CONTENTS

Foreword

Acknowledgements

Preface

Introduction

A Word on the Organization of the Book as Four Volumes

Volume One: The Course of Fred Rickwood’s Life: From Ilkley to Orillia

Early Life and Golf Apprenticeship

Harry Vardon’s Apprentices

Little Fred’s Little “Z”

First Soldiering

First Canadian Golf: Toronto

Amherst

Maritimes Open

Quebec

Saint John

Second Soldiering

Digby

Returning to Ontario Golf

The Summit Club and Stanley Thompson

Working with Stanley Thompson

Bentgrass Guru

Rickwood’s Apprentices

Fred Rickwood’s Golf Game

The Thornhill Golf Club and More Work with Thompson

Simultaneously Golf Professional and Architect

A Unique and Clever Partnership with Billy Brazier

Billy Brazier

Napanee and the Partners Hook-Up

Between Belleville and Saugeen

Rickwood’s Prospects Post-Napanee

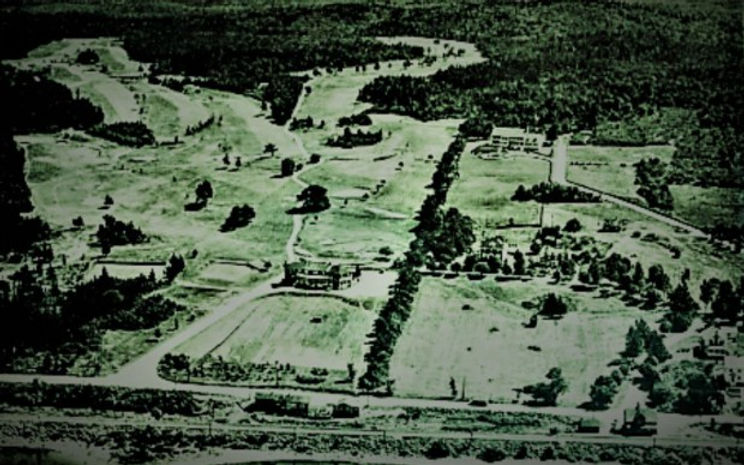

The Couchiching Golf and Country Club

Parry Sound

Cutten Fields

A Biographical Postscript

Appendix 1: Golf Courses Laid Out, Remodelled, or Constructed by Fred Rickwood

Appendix 2: Fred Rickwood’s “Iron Man” Fan

Foreword

This book remains a work in progress.

I circulated the first edition among members, friends, and supporters of the Napanee Golf and Country

Club.

I did so first and foremost because it is about something we all love: the Napanee golf course.

But I also wanted to invite people who read this book and find the subject interesting to ask themselves whether they might have a piece of information about the Napanee golf course – a fact, an anecdote, a rumour, a photograph of some part of the golf course, an old publication from the club, or even an old scorecard--that they could pass along to me. Information about the golf course that lies in the background of a photograph, for instance, even if it is only a photograph of a trophy presentation or of a group of friends playing golf, or information that emerges from a story about the past, may help to fill out the picture of the history of the designing of the golf course that I sketch below.

The second edition of the first volume of this book is archived at the Orillia Public Library. So I similarly invite anyone from Orillia (where Fred Rickwood was the head professional golfer at the Couchiching Golf Club from 1928 to the early 1930s) who might have information about him to pass it along to me. People able and willing to share memories of him will contribute to the remembering that he deserves.

Feel free to email me:

dchilds@uottawa.ca

More information about either the Napanee golf course or the man who designed it will make for a better third edition.

Donald J. Childs

Acknowledgements

My brother Bob Childs has done wonders with computer technology on my behalf, especially with regard to old photographs. His love of Napanee Golf and Country Club probably exceeds my own, and it certainly inspired me in my work on this book.

Milt Rose’s enthusiasm for the history of the golf course, particularly as shown by his willingness to listen to my recitation of facts and figures that emerged as I first worked on this book, was also an encouragement to me.

Napanee Golf and Country Club’s Golf Course Superintendent Paul Wilson has generously provided me with helpful information that he has gathered from his work on the course over the years.

I appreciated Rick Gerow’s willingness to tell me about the construction of various parts of the golf course in the 1980s and 1990s, even though we were playing golf at the time and he was in the process of winning the Super Senior Golf Championship.

Similarly, Bing Sanford cheerfully and helpfully identified features of the Rickwood course for me when we played a round of golf together. It was always a pleasure to be in his company.

Mike Stockfish read an early draft of the book and offered encouragement and useful advice, for which I thank him.

When I requested information from the Orillia Public Library about an item on Fred Rickwood, the response of Amy Lambertsen, who runs the library’s Local History Room, was immediate, helpful, and generous. What a wonderful librarian!

Lisa Lawlis, Archivist at the County of Lennox and Addington Museum and Archives, was thoroughly efficient, encouraging, and supportive through all the many hours of her time that I monopolized. What a wonderful archivist!

Jane Lovell, a member of the Adolphustown-Fredericksburgh Heritage Society, researches and writes about local history. She has a special interest in the Herrington family and Camp Le Nid and generously corrected errors in and contributed information to the second and third volumes of this book. Jane works tirelessly in promoting the preservation of local history and the dissemination of knowledge about it. I am very appreciative of her contributions to this project.

Margaret McLaren, a golf historian with a main focus on the Rivermead Golf Club, kindly informed me of Fred Rickwood’s work at the Belleville Golf Club and supplied newspaper clippings about it. I thank her for this important contribution.

I thank Sandy Gougeon, a granddaughter of Bill Brazier, for kindly correcting several inaccuracies in my account of Brazier’s life and for helpfully supplying further information about and photographs of her grandfather.

I also thank Karen Hewson, Executive Director of the Stanley Thompson Society, and Lorne Rubenstein, Canadian golf journalist and golf writer without peer, for encouraging words in support of my research on Fred Rickwood.

Dr. T.J. Childs was extraordinarily helpful in discovering information, documents, and photographs about a large number of the people whose stories are highlighted in this book. His genealogical skills are extraordinary.

Vera Childs donated funds to provide access to important rare photographs that were essential to my telling of the story of the earliest development of golf in Napanee. I thank her for her generous support of this project.

I am grateful to Janet Childs for her patience and forbearance during my work researching and writing this book, and I am especially grateful for her hard work in preparing this book for publication.

Perhaps most important to a book like this, however, is the pioneering work on the collection and interpretation of local archival information about the golf course by Art and Cathy Hunter, and their band of fellow researchers, published as Golf in Napanee: A History from 1897 (2010). To contribute to what they started is a pleasure and a privilege.

Preface

If you Google the name “Fred Rickwood,” your search will yield little beyond the fact that he participated in a number of Canadian Open and Canadian PGA golf championships in the first quarter of the twentieth century.

The search might also reveal an image of his grave marker in Toronto’s Prospect Cemetery.

Figure 1 Fred Rickwood grave marker, Prospect Cemetery, St Clair Avenue, Toronto.

The gravestone tells us little about Fred Rickwood. Apart from his name, date of death, and age, he is identified only as Company Quarter Master Sergeant Fred Rickwood of the 26th Battalion of the Canadian Expeditionary Force.

So much is missing.

There is not even a date of birth, and so perhaps it is not surprising that the age given is wrong.

Most importantly, there is nothing about his life in Canadian golf, which is a great shame, for golf was the main reason for his Canadian life.

This book is an attempt to honour Fred Rickwood by remembering his life in early Canadian golf, particularly with reference to his design of the Napanee golf course.

The greatest legacies that golf course architects leave golfers are their golf courses – the ones that endure as times change and continue to engage the interest of golfers as each new golfing generation emerges. In Nova Scotia and Ontario, several of Rickwood’s golf courses remain in play, hosting many thousands of rounds of golf each year. The oldest of his golf courses is 110 years old; the youngest, a spritely ninety.

Long may Fred Rickwood’s legacy golf courses last – especially that of the Napanee Golf and Country Club!

Introduction

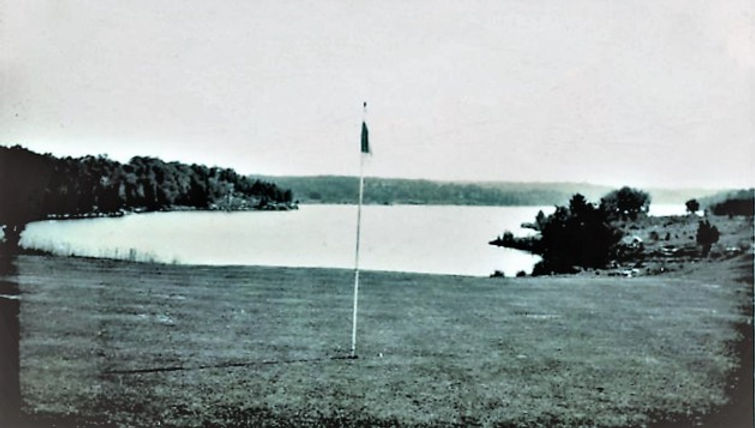

In an article celebrating Napanee Golf and Country Club’s emergence into a third century since its opening in 1897, Flagstick magazine observes that “There is no designer of record for Napanee. Much like the historic courses of the United Kingdom, its nine holes (but ten greens and with eighteen separate tee locations) were crafted gradually – with renovations taken upon by the membership when it has been deemed necessary” (8 June 2007).

To say that there is no designer of record for the Napanee golf course is true enough, as far as it goes. Yet the absence of a designer of record is not a matter of a missing designer, but rather a matter of missing records. Or more accurately yet, it is a matter of not inspecting the existing records closely enough.

For closer inspection of the records reveals that there was indeed an identifiable designer of the Napanee Golf and Country Club’s course, that his work dates from what is known as “the Golden Age” of North American golf course design, and that his golf course design mentor was the greatest of all Canadian golf course architects: the legendary Stanley Thompson.

In Golf in Napanee: A History from 1897 (2010), Art and Cathy Hunter reproduce two 1927 articles from local newspapers that draw attention to a visit to the Napanee Golf and Country Club that summer by a pair of golf professionals, one of whom would exert a fundamental and continuing influence on the playing of golf in Napanee.

The Hunters draw attention to the following item in the Napanee Beaver(10 June 1927):

GOLF MATCH

The match played here Wednesday afternoon was a very interesting game and was followed by a large crowd of spectators. Bill Brazier, British Professional of Toronto, was paired with George Faulkner, a young amateur from Belleville Country Club, against Fred Rickwood, British Professional of Toronto, and W. Kerr, Professional at the Cataraqui Golf Club. On the first round Brazier and Faulkner were two up and held the same lead during the second round. Brazier made a score of 76, for the 18 holes, which is good, considering that the greens are not in a fit condition for putting. He plays a very steady game and seldom got in any difficulty. His partner, George Faulkner, got in trouble several times on the first round, but played a 39 in the second round and if he continues, he should soon be heard of in the Canadian Championship matches.

Rickwood had 40 for each round and had three penalties. He played a very sporting game and took chances rather than playing safe, which of course pleased the spectators. He made some great recoveries after getting in difficulties. Kerr could not seem to get going in the first round, and the course did not seem to be to his liking, taking a 47 the first round. However, he improved in the second round and made a 39. Final scores, Brazier 76, Faulkner 84, Rickwood 80, and Kerr 86. After the game Brazier gave a very excellent demonstration of how a ball should be driven with the different kinds of iron and wooden clubs and apparently could make the ball do anything he wished. Both Messrs. Brazier and Rickwood have been very busy giving lessons to the local members, and all are delighted with their work. Brazier's two lectures have been most instructive to golfers. Rickwood, besides being a good instructor, is an expert in laying out courses and building greens, and has during his stay, laid out a new green and practically completed it.

The Management of the Club were very fortunate in securing their services, and it is to be hoped they will return in the near future, as there are many who have not had the chance to obtain lessons from them.

The Hunters also note the following piece a few days later in The Napanee Express(14 June 1927):

GOLF WEEK

Last week the Napanee Golf and Country Club staged an interesting and profitable week for its members. Messrs. Bill Brazier and Fred Rickwood, two well-known professional golfers, spent the week at the course, giving lessons to those asking for them, and repairing and selling clubs and advising the members on any golf matters at request. On Monday Mr. Brazier, who is a wonderfully fine golfer and a splendid teacher, gave a lecture on wooden clubs, and on Wednesday evening an exceedingly interesting lecture on iron clubs. On Wednesday afternoon Messrs. Faulkner, of Belleville, and Kerr, of Kingston, played an exhibition game with Messrs. Brazier and Rickwood. Eighteen holes were played, … Brazier and Faulkner ... winning the match. The golfers who attended the game were treated to a fine exhibition…. Mr. Rickwood, who has had years of experience in laying out golf courses, has prepared a plan for the improvement of

the Napanee course, and while here laid out and completed a new number one green. Messrs. Brazier and Rickwood will return here in August to lay out further improvements in the course. Both gentlemen were delighted with the Napanee course, stating that the fairways were the best in Ontario, and with improvement to the greens the course will be one of the very best nine-hole courses in Ontario. A large number of the Napanee enthusiasts received instruction from the professionals, keeping their time fully occupied during their stay.

Who was this Fred Rickwood? Who was this Bill Brazier? And how did they come to be barnstorming the province on a fix-your-swing, fix-your-clubs, fix-your-course mission?

In particular, what can we learn about this “course-whisperer” Fred Rickwood and how he had accumulated “years of experience in laying out golf courses”? What might it have been in his “years of experience” that led the management of the Napanee Golf and Country Club to commission him, rather than another golf course architect, to present plans for the improvement of its golf course?

We note that the one newspaper indicates on June 10th that it was “to be hoped they will return in the near future,” whereas just four days later we read in the other newspaper that “they will return here in August to lay out further improvements in the course.”

Their return was to be in the very near future, indeed! And their plans for that return went from vague to certain in just four days. Their June visit must have impressed the golf club. What was it that convinced club management to let course designer Fred Rickwood lay out a new and improved course that August?

These questions are important for lovers of the Napanee Golf and Country Club, for the present routing of the golf course is largely due to his work late in the summer and early in the fall of 1927. Five of his 1927 greens are still used at the Napanee golf course, and on holes where his original greens have been replaced, his fairways and tee boxes are still in use.

So here is our missing designer of record: Fred Rickwood.

A Word on the Organization of the Book as Four Volumes

This book, A Forgotten Life in Canadian Golf: Remembering Fred Rickwood and the Making of the Napanee Golf Course, is presented in four volumes.

Volume One, The Course of Fred Rickwood’s Life: From Ilkley to Orillia, presents the biography of this Canadian golf pioneer.

Volume Two, Napanee Golfers and their Courses to 1906, provides biographies of the earliest known golfers in Napanee, discusses the golfing grounds where golf was first played in the area, and discusses the first golf course laid out in 1897 and used down to 1906.

Volume Three, The 1907 New Course and Four of Its Players, discusses the first nine-hole golf course laid out for the Napanee Golf Club, presents photographs of the 1907 design, and presents biographies of the four golfers who appear in the photographs in question.

Volume Four, Blending Penal and Strategic Design at Napanee, reviews the architectural principles that Rickwood learned from mentors like Stanley Thompson and analyzes in Rickwood’s design practices at Napanee his implementation of principles associated with the 1910-37 period of golf course construction that Geoff Shackleford calls The Golden Age of Golf Design (Sleeping Bear Press 1999).

Volume One: The Course of Fred Rickwood's Life: From Ilkley to Orillia

Early Life and Golf Apprenticeship

The Amherst Golf Club in Nova Scotia where Fred Rickwood did his first work as a golf professional in 1908 indicates on its website that Fred Rickwood “worked for many years with the famous Harry Vardon in England.”

One presumes that when Fred Rickwood applied to the Amherst Golf Club to serve as its professional golfer, he was armed with a letter of reference (or what an Englishman like him would have called a “testimonial”) from Vardon himself – golf’s first international superstar in the late 1800s and early 1900s, the winner of six British Open championships and one US Open championship. Today, the “Vardon Grip” (that is, the Vardon way of gripping the golf club) is still used by as many as 70% of the world’s golfers and the PGA Tour in the United States awards the Vardon Trophy to the player with the lowest scoring average over the course of a season.

Figure 2 Harry Vardon circa 1890s.

We might surmise that Fred Rickwood served his apprenticeship under Harry Vardon at some point while the latter was employed from 1896 to 1902 as the professional golfer for Scarborough Golf Club, Yorkshire, which was located in those days at the Ganton golf course (during this period Vardon won three of his British Open championships), for Rickwood was born and raised in Yorkshire in the 1880s and 1890s and lived less than a mile from where Harry Vardon’s brother Tom was the golf professional at the Ilkley golf course.

It was to his brother’s golf course in Rickwood’s home town of Ilkley that Harry Vardon came to play in 1893 in order to compete in his brother’s golf tournament which had been organized to help popularize the game amongst the local sportsmen. Harry Vardon not only played in the tournament, but won it – his first professional tournament win.

Young Rickwood may have caught his first glimpse of Harry Vardon at this event.

Englishman George Rickwood could not have anticipated that his son Fred would grow up to be a professional golfer. When Fred Rickwood was born on December 28th, 1882, in Ilkley, Yorkshire, there were only about 12 golf courses in all of England, and none of them was in Yorkshire. In the town of Ilkley, where George and Annie Rickwood were raising their family, there would not be a golf course built until 1890, when Ilkley Golf Club (the third oldest in Yorkshire) was established. Young Fred, their eighth child, was just seven years old then.

Figure 3 19 Tivoli Place, Ilkley, Yorkshire (left side of the house).

Fred’s father George was a gardener, proud of the work he did. He was careful to indicate to the census taker that he was “not a domestic gardener”: that is, he wanted the record to show that he was not a domestic servant, but rather a self-employed gardener.

And he made a good living. On the money he earned, he and his wife Annie successfully raised a family of ten children to adulthood. As the size of the family increased, the Rickwoods moved from Nelson Street in downtown Ilkley to Tivoli Place. It was a move of just 100 yards – Tivoli Place was just as much downtown as Nelson Street – but more importantly it was a move from a house with two storeys to a house with four storeys.

The new house was only a small step up in the real estate market, but the key was that it had more rooms: that is, more bedrooms for children. Although the twelve members of the family never lived in the same house all at the same time (since the oldest ones had moved out by the time the youngest were born), it was clear by the time Fred was born that the family needed more room.

For decades after this move from Nelson Street to Tivoli Place, the Rickwood family lived comfortably in its new home. The house was in a good location, just 200 yards from the railway station, and just 500 yards from the town centre. Shops, schools, and hospitals were within walking distance, and in late- Victorian Britain, which rolled along on railway tracks, most of England, Scotland, and Wales could be reached from the Ilkley railway station. The location of their home at Tivoli Place was so central and convenient that as their children grew up and left to make their way in the world, George and Annie Rickwood never lacked for lodgers to rent a vacant bedroom. From the 1890s through the early 1900s, in fact, there were always one or two lodgers in the house at Tivoli Place.

Like George Rickwood, the men listed as the heads of the neighbouring households were skilled workers. In particular, several of the neighbours were joiners and carpenters. The joiner was the more sophisticated wood worker who joined wood into doors, stairs, door- and window-frames, and much more ornamental constructions, including cabinets, bookshelves, tables, chairs, and other furniture. Joiners tended not to work on a construction site, but rather to work in a shop, since in those days the machinery required to do their work tended to be heavy and not very portable.

Fred’s oldest brother William was apprenticed as a joiner, and was still listed in the census as an apprentice in 1891 when he was 19. He was probably serving his apprenticeship with one of the neighbours who were joiners – perhaps right next door to the Rickwood home where the neighbour was a joiner– a joiner who had taken on his own son as an apprentice.

The presence of joiners not just next door to Fred Rickwood, but also within his own household, no doubt played a role in Fred’s apprenticeship to a golf professional. Since golf club making was an essential art of the golf professional at the end of the nineteenth century and beginning of the twentieth century, and since golf club technology in those days inevitably required the joining of wood shafts to wood or steelclub heads, there was a natural migration of joiner skills into the golf club making profession. Indeed, Donald Ross himself (the most important golf course architect in early American golf history) served five years as an apprentice joiner in Dornoch, Scotland, before signing on with Old Tom Morris as an apprentice golf club maker (returning with Old Tom to St. Andrews after Ross observed him working on the links course at Dornoch in the mid-1880s).

Even such knowledge of gardening as Fred Rickwood picked up from his father would have stood him in good stead when approaching a professional golfer about the possibility of serving an apprenticeship with him, for the professional golfer was also his golf club’s greenkeeper. Harry Vardon’s own father was a professional gardener, for instance, just like George Rickwood, and it was his good reputation as a gardener on the island of Jersey in the English Channel that led the golf professional on Jersey to employ Vardon’s father as the greenkeeper there. The Vardon boys Harry and Tom, both of whom would become successful professional golfers, not only served as caddies at the Jersey golf course, but also helped their father to maintain its greens.

It is even possible that Fred Rickwood’s father was the greenkeeper at Ilkley Golf Club and that it was through his father that Fred came to work there.

But whether or not there is any truth to such speculation, the fact is that every golf apprentice started as a golf caddy, and every caddy invariably attempted to play the game that he had learned as a caddy (usually having to fashion his own primitive golf club out of branches gathered from a nearby woods – as both of the Vardon boys had done on Jersey). The golf professional would organize a tournament for his golf course’s caddies and would select the caddy or caddies with an aptitude for the game as his apprentices.

Figure 4 Tom Vardon circa late 1890s.

At Ilkley Golf Club throughout the 1890s, Tom Vardon was the golf professional, and he maintained there a stable of five caddies. The Wharfedale & Airedale Observer notes that the Ilkley Golf Club’s 1894 statement of accounts shows that “£164 was paid last year to the caddies. There are but five of them. This represents an annual income of £35 each, not a bad income for a boy” (28 Sept 1894, p. 8). A working-class boy like Fred Rickwood would have thought of £35 as a fortune!

Note that in those days, professional golfers were second-class citizens at their own golf clubs.

They were paid little, making most of their income from golf instruction and the sale of golf balls and hand-made clubs (there were few golf tournaments, and prize money was available only for the top five or six finishers). Golf professionals were members of the working class and were treated by the gentlemen and lady members of the golf club as tradesmen. The professional golfer was not allowed in the clubhouse, keeping instead to the golf professional’s shop where the golf clubs were made and golf equipment was available for sale to club members. No golf professional was ever invited to become a member of the golf club where he was employed before Harry Vardon himself became the first golf professional accorded this honour by his own golf club in 1930.

So of course caddies were also from the working class and were treated with even less respect than professional golfers. Yet they were essential to the game, as no gentleman carried his own clubs. Rather, boys not yet ten years old were recruited to carry clubs for members. Well into the twentieth century, any boy who continued to caddie beyond his sixteenth birthday officially became classified as a professional golfer.

The original Ilkley golf course was located on Ilkley’s Rombalds Moor just one mile from Ilkley Station, and an even shorter distance from the front door of the Rickwood’s home, so young Fred Rickwood could easily have caddied there without needing anything but his own two feet to get him to work and back.

Figure 5 George Strath (1849-1919), who caddied for Old Tom Morris at St Andrews and learned from him how to lay out golf courses.

Several months after the first Ilkley golf course was laid out on Rombalds Moor by Scottish professional George Strath in June of 1890, a reporter from the nearby city of Leeds came out to the little town of Ilkley to discover just what the strange Scottish game being introduced into Yorkshire was all about. He arrived at the Ilkley train station and walked right past the Rickwood home in search of the golf course and the golf professional. Arriving at the clubhouse, he encountered a caddie:

Golf, like many other Scottish institutions, seems to have taken firm hold in this country, and the Ilkley Club is only one of many similar bodies which have been formed in the last year or two in England…. Yesterday I visited Ilkley for the purpose of gaining what information I could about the club and the game.

On reaching Ilkley I was informed that the links lay just above Wells House, and on getting there, I observed a boy knocking a ball about with a golf club on the tennis lawn of the establishment. He told me that those were the headquarters of the Golf Club, and that the professionalwas on the links just up the road. Thither I accordingly went, and though I saw no professional, there were unmistakable signs of the links, in the shape of a flagstick stuck into a hole in the centre of a smooth piece of grass, which was strangely in contrast with the surrounding moorland. (Leeds Mercury, 6 December 1890).

Figure 6 Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, 30 January 1892, p. 14.

An artist illustrated the clubhouse a year later, depicting a golfer apparently engaging a caddie for a round of golf. The caddie in the illustration and the caddie in the reporter’s story could well have been a young Fred Rickwood. And if a working-class teenaged schoolboy named Fred Rickwood had indeed been earning money caddying at the Ilkley golf course and had impressed the club’s professional golfer Tom Vardon with his aptitude for the game, such a golf-savvy son of a gardener and brother of a joiner could very well have talked his way into an apprenticeship.

Figure 7 Tom Vardon studio photograph circa 1903.

Of course Tom Vardon was Harry Vardon’s younger brother, and his fame was less than his brother’s. But he nonetheless had quite a high standing in the golfing public’s awareness. The Golf Annual of 1897 referred to Tom and Harry Vardon as “the two brothers who have, during the last five years, taken their places at the forefront of the professional ranks” (vol 10 p. 59).

The preeminent golf writer at the beginning of the twentieth century, Bernard Darwin, wrote of Tom Vardon as follows: he was “a very fine, dashing golfer, of a cheerful character, who took the game more lightheartedly than his brother. He was not a pretty player, with his right thumb down the shaft and a perceptible lift – it might be called a jump – in his up-swing. But he was uncommonly good.” Harry would become the most accomplished golfer of his generation, but Tom had his own considerable accomplishments. He held half a dozen course records by 1897 and would shortly thereafter finish second in one of the British Open Championships his brother won. In total, Tom Vardon would play in fifteen British Open championships. He later immigrated to the United States, where he regularly played in the US Open, becoming the oldest player to qualify for the 1930 US Open in Minnesota.

Figure 8 Harry Vardon and Tom Vardon (seated) on the England golf team versus Scotland in 1903.

At Ilkley Golf Club, Tom Vardon was charged not only with maintaining a golf course and serving the club members as their professional golfer, but also with introducing golf to Ilkley and the surrounding communities. He convinced Harry to come to Ilkley in 1893 to help raise the profile of golf in the town by entering the professional tournament that the Ilkley Golf Club was hosting. As mentioned above, Harry Vardon won that tournament, his first professional victory.

And the Ilkley Golf Club thrived.

One of its early members after it moved in 1898 to the river valley was Dr. Alister Mackenzie who collaborated with Bobby Jones in the construction of Augusta National Golf Club in the early 1930s. He remembered Ilkley Golf Club fondly in his 1933 article “Water Holes Should Tempt, Not Torture” (Golfing, January 1934): “There was a club I belonged to more than thirty years ago, Ilkley, in England, where Tom Vardon was the professional. A river ran through the grounds.” So the young Mackenzie no doubt followed Tom Vardon’s construction of the new course with great interest, and may have discussed the work with him.

In 1912, having become a famous golf course architect in his own right, he returned to Ilkley and rebuilt their 15th hole for free, as what he called “a labour of love.” Today, Ilkley Golf Club’s most famous professional alumnus is Colin Montgomerie, who still holds the course record.

Tom Vardon loved to tell stories afterwards of how Yorkshiremen of the 1890s (such as the young working-class boy Fred Rickwood, perhaps) reacted to the new game that the Ilkley Golf Club brought to town: “When I went to Ilkley golf was only just beginning there, and everything connected with it was in a very raw state. But we soon got going well, and by and by we had a most successful club …. The Yorkshire natives were in a delightful and sometimes inconvenient state of ignorance about the game. The main road from Keighley to Ilkley cut through our links … and the Yorkshiremen who were on the road at the time a ball found its way there were a dreadful trouble. They always … and invariably, out of

the goodness of their nature, picked up the ball and handed it to the player” (252-53).

The road was regarded as a “natural” hazard in the 1890s: as it preceded the golf course, it became part of the holes that crossed it, and so shots had to be played from the road, which is visible curving across the bottom left side of the sketch below showing golfers and caddies on the Ilkley course circa 1891.

Figure 9 Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, 30 January 1892, p. 14.

Vardon also noted the enthusiasm of Yorkshire workmen for the gentlemen’s game: “There was some talk of starting a workmen’s golf club there, and two Yorkshire novices who knew nothing about the game, but were burning with enthusiasm for it, made a match to play each other for what was for them a considerable stake…. Neither had ever played before, but one was a much stronger man physically than the other, and it was agreed that he should on this account concede his opponent a start of four holes in the round of nine …. I was told that quite a crowd followed the game, and later on I was requested to settle a dispute that occurred at the outset. There was a wall going to the first hole, and the man who was conceding a start of four holes got his ball under this wall and was quite unable to get it out again. Consequently he lost the hole, and thereupon his opponent, now five up, claimed the match, his argument being that as the match was one of nine holes, and he was already five up, he was obviously the victor. It was no use explaining to him that the four holes with which he was presented at the start did not count as four of the nine to be played” (Great Golfers in the Making, ed. Henry Leach, London: Methuen, 1907, 2nd ed., p. 253).

If Fred Rickwood began to learn the art of club-making from Tom Vardon, he was learning from a master. The hand-made golf clubs from Tom Vardon’s professional golf shop were highly sought-after, not just by club members, but also by members of the public more generally. The following is an example of the kind of advertisements placed in Yorkshire newspapers: “Golf Clubs! Golf Clubs!! The celebrated clubs made by Tom Vardon, the Ilkley Pro, can be obtained at … W Benson’s, the Sports’ Goods & Saddlery Stores” (20 September 1895, p. 1).

Tom Vardon also mentions that a new course had to be built during his tenure as golf professional at Ilkley and that it almost immediately had to be renovated after the new course was devastated by the great Ilkley flood of July 12th, 1900: “When I was at Ilkley we changed our links, and I shall never forget what happened soon after we had got onto our new course, which was low down and quite close to the river, instead of being on the moors, where the original one was. A great cloud burst quite close to us, and for two hours water poured onto the course as I have never seen it pour before or since. Afterwards there was mud on the course quite eight inches deep, and it cost us £150 to get rid of it. At the same time in Ilkley, the water-mains in Ilkley were burst, houses were torn down, and one man was killed.” (Great Golfers in the Making, p. 253).

The Wharfedale & Airedale Observer reports that the Ilkley Golf Club had leased an “extensive piece of land adjoining the river” as of March, 1898, so the new course would have been under construction along the River Wharfe from 1898 to 1899. If Fred Rickwood was apprenticed to Tom Vardon at this time, there is no doubt that his first experience of golf course construction would have come during this building of the second golf course at Ilkley.

And it would seem that according to Rickwood family lore, Fred Rickwood indeed had a role in the construction of the Ilkley golf course. When his son Robert and daughter-in-law Ruth visited Ilkely as tourists in 1968, Ruth wrote a letter to the Ilkley Gazette explaining that her father-in-law “was a prominent golfer in the Ilkley area and laid out the Ilkley Moor golf course” (cited by Jim Seton, “Across the Years,” Ilkley Gazette, 18 January 2018). As young Fred would have been just eight years old when the Moor course was built, however, family lore would seem to have confused the Moor course of 1890 with the River Wharfe course built in the late 1890s, but there can be little doubt that Rickwood told his children that he had been involved in the building of the Ilkley golf course.

Figure 10 The original seventh tee at Ilkley Golf Club, circa 1910.

So if Fred Rickwood entered the game as a caddie at Ilkley Golf Club, as seems likely, and then graduated to an apprenticeship there under Tom Vardon, he would have learned all aspects of the game at this time – from playing it, to making and selling the equipment for it, to building and maintaining the course upon which it was played.

He may even have had occasion to make a golf club or two for early club member Alister Mackenzie, or perhaps even to discuss golf course design with the future great architect!

There is a photograph taken between 1898 and 1900 of Tom Vardon and the greenkeeping staff that he had assembled to tend to the newly built Ilkley golf course located along the River Wharfe. In the photograph below, Vardon stands to the right of a group of four members of the greenkeeping staff. According to the Leeds Mercury, by the summer of 1899, “The ground staff now comprised two permanent men, two boys and a horse” (31 July 1899). We can see the horse in question, but we see four men beside Vardon, rather than two men and two boys.

Figure 11 Tom Vardon stands to the right of his Ilkley Golf Club greenkeeping crew.

But there is another person in the photograph, a boy standing at the top of the clubhouse steps.

Figure 12 A boy, perhaps Fred Rickwood, stands on the Ilkley clubhouse steps while Tom Vardon is photographed with the ground staff.

This young person may well have been Vardon’s apprentice, perhaps seventeen-year-old, fair-haired, five-foot, seven-inch Fred Rickwood.

With Vardon out on the golf course having his photograph taken, his apprentice would have stayed at the pro shop. Note that the new clubhouse had a separate room built for the golf professional’s shop, whereas the Rombalds Moor clubhouse did not.

Tom Vardon was popular as Ilkley Golf Club’s golf professional, but in 1900 he decided to leave the club for a more lucrative contract at Royal St. George’s Golf Club in the south of England:

Very much to the regret of the Ilkley Golf Club members, it has become an open secret that Tom Vardon, who has been “guide, philosopher, and friend” to Ilkley golfists for some nine years, is about to sever his connection and take up a more lucrative position as professional to St. George’s, Sandwich, Kent, and a course second to none in England. To Ilkley golfers, by whom Tom has been held in the highest esteem, this intelligence has occasioned very wide regret, and in other circles, wherein he has made friends, his removal, which will take place about October 10th, will create a void difficult to fill. (Leeds Mercury, 22 September 1900, p. 21)

His departure for Sandwich was a little bit later than anticipated, but the delay allowed the Ilkley golf Club to plan an event to express its appreciation of his service to the club:

Presentation to Tom Vardon

On Saturday afternoon a large number of members of the Ilkley Golf Club assembled in the club house to attend a presentation to Tom Vardon, the professional of the club, who is about to remove to Sandwich. Over £50 had been raised for the testimonial, which took the form of a silver tea and coffee service and tray, and a cheque for £26. On the tray was inscribed, “Tom Vardon, with best wishes from the members of the Ilkley Golf Club.” He also received a diamond pin and stud and a silver pencil case from the lady members. The President of the club (Mr. B. Hirst), in making the presentation, spoke of the many qualifications of Tom Vardon as a golf professional. As a teacher his success had been evident from the time he joined the club, now nine years ago. His honest, cheery nature, his anticipation of the wants of others, and his unfailing courtesy under all circumstances made him popular with the members, visitors, and all with whom he was brought in contact. There was of course no option for him but to accept the offer made to him to become professional to the St. George’s Club, which ranked as possibly the most prominent of all English clubs. They all regretted the termination of Vardon’s association with Ilkley, and asked him to accept those tokens of their esteem, and the best wishes for his future welfare. (Applause.) Mr. A.W. Godby, one of the secretaries, also expressed the high appreciation in which Vardon was held, and said that there had never been a disagreement between Vardon and the committee that had left an unpleasant feeling behind. The Sandwich Club was to be congratulated on obtaining the services of so good a professional…. Tom Vardon suitably acknowledged the gifts, and expressed his own appreciation of the many kindnesses he had received while at Ilkley. He greatly regretted leaving Ilkley, but, as the president had said, he had no option under the circumstances. He commended his successor to the members, and said he hoped to have some opportunity in future of playing a game on the Ilkley links. (Applause.) (Leeds Mercury, 29 October 1900, p. 10)

The value of the gifts he received was significant – worth more than ten times the cash prize that his brother had been awarded when he won his first tournament at Ilkley in 1893.

When Tom Vardon left Ilkley, Fred Rickwood would have been able to move from his apprenticeship under the one Vardon brother at Ilkley to a continuing apprenticeship under the other Vardon brother at Ganton, all without having to leave Yorkshire. His family background would have been particularly interesting to Harry Vardon, for not only was Vardon’s father a professional gardener like Rickwood’s father, but Vardon himself had actually turned to gardening as a profession for five years, playing golf only on holidays at that time, before he became a golf apprentice late in his teens.

On the other hand, even before Tom Vardon left Yorkshire, Harry Vardon might have poached apprentice Rickwood from his younger brother Tom, for he was known to have poached other promising apprentices from other professional golfers.

Harry Vardon's Apprentices

Harry Vardon had three apprentices serving under him at Ganton by 1900.

Figure 13 Percy Barrett circa 1905 with his notorious 22- inch putter. He finished 3rd that year in the US Open.

One of them was Percy Barrett. Barrett was learning the life of a professional golfer from Vardon at work, rest and play, for he not only worked in Vardon’s professional golf shop at the Ganton golf course, but also boarded with Vardon and his wife Jesse.

Barrett immigrated to Canada in 1903 and became the professional golfer that year at Lambton Golf and Country Club where he also built the original nine- hole golf course. He finished third in the 1905 US Open, he won the 1907 Canadian Open, and he won many professional golf tournaments in Ontario in later years. The talk throughout Barrett’s career was that he had the potential in terms of his exceptional abilities for much greater golf success than he achieved but lacked the temperament required to close out tournaments with victories.

One of the Canadian professionals who had also competed in the 1905 U.S. Open, Charles Murray, of Montreal, returned from the tournament and explained that Barrett not only “did well,” but that he had pretty much thrown the title away with putting yips: “In fact, Barrett lost his chance on two greens where three extra strokes cost him first place” (Montreal Gazette, 28 September 1905, p. 2).

When Barrett died prematurely in 1927, he was remembered in the Montreal Gazette as Harry Vardon’s first apprentice (“pupil”): news of “the late noted golfer” was “conveyed in a cable to Harry Vardon, who recommended Mr. Barrett to the Lambton Golf and Country Club in 1903 as his first pupil” (Montreal Gazette 25 January 1927). Vardon subsequently told Canadian Golfer that of the dozens of apprentices that he had had over many years, there had never been one better than Barrett.

Figure 14 1911 Canadian Open Players at Ottawa Golf Club who founded the CPGA afterwards. Rickwood is seated in the centre of the photograph, three men to his left and three men to his right..

Rickwood and Barrett seem to have been good friends. Many years later, in 1923, Rickwood played an exhibition match in Barrie, Ontario, with Barrett as his partner against two other professionals.

This exhibition match was officially undertaken as an act of charity in support of the Victorian Order of Nurses, but the newspaper accounts make it clear that the match was also intended to promote the game of golf in Barrie: “Such an exhibition of golf as played by four ‘pros’ should help to boom the game in Barrie. It was with this object that these professionals came without charge to Barrie and also for the purpose of helping such a worthy cause as the Victorian Order of Nurses” (Barrie Examiner 23 August 1923 p. 1). And when we learn that the golf professional at Barrie was Jack Roberts, a young man who, just the year before, was the assistant professional at the Summit Golf and Country Club to Fred Rickwood who was then the head pro at Summit, we can see that it was Rickwood who, in support of his own former apprentice, called upon Percy Barrett to partner with him in an eighteen-hole match against the other two golfers: the one, his friend (and soon-to-be business partner) William Brazier, and the other, Andrew Kay, that year’s winner of the Ontario Open championship.

In connection with this evidence of a longstanding bond of friendship between Rickwood and Barrett, we should also note that Rickwood married a woman whose name was Edith Florence Barrett. She may well have been a cousin of Percy Barrett’s whom Rickwood met through his association with Percy Barrett. I also note that Percy Barrett married a woman named May Owen – Owen being also the maiden name of Rickwood’s mother, Annie. The families may have had connections back in Yorkshire. No evidence of relatedness amongst these families has emerged in my research so far, but I mention these possibilities nonetheless.

Incidentally, Percy Barrett was known to the Napanee Golf Club even before its future designer Fred Rickwood was, for it was Barrett’s golf apprentice Harry Robinson that Napanee Golf Club hired in 1923 to serve as its professional golfer. Robinson, born in 1900, boarded with Barrett and his family in 1921 – just as Barrett had boarded with Harry Vardon twenty years before. The Napanee Beaver reported that the “Napanee Golf Club has secured the services of Mr. H. Robinson as Professional for the coming season. Mr. Robinson, who is a pupil of the well-known Professional, Percy Barrett, late of Lambton and Weston Clubs, won the tournament for Professionals’ Assistants in 1922 and comes well recommended. He will be ready to give lessons to members of the Club commencing Monday next, May 7th. Mr.

Robinson will alternate between the Napanee and Picton Clubs during the coming season, spending half a month at each Club” (4 May 1923).

It was actually the Assistants tournament of 1921 (not 1922) that Robinson won (and he won by eight strokes, with the Canadian Golfer observing that “H Robinson of Weston rather romped away with the rest of the field” [August 1921, vol vii no 4, p. 244]), but it is nonetheless clear here that in the 1920s the professional genealogy of golf apprentices was seen as important. Barrett’s having served an apprenticeship under Harry Vardon was always noted in the newspapers and magazines, and even in out-of-the-golfing-mainstream Napanee Robinson’s apprenticeship under Barrett was noted.

I wonder if Napanee Golf Club knew that not just Percy Barret but also Harry Vardon was in Robinson’s “family tree” of professional progenitors – as his grandfather, so to say.

Also an apprentice for Harry Vardon when Barrett and Rickwood were apparently serving together in the Vardon club-making shop at Ganton around 1900 was George Sargent.

Figure 15 George Sargent circa 1909.

Sargent had been the professional Golfer at Ottawa Golf Club a few years before the Canadian Open was hosted there in 1911, but had moved on to a golf club in New Jersey by 1911, where Sargent designed the golf course himself. Sargent won the 1909 US Open nine years after his mentor Vardon did and afterwards was commissioned to write an article about his development as a golfer. In it, he refers to the experience of having been Vardon’s apprentice at Ganton between 1899 and 1900: “Like nearly all prominent professionals, I commenced my career as a caddie lad…. I continued as a caddie until nearly twelve years old, when I commenced my

apprenticeship to Tom McWatt, who was … professional to the Epsom Golf Club. As a club maker, I had nearly six years under McWatt and got fairly well drilled in the art of club making and was also playing a fairly good game; in fact, at 16 years of age, I could hold my own with a scratch man…. It was while I was with McWatt I first saw Harry Vardon.

He and Jimmy Braid were playing an exhibition match over Epsom; Harry Vardon had won his first championship that year [1896]. They were looking round the club maker’s shop as professionals usually do, and McWatt showed them a head I had made, and told them I had been only three years at the trade. They were both very much interested and asked me a number of questions as to my playing, Vardon saying, ‘Well, laddie, you may be a champion yourself some day’ …. After nearly six years with McWatt, I went under Harry Vardon at Ganton, which was about the time he was at his best [Vardon won the British Open again in 1899 and 1900]. He would challenge three of us out of the shop, then we were like the cow’s tail – all behind” (“How I Won the Open Championship,” American Golfer, vol 2, no 2 [July Supplement 1909], pp. 89-90).

Figure 16 George Sargent's US Open win in 1909 celebrated in cartoon, American Golfer (2 August 1909), p. 163

Rickwood was probably the third of the three apprentices running out the shop door all in a “cow’s tail” to join the head professional Harry Vardon in those impromptu golf matches in 1900. And quite a foursome it was: golf’s first superstar Harry Vardon, 18-year-old US Open champion-to-be George Sargent, 18-year-old Canadian Open champion-to-be Percy Barrett, and 18-year-old Napanee golf course designer-to-be Fred Rickwood!

When Harry Vardon returned to his apprentices from his first exhibition tour of North America in 1900, he recommended to them that they go to North America: the game was about to “boom” there.

Barrett, Sargent, and Rickwood all followed his advice, and the game did indeed boom in Canada – thanks in part to contributions from all of them.

Little Fred's Little "Z"

The 1901 Census of England and Wales (taken on the night of March 31st) indicates that 18-year-old Fred Rickwood was living back home in Ilkley that day. In addition to providing the usual information about his age, his sex, his reading and writing ability, and so on, it records that he was employed and that he was a worker rather than an employer.

Interestingly, his occupation was recorded as “z.”

The letter “z” was used by census takers in England and Wales to indicate a job that they did not know how to categorize. The government provided its census takers with a list of jobs and professions that were to be recorded in terms of a list of codes made up of letters and numbers that the census taker was supposed to enter on the census form. Recall that when George Rickwood learned that his profession would be recorded by the code for “gardener,” he insisted that it be noted he was “not a domestic gardener.”

“Z” was the letter to be recorded for all jobs that flummoxed the census taker.

Census takers and immigration officers in the early 1900s in Britain, Canada, and the United States did not know quite what to make of professional golfers. Presumably very few census takes were familiar with the game.

Having won three British Open championships by 1900, the great Harry Vardon nonetheless was judged by the 1901 census taker in Ganton to be a golf club maker. His much less great brother Tom, however, beaten by his brother Harry in each of these competitions, was nonetheless, according to the Ilkley census taker, a “professional golfer.”

Other professional golfers and apprentices were recorded as “golf instructors,” or simply as “instructors.” Rickwood himself, for instance, had graduated from “z” by the time of the 1911 Canadian census and found himself recorded as an “instructor” and as a “keeper of a park.” When William T. Brazier immigrated to Canada in 1912 as a 20-year-old, the Maritime immigration officer recorded that he was a “golf caddy,” although he was well beyond his caddy years.

Having won the US Open in 1909, George Sargent instructed the 1910 US census taker to put down that his occupation was “Golf Champion”!

Ironically, Sargent’s replacement at the Ottawa Golf Club, Karl Keffer, a “Golf Champion” himself, having won the Canadian Open in 1911 (the same year Sargent won the US Open), was living in an apartment within the clubhouse as the Ottawa Golf Club’s professional golfer when the 1911 Canadian census was taken: his employment was recorded as “Servant.”

First Soldiering

In the middle of 1901, several months after the England and Wales census was taken, 18-year-old Fred Rickwood decided to join the British Army in order to fight in the second of Britain’s wars against the Boers in South Africa.

The war, originally called the Boer War, but now called the Second Anglo-Boer War, lasted from 1899 to 1902.

It began as something of a grand crusade to subdue the rebellious Boer population in South Africa to the will of the British Empire. The war was supposed to have been quickly won. Yet from the beginning, the most powerful country on earth, which controlled much of the world via its globe-circling empire (on which, it was said, the sun never set), was regularly thwarted and stymied by the guerrilla warfare tactics of the vastly outnumbered and outgunned Boers.

To prevent the guerilla fighters from being supplied, the British destroyed crops, on the one hand, and depopulated rebellious regions of both their white and their black inhabitants, housing them instead in a system of concentration camps, which were poorly administered and tended to cause disease, and thereby thousands of deaths.

By 1901, not surprisingly, given the failures of the army and the brutality of its tactics, the first flush of enthusiastic enlistment in Britain was well in the past. In fact, the war had become a national embarrassment.

Undeterred by negative coverage of the war in the newspapers, however, and undaunted by a death toll already higher than the death toll Britain had suffered in the Crimean War fifty years before, patriotic young Fred Rickwood enlisted in a Yorkshire battalion (the 35th) of the volunteers known as the Imperial Yeomanry, a cavalry unit.

When the first contingent of Imperial Yeoman Volunteers was formed in 1899, the middle-class gentlemen volunteers for this unit brought their own horses with them, as was officially required. Yet by the time the third contingent, which Rickwood joined, was raised in the middle of 1901, the by now primarily working-class volunteers who made up the vast majority of recruits could not have been expected to do so. Still, whether or not Fred Rickwood had his own horse or had any experience with horses before the war, he came to know all about them by war’s end.

Unlike the poorly trained contingent of Imperial Yeomanry sent to South Africa early in 1901 (units that participated in – and were in some respects blamed for – significant defeats, entailing large numbers of casualties), Fred Rickwood’s contingent was much better trained. Rickwood and his fellow volunteers were housed in barracks in Yorkshire for several months and given a level of military training similar to that bestowed upon the members of the regular professional army. He and his fellow recruits of 1901 were to be proper soldiers.

Figure 17 Cavalry troopers of the properly trained third contingent of volunteers known as the Imperial Yeomanry.

After rigorous training, Rickwood’s battalion was sent to South Africa, horses and all, in the late spring of 1902.

Mere days before Rickwood’s battalion reached Pretoria after many weeks at sea, however, a peace treaty between Britain and the Boers was signed in June of 1902. Members of the various units of the Imperial Yeomanry sent to South Africa in June of 1902 who got off the troop transport ship in Pretoria as late as the hour that the treaty was signed received a South Africa Service medal. But those who were travelling to South Africa when the treaty was signed – even those whose ships had anchored in Pretoria harbour but who had not yet disembarked – did not receive a South Africa Service medal.

Success in life, as in a golf swing, depends on timing: Fred Rickwood did not get off the boat in time to get a medal. Yet neither did he become a casualty of that brutal war, as did so many in the battalions of the Imperial Yeomanry deployed earlier in the war. Success is relative.

Although the Boer war was over before Rickwood arrived, his volunteer battalion remained in South Africa for the better part of a year.

The units of the Imperial Yeomanry like his that remained in South Africa after the treaty was signed were charged with the responsibility of ensuring that the terms of the peace treaty were properly observed. In effect, they served as a police force.

We can see from the photograph to the left that the fully armed and outfitted Imperial Yeoman, mounted on his horse, could certainly cut a rather imposing figure.

Finally, however, in the spring of 1903, Trooper Rickwood was sent home.

First Canadian Golf: Toronto

What Fred Rickwood did after his return to England from South Africa is not clear.

According to the information they provided the census taker in 1911, Fred Rickwood and his wife Edith Rickwood both immigrated to Canada in 1908. On a simple reading of the census information, one could be forgiven for thinking that they arrived in Canada in 1908 as a married couple, but in fact they immigrated to Canada separately as single people, and they did so in different years.

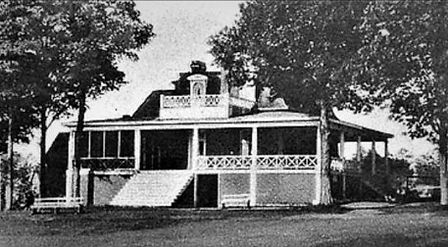

Figure 19 The clubhouse of the Toronto Golf Club, early 1900s, where Edith Barrett lived and worked when she arrived in Canada.

As a single woman, Edith Florence Barrett arrived in Halifax in March of 1908, describing herself as a “Domestic” on her way to Toronto.

In Toronto, she ended up living at the Toronto Golf Club, presumably employed as part of the support staff.

The Toronto Golf Club had been established in 1876, preceded as a golf club in Canada only by the (Royal) Montreal Golf Club (1873) and the (Royal) Quebec Golf Club (1875).

Note, however, that the Toronto Golf Club’s golf course has changed locations several times over the years.

When Edith Barrett lived at the Toronto Golf Club, its golf course was located in East Toronto, precisely where we find a young man named Fred Rickwood living at this time.

When Fred Rickwood arrived in Halifax in March of 1911, returning from his stay at his parents’ home in Yorkshire during the 1910-11 winter, he gave the immigration officer information about his original arrival in Canada different from the information provided to the census-taker two months later. He indicated that he had first come to Canada eight years before (which would have been in 1903), and that he had lived in Toronto at that time.

His death certificate provides different information yet again. It indicates that, according to his wife of thirty years, he had been in Canada only since about 1905.

It is possible that Rickwood first came to Canada in 1903, perhaps with Percy Barrett, who established himself in Toronto as the builder of the first Lambton golf course and as the Lambton Golf Club’s first professional golfer. Perhaps Rickwood helped him to build the golf course. Barrett returned to Yorkshire during the 1903-04 winter, and played golf at Ganton (although Vardon had been replaced there by Ted Ray more than a year before), so even if Rickwood had not travelled to Canada and back with Barrett, it is possible that Rickwood met him when Barrett came back to Yorkshire.

But I have found no records yet of Fred Rickwood’s having arrived in Canada in 1903.

Yet there is indeed a Canadian immigration record that shows that a twenty-two-year-old Fred Rickwood, who states that he was born in Yorkshire, arrived in Nova Scotia on 7 April 1905. The age indicated for this immigrant is Fred Rickwood’s age in 1905, and a 1905 arrival date is consistent with the information on Fred Rickwood’s death certificate.

This would seem to be our man.

Ottawa golf historian Margaret McLaren informs me that Rickwood sailed on the Bavarian, one of the fastest ships of the Allan Line (email to author, 16 June 2022). Departing from Liverpool on March 30th with 1504 passengers, the Bavarian encountered very little ice on its crossing and nearly beat its own record for one of the fastest crossings of the Atlantic:

The Bavarian, which arrived [in Halifax] last evening, had a fine trip, and came very near repeating her record of six days and twenty-three hours. She covered the total of 2,515 miles … in seven days…. [T]his morning her second- and third-class passengers were landed. The passengers are a fine lot – young, clean-looking, and bright – the majority of them coming from the British Isles. (Evening Mail [Halifax], 8 April 1905, p. 16)

Figure 20 S.S. Bavarian, circa 1905.

Rickwood may have travelled on the S.S. Bavarian even before immigrating to Canada, for the ship was used during the Boer War, from 1899 to 1902 transporting artillery, troops, sick and wounded soldiers, and so on. The ship was wrecked in the fall of 1905 when it hit Wye Rock at Grosse Ile in the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

Upon his arrival in Halifax, Rickwood told Canadian immigration authorities that his job was that of “Platelayer.”

A platelayer was an employee of a railway company who inspected and maintained railway track (rails, sleepers, fishplates, bolts, etc.). The platelayer inspected rails and components for wear and tear and maintained parts by greasing them. When sections of track required complete replacement, larger teams of platelayers worked together on such jobs.

Upon his return from South Africa, rather than briefly visiting Canada in 1903, it seems likely that Rickwood was employed for a year or two by one of Britain’s many railway companies. Before that, he may even have returned to his apprenticeship with Harry Vardon.

In any event, when Rickwood arrived in Nova Scotia in 1905, he said he was on his way to Toronto. Presumably his train journey to Toronto across eastern Ontario would have given him his first view of the Napanee golf course. The golf course was virtually treeless in the area where the five-hole course then operated, and all five holes were right beside the train tracks, so if anyone was playing golf on the day his train rolled by, Rickwood could have easily seen them. He would not have seen any flags flying in the golf holes, however, for, as we shall see (in the second volume of this book), the holes were then marked only by short poles, about three feet in height, with a bit of rope or cloth bound to the tip.

Whether or not he could see the golf course in 1905, what he certainly could not have seen was what lay in his future: an enduring connection to Napanee’s track-side golf course.

Rickwood had told immigration officials that he was on his way to Toronto. In fact, he travelled beyond Toronto to Waterloo, Ontario. Just weeks after his arrival in Canada, we find that he has found work in a rural community called West Montrose, about ten miles north of Kitchener-Waterloo. According to the Chronicle-Telegraph (Waterloo, Ontario), “Mr Fred Rickwood, formerly a soldier in the British army in South Africa, has engaged with Byron Letson for the current year” (18 May 1905, p. 1). Letson (1871-1950) was a farmer who lived on the farm he owned in West Montrose his whole life.

Rickwood, however, was not to stay long in West Montrose. The newspaper indicates that Rickwood still had Toronto on his mind: “Mr Fred Rickwood, of West Montrose, spent some days in the Queen City last week and reports a good time” (14 September 1905, p. 1). He must have moved to Toronto by at least 1906, for we find a report in the Waterloo Chronicle-Telegraph that he had returned to the area for Christmas at the end of 1906: “Mr. Fred Ric[k]wood of Yorkshire, paid a Christmas visit to West Montrose” (3 January 1907, p. 1). He had lived in west Montrose for perhaps a year, yet he seems to have made significant friendships.

In regard to Rickwood’s visit to Toronto late in the summer of 1905, I note an interesting conjunction of golf figures in Mississauga at precisely this point.

In 1905, the shareholders of the newly formed Mississauga Golf Club bought 208 acres of land on the former Mississauga Indian Reserve that had been in private hands for fifty years. The next year, “George Cumming and Percy Barrett, professionals at the Toronto and Lambton golf clubs, surveyed and laid out a nine-hole course” (Paul Dilse, Heritage Impact Statement on the Pump House at the Mississauga Golf and Country Club, for the Mississauga Golf and Country Club and the City of Mississauga [11 Octo012], p. 5). So here we have Rickwood’s fellow Vardon apprentice from the early days in Yorkshire working with the most important professional golfer in Canada. Shortly afterwards, Rickwood moved from West Montrose to Cumming’s neighbourhood, right next to the Toronto Golf Club.

It is possible that Rickwood gave up farm labbour for work on this new golf course project in Mississauga.

Cumming and Barrett worked closely together in 1905-06 not just as architects, but also as players. In December of 1905, we read in The Daily Morning Journal and Courier (New Haven, Connecticut) that George Cumming, of the Toronto club, the Canadian leader in professional golf, and Percy Barrett of Lambton, who ran third in the United States national this year, have challenged [Willie] Anderson, the American champion, and Alexander Smith, former American champion, to a series of games…. It would practically decide the international championship” (7 December 1905, p. 1). In January of 1906, Cumming and Barrett were scheduled to travel together by train from New York City to Mexico City for a series of big international golf tournaments there , but Cumming missed the train and withdrew from the tournaments. But they travelled together in the summer: they were the Toronto representatives at the U.S. Open in Chicago in 1906. If Rickwood had come to Toronto to meet up with Barrett in 1905 or 1906, he would almost inevitably have also met Cumming.

In Toronto over the next few years, we find evidence of Fred Rickwood recorded in The Toronto City Directory 1907 (by Might Directories): “Rickwood, Frederick, lab b 1569 Queen e.” The abbreviations in the directory indicate that the person at the address in question was a labourer boarding in a home on Queen Street, East.

But what of the name “Frederick”?

It is important to acknowledge that Fred Rickwood’s parents did not officially name him “Frederick.” He was christened as Fred, and his name almost invariably appears in official records in Britain and Canada as Fred.

Note, however, that in the 1921 Canadian census, he appears as Frederick. On the day of the taking of the census, however, he and his family seem not to have been at home at the Summit Golf and Country Club where they then lived. The information in the census about this family is garbled. The mixture of accurate and inaccurate information about them seems to have been offered to the census taker by the other employees in residence at the golf club who worked under Rickwood. They gave out Fred’s name as Frederick, and they also misnamed his wife and one of his children! But they got other names right.

My explanation of this misnaming is that people tend to assume that a person called “Fred” is probably officially named “Frederick.” There are very few “Freds” in the world who are not also “Fredericks.” I suggest that we see that assumption at play in the minds of the employees talking about him to the 1921 census taker, and I suspect that we see that assumption at play in the mind of the boarding home ownerin Rickwood’s East Toronto neighbourhood who gave out his boarder’s name as “Frederick” for the Toronto City Directory. Either the owner of the home assumed that “Fred” was short for “Frederick,” or the person recording names for the Directory did. The clerk who recorded his marriage to Edith Barrett in 1909 did something similar, adding an underlined “K” to the name “Fred”: “Fred.K.” And his own daughter-in-law told the Ilkley Gazette in 1968 that his name was “Frederick Rickwood” (cited by Jim Seton, “Across the Years,” Ilkley Gazette, 18 January 2018).

The listing in the 1908 Directory is more interesting than the 1907 listing: “Rickwood, Frederick gdnr 61 Swanwick Ave.”

It is intriguing to see that “Frederick” Rickwood is now a gardener. Recall that Fred Rickwood’s father was a gardener, and that Harry Vardon’s father was called a “gardener” even though he was what we would call the “greenkeeper” for the golf course on Jersey where he worked.

Even the great Canadian golf architect Stanley Thompson was originally described as a “gardener.” When Canadian Golfer published an article on the formation of the new firm Thompson, Cumming & Thompson in 1920, we read that “Stanley Thompson’s specialty will be landscape gardening, he having taken courses in this interesting profession” (February 1920, vol v no 10, p. 614). Thompson also described himself as a “landscape engineer,” indicating that one of his specialties was “course beautifying.”

So we can see that when golf in Canada was in its infancy in the early 1900s, there were not yet recognized names for various golf industry workers, and so a golf course employee might well have indicated to census takers or the compilers of city directories that he was a “gardener,” even if he was actually helping to build and maintain golf courses.

Such is my suspicion regarding “Frederick” Rickwood, the “gardener”: he was actually Fred Rickwood, the greenkeeper and construction man.

From this point of view, an interesting thing about both “Frederick” Rickwood’s 1907 address (1569 Queen Street, East) and his 1908 address (61 Swanwick Avenue) is that Rickwood was never living more than about one mile from the clubhouse of the Toronto Golf Club (where Edith Barrett lived as of 1908). I suspect that he was actually working at the Toronto Golf Club, perhaps as a member of the greenkeeping staff, and perhaps also helping the club’s professional golfer build golf courses in Toronto and in other communities across southern and eastern Ontario.

The head professional golfer at the Toronto Golf Club was George Cumming, known ever since as the “doyen” of Canadian golf professionals, for he trained as apprentices a majority of the first generation of golf professionals who would subsequently fan out across golf courses from coast to coast in Canada during the first third of the twentieth century, becoming the primary agents in the establishment of golf as a game in Canada.

This process of establishing golf as a Canadian sport was gathering momentum during the three years that Rickwood was in Toronto, and Cumming was the prime mover in this process. Not only did Cumming win the Canadian Open in 1905, but three of his apprentices who had graduated to become head professionals at the clubs that became Royal Quebec, Royal Montreal, and Royal Ottawa (Albert Murray, Charles Murray, and Karl Keffer, respectively) won six of the next nine championships (the Murray brothers and Keffer each won the championship twice).

In recognition of his role as progenitor of at least thirty golf professionals from his pro shop at the Toronto Golf Club between 1900 and 1950, another name given to Cumming was “Daddy of them all” (Canadian Golfer, October 1919, vol 5 no 6, p. 341).

When he won the Toronto and District Professional Championship in 1919 by five strokes, vanquishing very accomplished former apprentices while doing so, Canadian Golfer wrote: “George Cumming’s victory was a particularly popular one. He has done much for golf in Canada, having trained Karl Keffer, C.R. Murray, A.H. Murray, Nicol Thompson, W.M. Freeman, Frank Freeman, and the majority of the younger pros in Canada. He and his pupils have won the Open Championship of Canada no fewer than seven times and been runner-up on six occasions – certainly a most unique record” (October 1919, vol 5 no 6, pp. 341-42).

Living about half a mile from “Frederick” Rickwood, and about the same distance from the Toronto Golf Club golf course, were two of these apprentices of George Cumming: Frank and William Freeman. Rickwood developed a close relationship with them.

When Fred Rickwood returned from Europe in 1919 after World War I, William Freeman would give him a few months of work in his golf shop at Lambton while Rickwood sought his own position at a golf club in Toronto for 1920.

It was not just Rickwood and Willie Freeman who were good friends, however, for all of Cumming’s apprentices in the 1900 to 1914 period were very close. Karl Keffer, for instance, married one of the Freeman brother’s sisters, Evelyn. The best man at Keffer’s wedding was another of Cumming’s apprentices, William (“Billy”) Bell. And Keffer himself was the best man at the wedding of Fred Rickwood and Edith Barrett.

Many of Cumming’s apprentices – all of them Rickwood’s friends – posed with their mentor at the 1912 Canadian Open, as seen below.

Figure 21 From left: Charles Murray, William "Billy" Bell, Frank Freeman, Karl Keffer, Albert Murray, Willie Freeman, all former apprentices of George Cumming, on right, at 1912 Canadian Open.

By at least 1908, however, Rickwood was working not so much as a “gardener” at the Toronto Golf Club, but rather as another of the many apprentices under the supervision of George Cumming. We read in the Quebec Chronicle in 1909 that “Rickwood is a pupil of the celebrated Toronto professional, J. [sic] Cumming, and holds strong recommendations from him” (15 May 1909, p. 6).

The word “pupil” was used in those days to indicate that an assistant professional was an “apprentice” of a head professional.

The fact that Rickwood had become one of Cumming’s apprentices suggests how Rickwood came to be offered a position at Amherst Golf Club when the golf enthusiasts in that town decided to found a golf club and then build a golf course in 1908.

As the head professional at the Toronto Golf Club, George Cumming was regarded as the most important golf professional in Canada. From across Canada, he was approached by all sorts of established golf clubs, and by all sorts of groups and individuals looking to found golf clubs, for advice about golf course location and construction and for recommendations regarding golf professionals available for hire. So, Cumming would have had his finger on the pulse of virtually all golfing activity in Canada in 1908 and might well have been the one who recommended Rickwood to the people in Amherst.

Cumming was just as much a golf course architect as a head professional at Toronto Golf Club. He went about Ontario all the while he was head pro at the Toronto Golf Club (from 1900 to 1950) building dozens of golf courses, and he often took one or another of his apprentices along with him to teach them this aspect of the golf professional’s craft. “Gardener” and “Labourer” “Frederick” Rickwood may have gathered his first North American golf course construction experience in this way, for Cumming was quite active in laying out golf courses during the period that Rickwood was his “pupil.”

And so Cumming would have been able to recommend to Amherst Golf Club just what the people there needed: a golf professional who could build them a golf course, build them the equipment needed to play the game, and teach them how to swing a golf club.

Cumming, for instance, must have been instrumental in recommending his 18-year-old former assistant professional Albert Murray to Quebec Golf Club in 1905 to build a new nine-hole golf course for this long-established golf club. The following year, Quebec Golf Club hired Murray as its first professional golfer. When Murray later left for Outremont Golf Club in Montreal at the end of the 1908 season, he continued to advise Quebec Golf Club during its attempt to replace him.

The replacement golf professional would be Fred Rickwood, who left Amherst Golf Club in 1909 to become the second ever golf professional at Quebec Golf Club. This was probably a case of one Cumming associate helping another.

Figure 22 From left to right, Karl Keffer, Albert Murray, and Fred Rickwood. The three men are probably at a Canadian Open before World War I. A photograph from the Canadian Golf Hall of Fame, provided by Ian Murray.

But this is to get ahead of our story, for Rickwood’s service as the professional golfer at the Quebec Golf Club was bracketed by two stints as the professional golfer for the Amherst Golf Club. In 1908-09, he built Amherst’s first golf course. And a few years later he returned from Quebec to build Amherst a second golf course!

Amherst

In Amherst in 1908, three of the women leaders of the wealthier members of Amherst society – Mrs. McDougal, Mrs. Hickman, and Mrs. Hodgeson – decided that it would be a good thing for Amherst to have a golf club. Golf was said to provide good physical and mental exercise for the professional classes. So these three women canvassed their wealthy friends for the funds needed to start a golf club and build a golf course. Their industry matched their ambition, and so within a few weeks Amherst had its first golf club.

Next came the matter of a golf course: where to build it, and who to build it?

There were only about two dozen professional golfers in all of Canada in 1908 and somehow these good ladies got hold of one: Fred Rickwood.