 1900, p. 4).

That Dunn’s visit to Canada in 1900 began on the 20th or 21st of May, on the one hand, and that the Grand Hotel announced at the same time that it would form a golf club and “inaugurate” a golf course ten days later, on the other hand, may be no coincidence. If Dunn had begun his work in Canada by going to Montreal first, he would have found that there was daily train service from Montreal to Caledonia Springs and so could have planned for his work at Caledonia Springs to take a single day.

That hotel management might have presumed that the course could be opened for play within about ten days of Dunn’s visit would not have been surprising. In the spring of 1903, for instance, the Victoria Golf and Country Club of Montreal announced on April 22nd that it had “made arrangements to have Mr. Thos. Bendelow … come to Montreal and go over their property at St. Lambert for the purpose of conferring with [Peter] Hendry, the club professional, as to the best plan for the new links…. The links will be open to the members on May 1st” (Gazette [Montreal], 23 April 1903, p. 2). It turns out that Bendelow was not able to visit the Victoria Golf Club until the fall, but the club’s expectation that golf would be possible on a new layout ten days after it had been staked out by Dunn is instructive.

There was no more mention of Caledonia Springs golf in the newspapers until August, when the following advertisement ran in Ottawa and Montreal newspapers from August 10th to August 17th: “Essentially a health resort with superior accommodation, golf, and concomitants of the popular spa, Magi Caledonia Springs … is the delight of holiday seekers” (Montreal Star, 14 August 1900, p. 4).

Perhaps, after declaring that a golf club would be formed and the new links inaugurated on May 31st , the hotel was silent about golf in June and July because hotel management had underestimated how long it would take to build the golf course and get it into playing condition.

Advertisements in 1901 began to promote the hotel’s golf facilities in mid-June: “The air, company, accommodation, waters, and baths of Caledonia Springs are unique health factors – golf … Write for Guide” (Ottawa Journal, 24 June 1901, p. 4). This advertisement ran for three weeks until the end of the first week of July.

School was to start earlier than usual in September of 1901, so the Grand Hotel used the prospect of a relatively child-free environment at the hotel to encourage golfers to patronize the resort that month:

Caledonia Springs, Ont.

The early re-opening of the schools is having its effect here in the character of the visitors which comprise now mainly those seeking the health giving qualities of the waters. The invalid, however, is not over prominent, so many being accompanied by relatives of friends of undoubted health.

The intention is to prolong the season to the 18th of September.

The golf links have been steadily improved and may now be classed as among the best in Canada. (Daily Whig [Kingston, Ontario], 31 August 1901, p. 4)

The same report appeared verbatim three days later in the Ottawa Citizen, perhaps suggesting that we have here a press release from the Grand Hotel Company (Ottawa Citizen, 2 September 1901, p. 5). And so, one might take with a grain of salt this claim that the Grand Hotel now had one of the best golf courses in Canada: it smacks of the sort of self-aggrandizing exaggeration that a summer resort might use in its self-promoting advertisements.

Note that in 1902 there are no more references to its golf course in any of the newspaper advertisements run by the Grand Hotel. Its advertisements continue to celebrate recreations available on the grounds, but not golf: “Surrounding the Grand Hotel is a judiciously planted park of about thirty acres – the private grounds of the property – with walks, croquet, quoit and tennis lawns” (Gazette [Montreal], 3 June 1902, p. 4).

Why such silence about one of Canada’s “best” golf courses?

When we learn in 1903 that the hotel has been sold, and that the new owners of the resort immediately announced that a new golf course would be built, we can assume that the golf course laid out in 1900 and touted as “among the best in Canada” in 1901 was not quite what it was cracked up to be.

In 1904, newspaper references to the new golf course built that spring perhaps provide information retrospectively about the original golf course of 1900. In June of 1904, newspaper items about the Caledonia Springs Hotel, on the one hand, and the newspaper advertisements placed by the hotel itself, on the other, assured potential guests that the “nine-hole golf course … is in charge of a competent golfist” (Montreal Star, 27 June 1904, p. 6). The “golfist” in question – that is, the greenkeeper or golf professional (the roles were usually combined in the same person in the late 1800s and early 1900s) – is not identified, but his competence is emphasized again the next month in a reference to “A well laid out nine-hole Golf course, close to the hotel, in charge of a competent man” (Gazette [Montreal], 18 July 1904, p. 4).

In light of these repeated assurances that there was a competent man in charge of the new links at Caledonia Springs, one might suspect that the new owners of the hotel were addressing a problem that affected the reputation of the original golf course: perhaps it had not been maintained by a golfist at all, let alone a competent one. That the golf course had been “steadily improved” between 1900 and 1901 may have been a result not of a greenkeeper’s programme of planned improvements but rather of continual complaints about golf course deficiencies. Emphasis on the new man’s competence was perhaps intended to put paid to problems with the nature and condition of the course that had beset the hotel’s first venture into golf.

Hotel guests who usually played their golf at the Chelsea Links of the Ottawa Golf Club or on the golf courses of the Montreal clubs perhaps informed management of the Grand Hotel that its golf course was so far from being “among the best in Canada” that it did not even pass muster. There is a suggestion that hotel management had become aware of the golfing public’s increasing expectations regarding resort golf courses in a hotel advertisement’s reference to the new course of 1904 as “new and interesting” (Montreal Gazette, 31 May 1904, p. 10, emphasis added). Had the original course been criticized as uninteresting? Similarly, a newspaper item that probably emerged from information supplied by the hotel indicated that the golf course had been designed “in order to meet the wishes and the wants of the devotees of that popular and fashionable game” (Ottawa Citizen, 3 June 1904, p. 3). Again, the hotel shows an awareness of what a golf-playing guest “wishes and … wants” to find in a resort golf course.

Note also that the New Frontenac Hotel had since 1898 employed both a greenkeeper (from the Cleveland Golf Club) and an experienced maker and repairer of golf clubs. Perhaps references to the “golfist” at Caledonia Springs were also designed to show that the hotel at Caledonia Springs was keeping up with the other resorts in terms of addressing the golfing guest’s increasing expectations regarding the services that would be available at resort golf facilities.

The 1904 Layout

The Grand Hotel and its property was acquired by new owners during the 1903 season and so the hotel was completely renovated during the following winter. It reopened during the first week of June in 1904: “the hotel is now made fully up-to-date in conveniences and character …. Besides other facilities for amusement and pleasure of the guests, a golf course has been laid out by an expert, which should surely add largely to the attractiveness of this well and favorably known health resort” (Ottawa Journal, 4 June 1904, p. 19)

A golf course had been part of the new owners’ plans from the beginning. Late in the summer of 1903, they sent an architect on “a tour of leading mineral springs resorts in the States” for “pointers on hotel construction with a view to preparing plans for the elaborate scheme of the new proprietors of Caledonia Springs” – a scheme that included a plan “to lay out a race course adjacent to [the hotel], with golf and tennis grounds” (Gazette [Montreal], 26 September 1903, p. 2).

The new golf course was indeed “laid out by an expert.”

Figure 46 Charlesa Murray, 1902. Photograph copyright Canadian Golf Hall of Fame.

We read in the spring of 1904 that “A new and interesting Golf Course has been laid out by C.R. Murray, the well-known professional of the Westmount Golf Club” (Montreal Gazette, 31 May 1904, p. 10).

That the leader of the syndicate that took over the Grand Hotel, promoter David Russell of Montreal, commissioned Murray to lay out the golf course shows that the new proprietors were serious about providing guests with a proper golf experience.

Charles Richard Murray had been born in Birmingham, England, in 1882, but when he was six years old, his family immigrated to Canada, taking up residence in East Toronto near the Toronto Golf Club. Murray, like many young boys in his neighbourhood, caddied at the club and became proficient at the game. When George Cumming became the golf professional in the spring of 1900, he chose the best among these caddies to become his apprentices: Murray was the foremost among them. By 1902, he was ready for his first appointment as a golf professional: he was hired by the Toronto Hunt Club. In 1903, he became the golf professional at the Westmount Golf Club of Montreal. (Two years later, he became the head pro at Royal Montreal, where he worked until his death in 1939.)

Murray had been trained in the art of laying out golf courses by his mentor George Cumming. From greenkeeper Frew Hawkins’ account of Cumming’s laying out of a nine-hole extension to a golf course in 1906, we can glean insight into how Murray had been taught to lay out golf holes:

Figure 47 George Cumming, 1879-1950.